Misremembering DOOM

This is an excerpt from the cover story of Unwinnable Monthly #153. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Id Software turned heads when the company announced they were porting DOOM (2016) to the Nintendo Switch. Fans and critics were immediately curious, yet skeptical. The fast-paced reboot of the influential first-person shooter series was a case study in technical excellence on the PC, PlayStation 4 and Xbox One. Squeezing it down onto a 13.4GB download (plus a 9 GB multiplayer patch) would be challenging on portable hardware, but the prospect was intriguing. Sure enough, critical consensus declared it an admirable effort, retaining the core gameplay and spirit of the series, if not its graphical fidelity and smooth 60 frames per second.

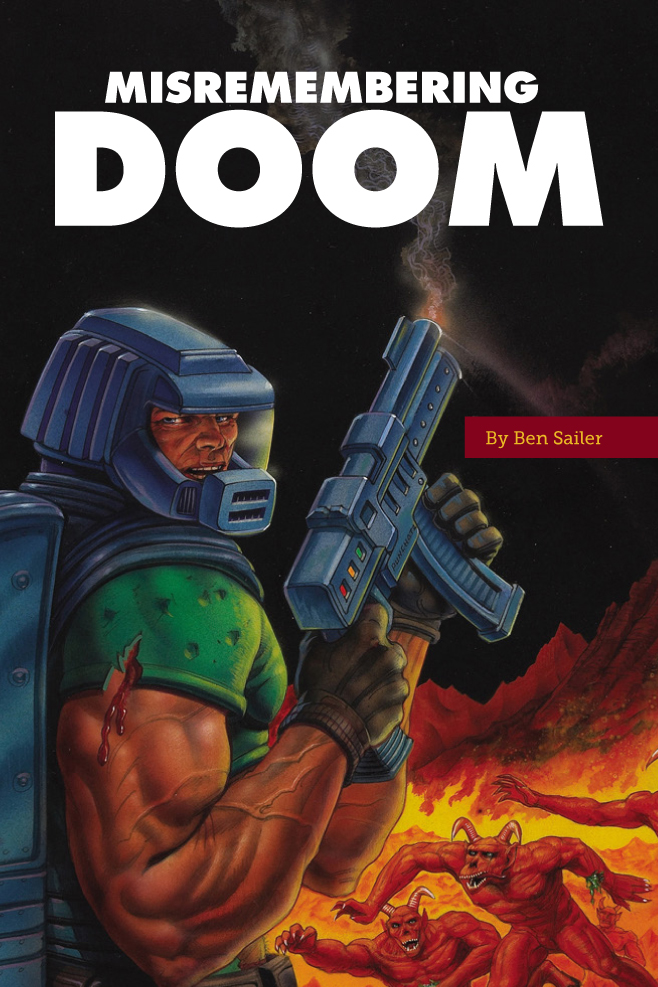

While it’s an impressive accomplishment, it’s somehow not the most improbable port of the long-running demon-blasting franchise to appear on an underpowered Nintendo console. That honor belongs to the Super Nintendo version of the debut Doom. Released by Williams Entertainment on Sept. 1, 1995, it crammed 22 levels from the PC original onto a blood-red 128Mbit cartridge, an incredible feat made possible by innovative technical trickery (and possibly a deal with devil). It’s also arguably the worst version of the game, possibly the worst entry in the series overall, and my favorite game of all time that I never want to play again.

SNES Doom started as an experiment by programmer Randy Linden, who built a working prototype using a development kit built from a “hacked up StarFox cartridge” (to leverage its Super FX II chip) and an Amiga. His work pushed the 16-bit hardware to its absolute limits, leaving just 16 bytes of free space on its cartridge. He then demoed his work to Sculptured Software, who agreed to help get the game ready in time for the 1995 holiday shopping season.

For a Doom-obsessed ten-year-old with a love for Nintendo (and without a PC), this was excellent timing. I had become enamored with the game after playing the shareware version on my grandparent’s computer in suburban Milwaukee (just two hours east from the University of Wisconsin, where the first copy of Doom was uploaded to a server in 1993).

Navigating a monster-infested Martian moon base through a first-person perspective was revelatory. So was the game’s frightening sense of suspense and over-the-top gore. At the time, the most powerful gaming system my family owned was a Sega Game Gear, and the most violent game I’d ever played might have been the original side-scrolling Duke Nukem at a friend’s house. This was a significant step forward from those experiences and it was unbelievable that a game could feel so immersive. Or that my grandpa would own anything so bloody. Or that I’d even be allowed to play it.

I felt like a changed man.

After that trip to my grandparent’s house, my family departed to our new home in Cavalier, North Dakota (pop. 1,500), where the United States Air Force decided we were going to be stationed, and I was going to suffer unfathomable depths of boredom. I spent the following months daydreaming about Doom, which had completely rewired my adolescent mind. Sonic The Hedgehog (the edgier alternative to Mario in those days) felt like a childish diversion compared to its dark 3D corridors and pulsing heavy metal soundtrack. Convinced that I’d seen the future of interactive entertainment, no other game could compete for my attention at all.

The only problem was my family didn’t own a computer. We would not own a computer for many more years. Regardless, I absolutely needed to get my hands on Doom. My life depended on it.

So, you can imagine my shock when I first saw Doom for SNES. It was just out of reach behind glass in a video game kiosk at Sears, and it was the most glorious thing I had ever seen. I didn’t know how the hell it was possible to fit a game that was so realistic on a 16-bit console; it turns out the answer is “not very well and with lots of sacrifices” (the source code is available here if you want to try to figure it out). Critical reception for Doom on SNES was lukewarm, and today, the game is better remembered as a novelty rather than a groundbreaking classic.

I didn’t care. All that mattered was Doom existed on a console I could conceivably convince my parents to buy. In that moment, I knew exactly what I was getting for Christmas.

My parents obliged, probably hoping if they bought me Doom, then I would finally shut up about it. Never mind that they paid a full $80 for a nearly three-year-old shooter that was once available on PC for free. Nor that the Super Nintendo was nearing the end of its commercial lifespan and that my best friend had just gotten a PlayStation (an expensive non-Nintendo console I knew nothing about, that had received a vastly superior Doom port). Those facts were immaterial when I unwrapped my SNES and Doom, feeling like I was holding something too good to be true (even if I didn’t realize it mostly was too good to be true).

The box art was about the only area where this version of Doom was equal to its PC counterpart. Fortunately, I didn’t exactly remember what it was like on the computer, so I didn’t notice the difference in performance or visual detail (both of which were roughly cut in half). As a bored kid living far away from anything that felt familiar, there was only one thing I cared about, and that was slaughtering all of Hell’s army. In space.

I invested hours crawling through the game’s labyrinthine level design, not realizing many of the levels had been edited down to make it onto an SNES cartridge. Since the game lacked a save mechanism, turning the power off so someone else could watch TV meant having to start over the next time I fired it up. Undeterred, I’d diligently try to get as far as I could (which was the third level of the third episode) before being asked to do my homework or go outside.

My obsession with Doom grew even as I grew tired of my other games. I bought the SNES-specific strategy guide (which now sells for more than I would have guessed on eBay). All four Doom novelizations soon lined my bookshelf, too. I swore they were literary genius but they were probably garbage. When my friends said the pixelated graphics of SNES Doom didn’t “look real,” I’d tell them they were “so wrong.” This was my first taste of pop-culture fandom that felt like something I needed to defend. Something that felt like it was my own.

Eventually, I sold my Super Nintendo to get a PlayStation for Tomb Raider, the next leap in my maturing tastes. Parting with my copy of Doom made this difficult. I tried to find something similar for Sony’s 32-bit grey box, but I could never track down a copy of the original Doom on PSone, and Final Doom couldn’t recapture the same magic. I pined for Alien Trilogy, but by the time I had the system to play it on, it was impossible to find. Disruptor was solid but didn’t scratch the same itch. Once I got an N64, I thought Doom 64 and Turok would recapture the magic of SNES Doom, but they didn’t. They weren’t bad. They just weren’t the same.

And if anyone remembers PO’ed or Kileak: The DNA Imperative, I feel your pain too, buddy.

My fascination with Doom and the first-person shooter genre faded. I rediscovered a similar sense of tension and fear in Resident Evil, but nothing could equal the experience of SNES Doom in all its 16-bit glory. Randy Linden’s vision for how the game could run on such basic hardware left an impression on my young mind, and those memories couldn’t be replaced.

As I’d learn years later, however, they could be shattered.

SNES Doom has long been criticized for being a woefully sub-par port. Stacked against its PC forefather, its painfully evident that it possessed all the spirit of the original, but none of its polish. Even in the mid-1990s, someone who was intimately familiar with the game on DOS would still recognize it as Doom, but they’d never put the two versions on equal footing.

When I play the PC version of Doom now as an adult, it plays the way I remember SNES Doom as a kid. I’m able to quickly move around maps through sheer force of muscle memory, unlocking secret areas I thought I’d long forgot. As a piece of gaming history that set the foundation for an entire genre (alongside its sister franchise Wolfenstein), it’s still worth revisiting for a few bucks on Steam or various current consoles.

The same can’t be said for SNES Doom, which absolutely does not play the way remember it at all (though it’s a testament to my childhood imagination that I once thought it was great). While my nostalgia for it will never die (even if it should), it’s a blunt reminder that my favorite video game from when I was growing up isn’t very good. Floor and ceiling textures are missing. Rockets face the player when leaving the rocket launcher barrel for some reason. Enemies blend into backgrounds. Every other frame of animation feels like it’s missing. It’s not good.

The game’s audio and visual deficiencies have tactical consequences, too. Get too close to a wall and you’re liable to get stuck while enemies tear you apart. Since enemies are only animated from the front, there’s no way to sneak up on them from behind, nor bait them into a crossfire. Circle-strafing was also removed in lieu of side-stepping. Ambient sound has no impact on enemy movement so feel free to be as loud. No one’s coming to look for you.

Some of these flaws are obvious. Some I didn’t even realize without researching. All of them add up to an inferior port of a reheated shooter that I loved way too much.

I thought that revisiting SNES Doom as an adult would be fun, and in some ways, it is. But it also feels like willfully shredding fond memories from my youth and replacing them with some cold, hard truth. While I’d never take back the time I spent on it, I have to admit the naysayers were right. The game sucked.

———

Ben Sailer is a writer based out of Fargo, ND, where he survives the cold with his wife and dog. His writing also regularly appears in New Noise Magazine.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 153.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!