Mythology of the Commons

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #163. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Analyzing the digital and analog feedback loop.

———

Contains spoilers for the ending of Folklore

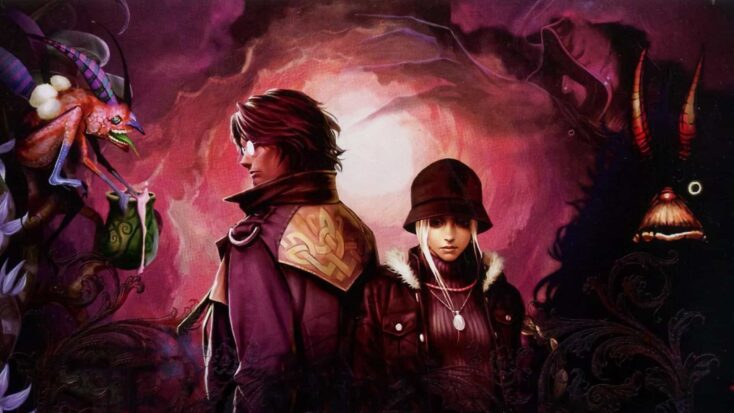

Anyone who’s been around me long enough in games writing or design jams knows that one of my favorite titles of all time is Folklore. The game is a somewhat obscure action RPG for the PS3 developed by the now-defunct studio, Game Republic (also known for the Genji series, some Dragonball DS titles, and Majin and the Forsaken Kingdom). The game was known for its gorgeous graphics, which one observant blogger claims (although frustratingly without reference) were heavily inspired by artists like Patrick Woodroffe and Roger Dean. As well, the game was accompanied by a haunting soundtrack featuring none other than Kenji Kawai, of Ghost in the Shell fame. Folklore was also known for being one of the only games that made use of the SIXAXIS motion-sensor in the PS3 controller, making its combat rhythmic in nature.

The brief synopsis is a woman named Ellen, a university student, returns to her Irish home village Doolin, known as the place where the living can meet the dead. Ellen’s narrative arc is strangely similar to that of the protagonists of early Silent Hill games, she is contacted by her mother (previously believed deceased) who tells her to meet her in Doolin. While the quaint yet gloomy atmosphere of this village is a far cry from the purgatorial malaise of Silent Hill, Doolin is plagued by murders and also possesses a gateway to a Netherworld – but this one leads to several spectral faerie realms.

This game encapsulates a lot of narrative themes, movements and aesthetics that are pervasive throughout my creative life. Including (but not limited to): interconnection in communities (both local and global), the unreliability of memory (both personal and cultural), spirituality, fantasy art and literature, and Gothic literature. Folklore is a game that I have wanted remastered perhaps more than Legend of Dragoon or the Suikoden series (though I am quite excited about the forthcoming remasters of the latter). It’s a very personal title for me.

I grew up on the west coast of Canada on a small island where neo-pagan and hippie subcultures abounded and were nestled amongst forests. As one might imagine, this instilled a strong connection to nature in me, although I didn’t strictly follow any of the former subcultures. This coastline did, however, introduce me to faerie subculture, perhaps one of the geekiest I’m proudly still a part of in some regard (happy Black Fae Day to those who celebrate, by the way). But specifically, the ominous side of it. The side that acknowledges that faeries, or similar such spirits and their realms around the world, are not just sanitized, Day-Glo and glitter entities. The side that characterizes the fae as dangerously volatile signifiers of nature versus the humans and the anthropocene.

I was drawn to the fae as they were represented in works by authors like Patricia A. McKillip, Charles de Lint, O.R. Melling and Neil Gaiman. Creatures as described by these authors often stole souls or spilled as much blood as vampires or other more recognized monsters did. Often even when lines were drawn between morally upright and fallen fae, they were hazy mirage-like lines these beings crisscrossed constantly in their capriciousness. Fae logic (if you can call it that) is also just as unreliable.

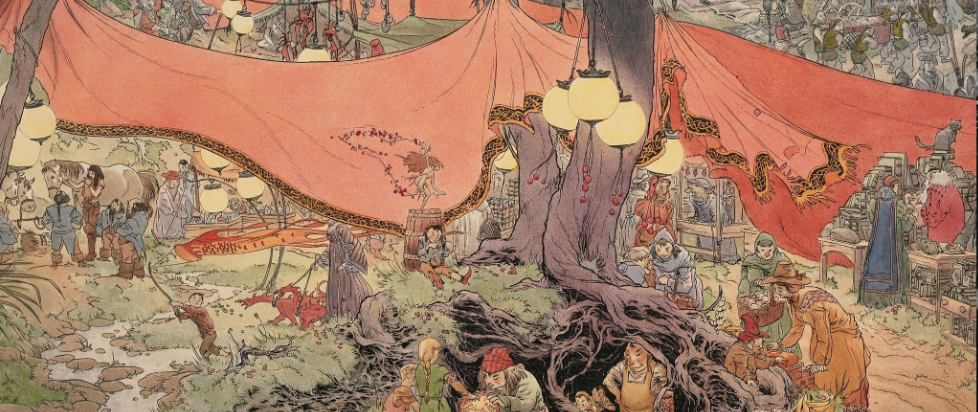

On the visual side, the lightest I would go regarding faerie art would be Amy Brown, with my perennial favorites being Charles Vess, Alan Lee, Arthur Rackham, Sulamith Wulfing, Brian Froud and above all Kinuko Y. Craft (also known as K.Y. Craft). That my favorite authors and artists often went hand-in-hand was a wonderful bonus; K.Y. Craft painted gorgeous covers for Patricia A. McKillip’s early noughties work, Neil Gaiman often collaborated with Charles Vess and some of my favorite films growing up such as Labyrinth and Dark Crystal owed their art direction to Brian Froud. Or they heavily influenced films like Legend or Pan’s Labryinth, which carry a similar tone to Folklore, a game that is mainly about faeries and their Netherworld signifying the ephemerality of human lives and the permeability of reality, memory and myth. Broadly, Folklore is a game that tells a story about how myths proliferate and make up the fabric of human existence.

Myth is something that over time I have found more compelling than fantasy, perhaps because fantasy would not exist without it. A lot of myths are ur-texts for the stories we tell today in our multimedia. Myth is also, as semiologist Roland Barthes once explained, a type of speech which promotes discourse. Yes, I know discourse is a fraught word these days, especially in games criticism. But discourse is something that, despite how much trouble it can cause in some instances, we hope our artistic creations inspire. As Barthes put it, since myth is a type of speech that is imbued with significance by human history, everything (whether visual, textual or otherwise) has the potential to become myth. This is why urban myths, also sometimes called urban legends, can originate from anywhere and transmit cultural values or concerns.

As a related term, folklore can be thought of as the means by which myths get perpetuated. The term refers to the traditional beliefs and customs, often passed down orally by common people. And as well, since folklore is often of the common people, these beliefs and customs are prosaic ones, such as issues of identity, morality and interpersonal politics, to name just a few. And the writers of Folklore communicated this well via their narrative design. Half of the gameplay is Ellen and her ally Keats, an enigmatic writer for a local Doolin Occult magazine learning about the history of the village and how it might tie back to the supernatural murderer at large and Ellen’s past. Some villagers are superstitious of the fae, others are staunchly rationalist. But whether or not they believe in a material supernatural entity or realm, they are affected by the mysterious murders nonetheless. Keats first line in the game encapsulates how even in the post-Enlightenment age, there is a complicated relationship between science and spirituality:

“Even in modern times, many phenomena go unexplained. Spiritual encounters are constantly reported in all corners of the globe. At the same time, the march of modern science makes a steady advance. It may not be long before the boundaries between life and death, indeed, the destinies of men . . . will be dissected and explained to us by modern science.”

Keats himself is mythical. His character is revealed near the end of the game to be a fae construct, created by the Netherworld to protect Ellen. He is suggested by the game’s plot to be an adult form of a boy named Herve that Ellen knew as a child. Cecilia wanted to grow up to be a painter and Herve wanted to be a writer. But Herve was very sickly and Ellen (then called Cecilia) prayed during Samhain underneath the Henge in Doolin for his health and met a Netherworld creature that told her they could save Herve if she spilled her blood. This led to a medical crisis which concluded with Herve convincing the village doctor to end his life in order to save Cecilia’s. Cecilia’s mother changed her child’s name to Ellen and gave her up for adoption, to protect her from the enraged villagers who suspected Cecilia was the cause of Herve’s death. In one of the final scenes of the game, while Ellen is visiting Keats’ office, she comments that the location is a part of the Netherworld and Keats comes across an old drawing that depicts Cecilia as she was next to what looks like himself (or what Cecilia pictured Herve would look like if he grew up to be a writer). And of course, there’s the obvious reference with Keats’ name being that of a famous writer who died early in his life.

This ghost story at the core of this game is uniquely EcoGothic in some ways. EcoGothic is a relatively new school of thought that brings together Ecocriticism, which analyzes nature in its literary form and often from a non-anthropocentric perspective, and the Gothic aspects of nature particularly with regard to monstrous, non-human, trans-human, post-human or hybrid bodies. Swamp Thing, especially the 2021-2022 run of the series by Ram V, is quintessentially EcoGothic. This run put a heavy emphasis on the mythical constructions of natural and industrial processes and how bodies are transformed or subsumed by either paradigm of progress. Just as Levi Kamei and his brother Jacob become vegetal and animalistic avatars of the Green world, Harper Pilgrim becomes the avatar of industrial machines, known as the Parliament of Gears. As the Kamei brothers are originally from an Indian community that revered the Green, there’s also a post-colonial element to the clash between Eastern and Western paradigms of progress as well. The EcoGothic accounts for how binaries and the liminal spaces between them comment on the complexity of the anthropocene and how we often perceive nature as a symbolic and separate force rather than an intricately organic and symbiotic one.

While there isn’t necessarily an overtly intersectional EcoGothic tone to Folklore, it does deal with bodies irrevocably changed by nature, binaries and transformed bodies. Keats, Herve and Ellen/Cecilia inhabit bodies that have been spiritually and viscerally affected by the fae. Yes, the fae in this game are more phantoms than they are your usual pixies and the like, but they and their realms are still deeply representative of the natural world. Those worlds are binary even in design, with Doolin purposefully portrayed in drab shades and hues, while even the most infernal of faerie realms such as HellRealm are awash in saturated jewel tones. Doolin also contains liminal spaces like the Henge’s gateway to the Netherworld and Keats’ office. Even the gameplay is binary, alternating every chapter between Ellen’s perspective and Keats’.

There’s a lot of potential in the EcoGothic and faerie mythology to offer unique narrative design. From Software understood this with its VR title Déraciné, which put players in the role of a faerie. I might return to this next column as I feel there are a lot of missed opportunities in games to portray faerie lore. Inflexion Games’ upcoming survival MMO Nightingale is promising, but not exactly what I have in mind. So far, Folklore stands alone as a game that touches on how dark fantasy doesn’t always have to resemble a medieval romance and can be quite relevant to our current zeitgeist. Folklore is to Gothic games what Midsommar was to horror movies, in my opinion, and it’s a shame that Game Republic never got that sequel they hoped for.

———

Phoenix Simms is a writer and indie narrative designer from Atlantic Canada. You can lure her out of hibernation during the winter with rare McKillip novels, Japanese stationery goods, and ornate cupcakes.