The Best of Worlds

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #144. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Architecture and games.

———

I came across an interesting article in the news. The argument was that a certain megacorporation could make life better for its workers by relocating some of its factories to cities with a low cost of living. The writer also discussed employee benefits like subsidized housing and recreational facilities. I could barely contain my sense of skepticism. This looks pretty good on paper, but the fact of the matter is that megacorporations have tried pulling this kind of thing before. They always messed things up. The best examples come from the early days of progressivism just before the turn of the twentieth century. Some of this finds a reflection in BioShock Infinite in the form of Columbia.

Columbia was designed to be a showcase for American values. The point of this flying city was to spread freedom and democracy by demonstrating what these principles were capable of accomplishing in terms of economic progress. The leader of Columbia, Zachary Comstock, turned his back on America, though. He decided to pursue his own vision of a perfect society by declaring independence. This of course meant racism, authoritarianism and paternalism. The idea was basically that everybody should stay in their place for the benefit of the common good. The elite of society was properly rewarded for its leadership of the ignorant masses who couldn’t otherwise provide for themselves. What emerged was a movement for emancipation which met with the full force of the military. The people united to free themselves. They were given the boot.

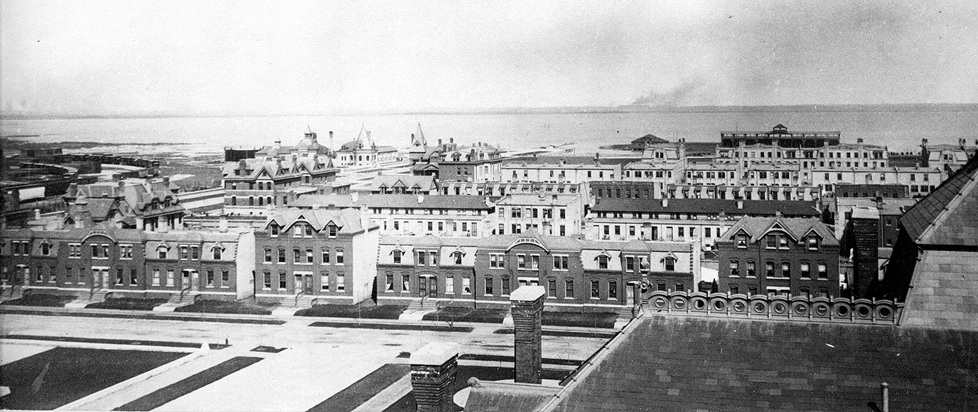

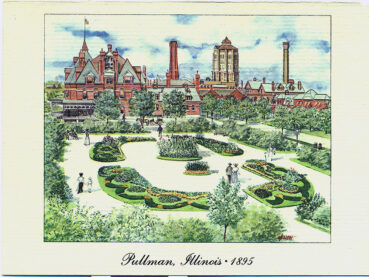

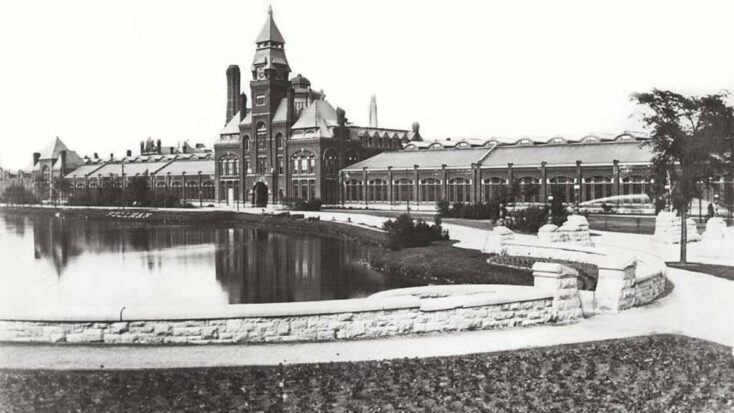

Something along the lines of Columbia can be seen in the town of Pullman, Illinois. The place was founded in 1880 by a wealthy industrialist named George Pullman. Having made a fortune during the Raising of Chicago by developing a method of elevating an entire city block some five feet off the ground, he started the Pullman Company in 1862, which soon gained what amounted to a monopoly on sleeping cars. These were leased out to various railroad companies. Pullman advocated for worker protections and welfare, so when demand for sleeping cars outpaced the production capacity of the Pullman Company, the decision was made to build a new factory a mile or two south of Chicago. The plan involved founding a town for his employees that would, of course, be called Pullman. The idea was that everybody would stand to benefit. Workers would get better living conditions and the Pullman Company would reap the rewards of improved efficiency. In comparison to Chicago, Pullman looked a lot like paradise. The residents weren’t fooled for long.

Everything in Pullman was owned by the Pullman Company. This included a library, theater, hotel, church, park, shopping mall, water treatment facility and over 1,400 homes. The latter had running water, gas, plumbing and garbage removal. The brick buildings were made in the “advanced secular gothic” style, so they featured high ceilings and big windows. These looked pretty good to anyone living in a dirty tenement in Chicago. The only downside was forced adherence to a strict code of moral standards. You had to mind your manners if you wanted to secure a place for yourself in this paradise called Pullman. The idea was to create the best of worlds, but the place turned into a dystopia. Pullman wanted to reform and uplift his workers. The official statement was that Pullman was founded to surround the workers of the Pullman Company with “such influences as would tend to bring out the highest and best there was in them.” He basically just put them in prison. The only place where you could buy alcohol was the hotel bar. Women were expected to stay home unless they were accompanied by their husbands. Black people were kept out of town.

Pullman was praised as an experiment in equality. The economist Richard Ely pointed out that Pullman consisted of identical buildings without any “favorable sites” for “drones living on past accumulations of wealth.” While some referred to Pullman as the “youngest and most perfect city in the world,” others like Ely more accurately described the town as an exercise in “benevolent, well-wishing feudalism.” Residents had no say in how the place was managed. There was an official responsible for city services including road repair, utility maintenance, garbage removal and fire protection who also happened to be in charge of the shopping mall, hotel and church. You paid this person rent. You bought your food from his grocery stores. Your children went to a school that he supervised. This official had nine deputies and something like 300 agents. There wasn’t a single person among them elected by the residents of Pullman. They were all employees of the Pullman Company who answered only to Pullman. You can imagine how things developed. These agents were notorious for entering homes without notice to repaint walls and replace fixtures. The expenses were taken directly from paychecks. They often broke in just to make sure that people were maintaining their moral obligations.

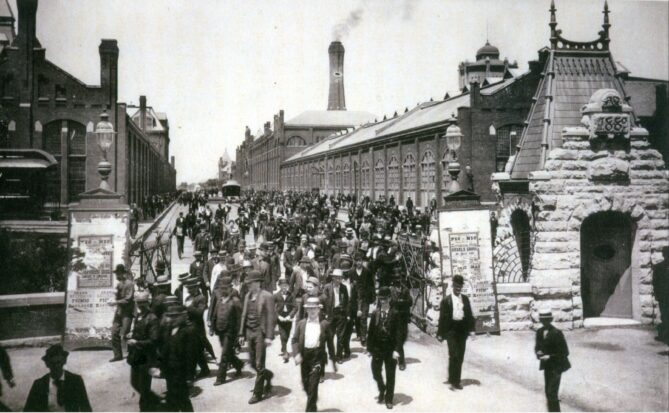

The residents of Pullman decided that enough was enough in 1894. The trigger was a pay cut accompanied by rising rents and a skyrocketing cost of living. The economy fell into a slump after the Panic of 1893. Demand for sleeping cars plummeted. Pullman had to lay off some of his employees and make life a lot more difficult for everyone else. Things came to a head when over 4,000 workers walked off the job in 1894. The leader of the American Railway Union, Eugene Debs, began organizing the strikers in Pullman, calling on them to “resist the plutocracy and arrogant monopoly.” Debs launched a boycott against all of the railroad companies that were leasing sleeper cars from Pullman. The move stopped thousands of trains dead in their tracks. This boycott involved some 250,000 workers in 27 states. Tasked by President Grover Cleveland to put an end to things, the Attorney General at the time, Richard Olney, found grounds for an injunction against the strikers on the pretext that mail couldn’t be delivered. Debs refused to back down. Cleveland called in the military. There were at least 30 people killed by the 12,000 soldiers that invaded Chicago. The strike was broken.

Pullman provides a reminder that megacorporations can’t be trusted to pursue any sort of progressive politics. They aren’t about making life better for their employees. They’re about making life better for their shareholders. Pullman could never have been a paradise because the place was founded on the principles of racism, authoritarianism and paternalism. The megacorporations of today are no better suited to the task of running a town. They might look pretty good on paper, but when it comes to the realities of daily life, utopias like these always turn into dystopias. The city of Columbia in BioShock Infinite gives you some insight into what this really means. Since a lot of time has passed, you might not grasp what things were like in Pullman, but if you play BioShock Infinite, you can relive the strike in a certain sense.

What you need to remember is that Columbia isn’t exactly fictional. Similar cities existed in the past and could very well exist in the future. Pullman is the perfect example. The town was an exercise in “benevolent, well-wishing feudalism” in the best of cases. Whenever someone tries to convince you that a megacorporation is going to make life better for its workers, I want you to remember Debs and the 4,000 people who turned their backs on Pullman. They suffered until they just couldn’t take it anymore. Learn from their mistakes. Don’t fall into the same trap.

———

Justin Reeve is an archaeologist specializing in architecture, urbanism and spatial theory, but he can frequently be found writing about videogames, too. You can follow him on Twitter @JustinAndyReeve.