The Hopeful Disharmony of Into the Doomed World

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #154. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Analyzing the digital and analog feedback loop.

———

We are often prone to characterizing hope as a cloying and intangible virtue, especially during times such as these. Hope (for me at least) is not a rosy concept, nor is it synonymous with optimism or nostalgia. On that last point, I have previously explored how even nostalgia can be pragmatic and distilled from feelings of disappointment. Feelings that are intense enough to galvanize us to enact positive change in the present. Hope is a similar driving force or state of being, one that’s bittersweet because you persist with it in the face of inevitable or unconscionable facts. This is the kind of hopeful tone that Javy Gwaltney’s new short-story collection, Into the Doomed World (ITDW), gives not just a voice but a chorus to. I reached out to the creator of the acclaimed The Terror Aboard the Speedwell about his new short-story collection about 30 self-aware NPCs in a world that’s been sentenced to a slow apocalypse by its player to find out what inspired him to write it.

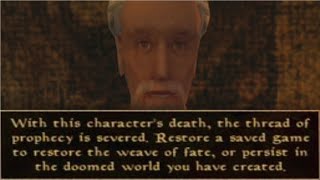

Gwaltney cites two guiding inspirations for his collection, one literary and one ludic. The former is Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology, which Gwaltney describes as: “a series of free verse poems that collectively tell a story about a fictional small town in Illinois. Essentially, it’s a choir of dead voices confessing the gossip, the pain, despair and even small moments of joy in a community. It’s beautifully written and, as someone who’s always favored introspective stories about quiet suffering over grand sweeping dramas or epics, I found it to be one of the primary guiding forces for how to write this collection, though stylistically they’re very different.” The latter is The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind which “made it possible for you to kill essential quest-giving NPCs. Whenever you did that, you received the following message:

With this character’s death, the thread of prophecy is severed. Restore a saved game to restore the weave of fate, or persist in the doomed world you have created.

So, though the player had failed the quest, they were allowed to remain in the world they had damned alongside the countless little digital people they had damned with it.” Gwaltney was fascinated by this concept because it was clearly relevant to the current zeitgeist we’re contending with. In fact, this collection has been a way to grapple with his fears, many of which we all share of ongoing climate change ignorance and the rolling back of human rights (as we have seen with the overturning of Roe V. Wade last month).

Realizing the ineffectual and complicit nature of many figureheads in power, Into the Doomed World explores how the structural failures we experience in societies point to another important realization about collective action: “To me the story collection is about grappling with the sort of realization that we’re on our own. There’s no cosmic or structural safeguard that’s going to save us. We only have each other. And a lot of people do a lot of things with that realization and that sort of response, the variety and breadth of it, is what I wanted to explore in these stories.”

In recent years the number of meta-narratives about games, their systems and what they can represent has been growing. From Kieron Gillen’s Die project (via a comic series and a tabletop game), which navigates the dark side of escapism and how it estranges us from real-world concerns, to games like Kentucky Route Zero, NORCO and Citizen Sleeper that concern themselves with late Capitalist dissolution of environments, communities, human rights and bodies, it’s safe to say that games and games criticism is well aware of civilization’s current and ongoing crises.

Recent game criticism has become more vocal about gaming’s role in politics and global impact as well as how games are not the answer to our structural woes. We have also seen how games are often falsely conflated with activism and empowerment, when in truth they are often tools of imperial or colonialist-capitalist design, as Meghna Jayanth delineated in her Digital Games Research Association keynote last year. Arguably, the player in Into the Doomed World, Eric the Righteous, could be a prime example of the “model player” or “white protagonist” who’s pleasure is to make decisions on behalf of every other inhabitant in the world. It’ll be interesting to see how Eric’s role in this narrative about a global community is deconstructed via the 30 NPCs viewpoints. Making the NPCs self-aware and central to the collection also humanizes those who are usually dehumanized in heroic game narratives.

If you’re familiar with Gwaltney’s work, you know that he has a knack for portraying characters and scenarios that effortlessly mix bleak outlooks with undercurrents of hope and humor despite the odds. The banter-filled interactions between Meat, Nick, and potentially your chosen protagonist in Speedwell are exemplar of this. What helps them triumph, if they triumph by a knife’s edge in some playthroughs, is leaning more towards humane and cooperative options. Gwaltney’s player is swiftly and severely impacted by choices taken that are authoritarian or “lone savior”-esque, like when the protagonist is given the choice to euthanize an infected crew member before knowing their fate is certain. Gwaltney agrees with Jayanth’s model of the colonialist-capitalist protagonist, especially given that he’s stated that “a huge part of what the collection is about is power dynamics and the question of saviors” and whether such saviors are real or reliable.

I hesitate to call this collection hopepunk, although that genre and movement emphasizes similar aspects of resistance and life-affirmation in the face of bleak truths, as well as the importance of caring for a community. At once, ITDW actively rejects categories like Doomer Lit (rather self-explanatory) or Grimdark fantasy (read: Soulsborne). Gwaltney’s aim is to offer a nuanced take on apocalyptic fiction that pushes back against properties like The Walking Dead (especially the TV adaptation) which has amounted to little more than misery porn over the years. “I know some people love that sort of thing but I just don’t have the stomach for it – the perpetual eternity of it, I mean. That kind of despair is very boring to me” he says.

“With ITDW, I tried to write varied stories of the many responses that people could have to society crumbling around them. Those who have been oppressed or slighted by that societal structure would likely find joy instead of despair, for example. While another might mourn it. Another might observe it dispassionately because they’re privileged enough to do so.”

But it’s important to keep in mind that despite the epic fantasy framing of ITDW, the collection is not a fantasy epic. “Now, there are fantasy epic events and tropes happening – prophecies, chosen ones, obscure and dangerous magical arts – but those are mostly used as props to explore what these people are going through on an intellectual and emotional level,” Gwaltney emphasizes.

Some other significant influences for Gwaltney’s multi-faceted exploration of power and living in a disastrous era are literary writers like James Joyce, William Faulkner, Raymond Carver, Giovanni Bocaccio and Geoffrey Chaucer. The idea for having 30 voices came specifically from Bocaccio’s book about weathering the Black Plague. Gwaltney originally aimed to be a 1:1 ratio with Bocaccio’s 100 viewpoints, but after workshopping found that quality over quantity was the best strategy. As he explains: “I love every single character and story in this collection as is. And taken as a whole, I think the spread here gives access to characters who hopefully feel substantially different from one another in terms of how they perceive, react, and exist to the world they inhabit.” I feel this was a fortuitous choice, as not only did the resulting 30-character cast end up being nearly 1:1 with Chaucer, 30 characters make for a similar number to a Greek chorus for an epic play. Throughout time such choruses numbered anywhere from 1 to 50 people, and Masters’ work on Spoon River Anthology also drew from this storytelling device in similar manner; allowing for both individualized voices within a recognized collective. Such narratives capture the nuanced disharmony of a community.

What I love about all these influences mentioned above is that it just goes to show that some writers and narrative designers are not just working within a siloed canon of games storytelling, they’re working within broader, interconnected canons of storytelling as well. Modern literary writers and poets are more frequently drawing on the language of play and game systems to get at the 21st-century experience. Hannah Nicklin noted similar insights in her 2020 GDC talk on how drawing from ensemble narratives and interdisciplinary arts like theatre helped create Gutefabrik’s award-winning game Mutazione, which also decenters the hero in favor of empowering a communal perspective. Games are commonplace enough now that the discourse is not as opaque and specialized as it was before.

Narratives that center on the collective don’t let us off easy with regards to our individual responsibility to know and care for each other and our plural, interconnected realities. Into the Doomed World aptly gets at how life in the social media age is a complex navigation of being an individual that pivots between micro and macro perspectives. It focuses on the beauty of recognizing the disharmony within a community and how we can work together to reconcile it during times of crisis.

“I will say that when I write I tend to lean in the direction of hope even when the circumstances suggest that it’s a foolish notion,” Gwaltney states. “I have no idea if it’s [the collection] going to work as well as I want it to, but I’d rather create interesting failures rather than competent and safe successes.”

———

Phoenix Simms is a writer and indie narrative designer from Atlantic Canada. You can lure her out of hibernation during the winter with rare McKillip novels, Japanese stationery goods, and ornate cupcakes.