Neverending Horror

The Burnt Offering is where Stu Horvath thinks too much in public so he can live a quieter life in private.

———

Editor’s Note: This story has been reprinted from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Nineteen. Want to check it out in all its wonderfully-laid-out glory? Pick up this issue or subscribe today!

———

You’re up later than usual. It is one of those nights you don’t want to sleep, but you don’t want to do anything in particular, either. The TV is off, you can’t think of any music to listen to. You wind up spending an hour just wandering your place, looking at things and enjoying the silence.

Except, the silence feels oppressive. Without a particular sound to focus on, you are listening hard to everything, waiting for the slightest noise. When it comes – that creak, that sigh of floorboards, that patter on a windowpane – your heart races and horripilation dances across your skin.

You wonder if you locked the front door. You wonder if that book on the table next to you will work as an improvised weapon. Your mind races through a million rational explanations, perhaps you even force yourself to laugh dismissively to yourself. You’re being silly. You know that. But you’re still afraid.

This heightened state of awareness is the goal of horror. Only when the sharp edge of panic subverts our everyday feelings of comfort and safety can horror do its work.

While it is easy for a noise in the night to give you the heebie-jeebies, there are hurdles that prevent you from fully experiencing those delicious negative emotions when you read a horror story or watch a horror movie. For a book, it is the act of turning the page. For movies, a myriad of ambient audio and visual distractions conspire for your attention. These subtle physical realities constantly remind you that the horror isn’t real – you’re safe in your home, not being pursued across a field by a chainsaw-wielding lunatic.

Sometimes, the real world and the story fall into synch. The night is dark enough, the thunder loud enough and your mind focused enough to cross over into an altered, trance-like state. Here, you suspend your disbelief so far that it overcomes the physical sensations that keep you grounded. You enter a mental space where frights quicken your pulse and linger in your dreams for days. Those are rare, treasured moments.

And yet, you are still merely an observer. Much horror depends on empathy – you identify with a character and take on a measure of their suffering. Our inability to warn them of danger or save them from death may make us feel helpless, which in turn allows us to feel frightened, but in the end, horror is something that happens to other people.

In theory, this is not true of videogames. The player, whose agency is necessary for the story to progress, is present within the story in a way completely different from books or movies. The story is less about a fictional character and more about your own choices and actions. By exerting control over the game, you weaken the membrane separating yourself from the character whose role you inhabit, making your brain less effective at reminding you that this is all fantasy. It allows you to feel unsafe in the comfort of your home.

There is no James Sunderland in Silent Hill 2. There is no Leon Kennedy in Resident Evil 4. In Dead Space, the narrative may say that necromorphs are stalking Isaac Clarke aboard the Ishimura, but it doesn’t feel that way to the player. It is you, cautiously making your way down the deserted corridors, plasma cutter at the ready. Clarke is your puppet – without your input, he just stands there. You are the ghost in the machine.

For the first hour or two, Dead Space (or Silent Hill 2, or Resident Evil 4) is the scariest thing you’ve ever played, but that eventually begins to erode. Games are inherently all about you. You set the pace and do so at a remove. If something bad happens to your character, it doesn’t affect you – it is like dropping a toy in the garbage disposal. You feel no pain. You certainly don’t come anywhere near death. In a game, you get all of the power with none of the responsibility.

Power is the antithesis of horror, but it is impossible to craft an experience lasting dozens of hours around helplessness. And so you fight, you improve and you win. By the end, it may still be scary, it may even have an unhappy ending, but it is no longer horror. It is just another action adventure game wearing a Halloween mask.

There are exceptions. Amnesia: The Dark Descent, for example, is the rare game that makes a player feel powerless at every turn. There are no weapons in Amnesia and every encounter with a creature ends in your death. The only way to survive is to hide and hope.

Despite the success of Stephen King’s novels, horror is purest in short form, as Poe and Lovecraft attest. While Eternal Darkness: Sanity’s Requiem is a long game, it involves a cast of a dozen playable characters spread across the world through different eras of history. As such, it functions as a kind of anthology, never settling into one thing for very long and, thanks to the game’s sanity mechanic, constantly subverting your perception of reality. As characters become mentally debilitated by the terrors they experience, the player is beset by strange sounds, graphical glitches and horrific death hallucinations.

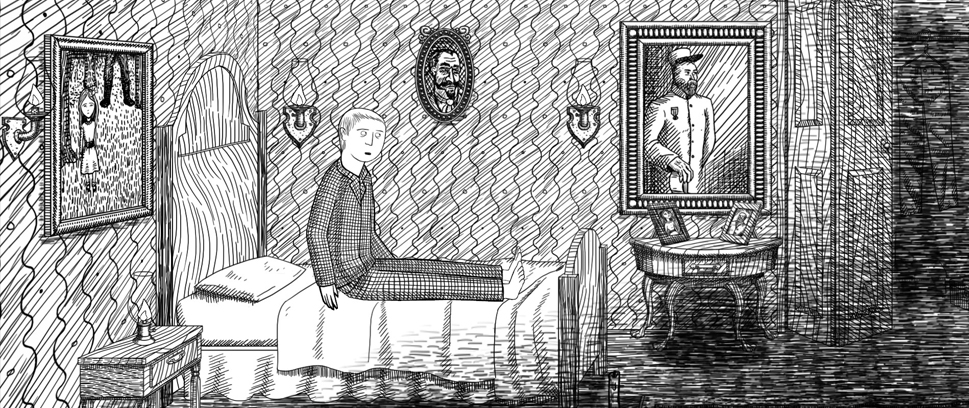

Recently, Infinitap Games released Neverending Nightmares, a side-scrolling adventure game in the style of the macabre illustrations of Edward Gorey. Like Amnesia, the protagonist, Thomas, is helpless. He wanders environments from mental hospitals to rambling woods barefoot, dressed only in pajamas. If he runs too long, he doubles over into an asthmatic wheeze, unable to continue until he catches his breath. Like Eternal Darkness, it is constantly changing. Each time Thomas dies or witnesses something truly traumatic, he awakens again in his bed. From there, he has no choice but to explore until something terrifying happens, and he awakens again. And again. And again.

And, perhaps best of all, there isn’t always something happening in Neverending Nightmares. Thomas walks down seemingly endless hallways without anything supernatural occurring. The chilling soundscape wraps around you, constantly threatening some new fright, but they only occur sparingly, when they are most effective. The rest of the time, the game is content to let you squirm waiting for them.

That patience is what makes me think there is hope for horror in videogames. Neverending Nightmares understands that horror is in flashing fangs or splattered blood – it is in the quiet moments, in the dark, wondering if you just heard something move behind you, wondering if it was just a trick of the light, wondering if you’re as alone as you had thought.

———

Follow Stu Horvath on Twitter @StuHorvath.