Powers of Darkness

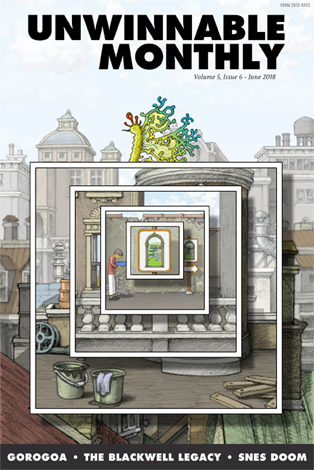

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #104. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #104. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

The Burnt Offering is where Stu Horvath thinks too much in public so he can live a quieter life in private.

———

Of all the night creatures, the vampire has fixed for itself a prominent place in our popular imagination.

And why not? It is immortal, a condition fit for human envy. It is inhumanly strong, can exert its influence through its gaze and can slip into the form of a wolf or bat or vapor as it wishes. It walks among us – alike, but oh, so different; flawed, but inarguably superior; an apex predator. Though ripe for use as a metaphor for countless afflictions – physical, psychological or spiritual – the vampire is also a power fantasy, despite the legendary costs of being one. Perhaps even because of them. The aversion to daylight and religion sets a certain romantic mood and the sexual underpinning of the creature’s bloodlust is no doubt a turn-on for some.

Over the centuries, no small amount of thought has gone into the vampire’s relationship between its power and its humanity (John Polidori’s “The Vampyre,” from 1819, is often considered the birth of the literary vampire, but the folklore winds back much farther). The consensus is that, as the vampire grows in power, its humanity diminishes. There is also a widely held modern notion that the older a vampire gets, the more powerful, and therefore monstrous, it is: its humanity shed long ago, as if a snake’s skin.

If this is true, then what of the fledgling vampire? If the ancients are abominations, it stands to reason that a vampire freshly born after three days in its earthy womb would bear little resemblance to the myriad of Draculas that stalk the shadows of our fancy.

The newborn vampire is the subject of DontNod’s game Vampyr. In it, players take the role of Jonathan Reid, a surgeon (specializing in blood transfusion research, naturally) recently returned to London from the trenches of the Great War. There, in a city rampaged by the Spanish flu, Reid is attacked, and turned, by a vampire.

His undead condition puts him at odds with his Hippocratic Oath, a quandary directly reflected by the game’s mechanics. To gain experience – and more powerful vampiric abilities – Reid must feed on the innocent people of London, the same people he tends to as a doctor. The more time he invests in a patient, represented by conversations, quests and the occasional administration of medicine, the more experience Reid reaps in his bloody harvest – if the player chooses to succumb. If he embraces too many people, he sends the city into chaos.

For the most part, Vampyr measures power in Reid’s physical fighting prowess – the less experience he has, the more limited he is in combat with the vampire hunters and mutated thralls who clutter the quarantine zones connecting London’s neighborhoods. Clinging to his humanity leaves him frail. My Reid is neither strong nor graceful. Worse, there is no way to avoid combat. Early in the game, Reid swears that he will take no more lives, but his actions make it clear that the good doctor only meant certain lives.

As a vampire, Reid never suffers from his thirst. Aside from taking a beating in the street fights, there is no meaningful consequence for his fasting. Starving dogs turn feral, but if a vampire has a similarly debilitating need for blood, Reid never shows it. Without that need, there is no calculus between power and humanity.

[pullquote]Without that need, there is no calculus between power and humanity.[/pullquote]

The vampire is a slave to its thirst. It must drink, but it must also remain undetected so that it may drink again. Many of the creature’s supernatural abilities – mesmerism, shapeshifting – function in the service of remaining undetected. A creature of guile, it’s power is measured in its ability to manipulate the herd of humanity it preys on.

Secret addicts can remain undetected their entire lives. Vampires are addicts of blood. The tension between power and humanity in a vampire is an illusion: There is only thirst and its quenching. In giving the players the choice to feed, in not creating some mechanism of compulsion beyond the player’s control, Vampyr misunderstands the vampire. The creature at the heart of the game is a monster of an entirely different sort, a man of means, station and position who can indulge his desires without fear of consequence. A vampire, true, but one that is all too human.

———

Stu Horvath is the editor in chief of Unwinnable. He reads a lot, drinks whiskey and spends his free time calling up demons. Follow him on Twitter @StuHorvath.