Socialism in One Solar System

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #123. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #123. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Adam examines the reasons why he and the pop culture consensus differ in opinion.

———

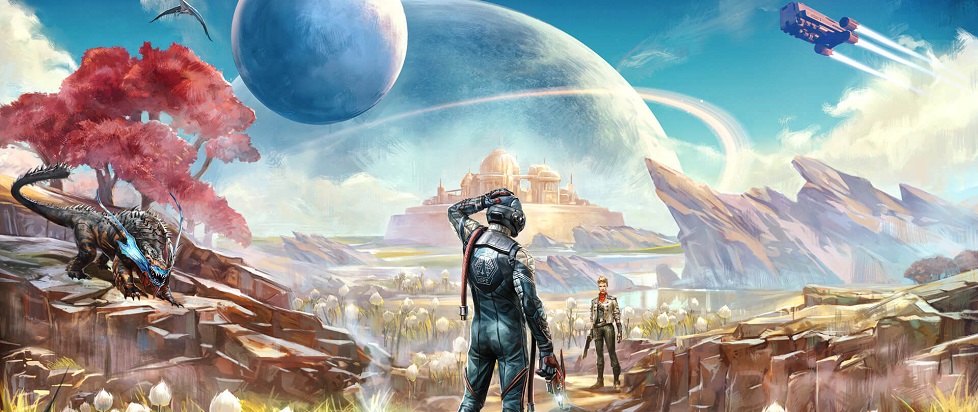

Upon release this past fall, The Outer Worlds gained attention for its skeptical attitude toward capitalism. In the future imagined here, people live in Halcyon, a colony spread across a number of planets in a distant solar system. Halcyon was developed and is now owned and managed entirely by a handful of corporations (there is no independent government) and the results for most people living in the colony have been disastrous. The Outer Worlds routinely highlights the impacts of corporate governance on society through the colony’s persistent problems with ecological breakdown, gross inequality, heinous working conditions and malnutrition, among other issues. Its tone is irreverent throughout, but the game has capitalism squarely in its targets.

Alongside its dystopian setting, the game also made headlines thanks to its inclusion of moments that force the player to make major choices about the direction of life in Halcyon. Some observers noted that these sections surprised them by complicating their expectations and challenging their own political assumptions, leading these players to make choices they had initially dismissed.

But these major decision moments reveal a hollowness in The Outer Worlds’ conception of politics. They point to a tension that runs throughout the game and weakens its storytelling. While its critique of capitalism goes beyond the superficial, The Outer Worlds does not have a similar depth of understanding of the alternatives.

The first momentous choice that the player faces involves settling a dispute about scarce resources between a company town and a group of deserters. The town, Edgewater, has been struggling as a result of corporate-imposed food and medicine rationing, along with overwork. The deserters object to these conditions and have made their own settlement in a botanical lab nearby, where they have been able to rehabilitate some of the area’s poisoned soil and can now farm and provide their own food without relying on corporate dispersals.

There isn’t enough electrical power to support both communities, so the player must choose to direct power to one or the other (or find some sort of compromise). To get to that point, though, the player first has to speak with the leader of the deserters, Adelaide McDevitt. This is the head of an organized group that presumably opposes the inequalities imposed by the corporate power structure and is laboring to establish a more equitable and autonomous community.

But Adelaide’s characterization exemplifies the game’s approach to dissenting politics. The player learns that Adelaide’s commitment to building a new society developed out of a personal feud with the leader of Edgewater – she blames him for her son’s death – and the game depicts her as growing increasingly spiteful and vindictive. This corrodes her ability to lead with responsibility and compassion, and instead the game sees her adopting a despotic stance. If the player decides to support Adelaide’s deserter community instead of Edgewater, the game’s ending reveals that she ultimately refused to accept many of the town’s refugees, leading them to starve. Her research into soil rehabilitation may not have even been especially useful to the colony at large, rendering the entire project questionable.

This kind of portrayal recurs throughout the game. Later on, the player meets Graham Bryant, the leader of a group called the Iconoclasts that is ostensibly engaged in a revolutionary struggle against corporate governance. But the game quickly shows Graham to be a religious zealot wholly out of touch with the material needs of his movement. He routinely puts both his supporters and their broader mission at risk thanks to his stubborn commitment to pushing propaganda at the expense of all else. The player eventually has the opportunity to replace Graham with a different leader, but the ideal outcome of that subplot also involves a reorientation of the Iconoclasts toward a different mission. The game thoroughly establishes that the group’s early, radical formulation was based on faulty premises embodied by Graham.

The game portrays both Adelaide and Graham as aloof and generally clueless; they monologue vaguely on spirituality when asked about matters of strategy and survival. This depiction often feels like it has a goal of parodying tropes associated with New Age spirituality rather than anything related to the failures and mistakes of revolutionary figures. The implication here is that these leaders are unserious and that the same is true of their movements by association. There’s little here that suggests an actually liberatory politics.

But I’m not expecting the game to specifically endorse or agree with my particular political viewpoint. The Outer Worlds is satire, and it doesn’t have to limit itself to satirizing capitalism and its many failures. The problem is that, by trying to satirize radical politics in a superficial way, the game weakens its own storytelling and capacity for player engagement. Because the game continually foregrounds opposition movements that are impractical, selfish and devoid of political coherence, it demonstrates that it doesn’t understand why radical politics might be appealing to people living under capitalist exploitation in the first place. The player doesn’t get a strong sense of why someone might join one of these movements.

This lack of appeal undermines the game’s ambitions, as it loses the ability to satirize something more substantial, like the gap between expectation and reality – the promise of a radical proposal and the disappointments encountered in pursuing it. Neither is there a real comprehension of the kinds of compromises that radical movements have historically had to confront, or the justifications made for decisions gone horribly wrong. If The Outer Worlds’ ridiculing of capitalism feels like it’s also illuminating the crises at the core of our political economy, there’s nothing as enlightening in its send-up of the alternatives.

This means that the major decisions the game asks players to make don’t feel meaningful. These moments don’t present players with a tough choice between an existing nightmare and a flawed alternative, but instead repeatedly make the player pick between two things that both feel downright ridiculous. This limits the game’s emotional and satirical potential.

The Outer Worlds’ refusal to engage in a more serious consideration of left politics also limits the scope of its narrative. Because the game expresses so little confidence in the political projects of its most radical characters, it isn’t clear what political goal the player is heading toward in the main narrative. If the player chooses to confront and finally overthrow the corporate structure, the endings don’t say much about the kinds of social or economic relations the surviving colonists hope to create for themselves. Maybe this stems from some anxiety around using terms like “communism” or “socialism” in a mainstream release, but whatever the case, it feels like a notable omission.

As a result, the player only has the game’s rough sketches of a brighter future to go by, and these feel a little internally conflicted. Much of the game’s overall narrative focuses on the passengers of the spaceship Hope, who represent a kind of “best and brightest” from Earth: exceptionally skilled and intelligent professionals who apparently have the knowledge and experience needed to usher in a new era for the colony. The most optimistic of the game’s possible endings has the Hope’s passengers taking their rightful positions overseeing the development of the colony, helping to bring about advances in fields like science and technology that lead to greater fortunes for the colony as a whole.

There’s a kind of faith in a meritocratic hierarchy here, in the idea that there are people who are uniquely smart and skilled who are most capable of shepherding society, and also most deserving of the responsibility. A less generous interpretation would see this as indicating a distrust of the wider public – a belief that the public at large is incapable of sustaining itself, and even prospering, without being directed by some dedicated managerial class. This might help explain some of the game’s political shortcomings: it doesn’t trust the public at large with self-determination. Its conception of leftist politics would then necessarily be pretty limited.

But the game’s conclusion also touches on more surprising themes that help differentiate it from some of its satirical peers and predecessors. The ending notes that the player’s actions created an opening for a brighter future for the colony, but also highlights the fact that the following years involved a great deal of work in order to ensure that the promise of a more just society could be realized. The surviving colonists had to endure difficult years – the problems created by interplanetary capitalism did not disappear overnight – while retaining their belief in and commitment to something better. Gradually, though, they joined together and created the foundation for a new world.

This speaks to an acknowledgement that the work of building a freer society is ongoing but worthy, that a new world doesn’t come about as a result of one dramatic action but from the continual efforts and persistence of entire communities. There’s a belief here, underneath the layers of attempted satire, that people have the means to create the future they want and deserve if they band together. It’s this underlying notion that distinguishes the game from something like Grand Theft Auto V, which also satirizes both capitalism and its detractors. Where GTAV feels dismissive, cynical and fatalist, The Outer Worlds at its best doesn’t encourage the same misanthropic impulses.

This ultimately signals a key problem with The Outer Worlds: its potential feels frustratingly unrealized. Despite its mapping of the nightmares of capitalism and its hints of genuine optimism, the game never expresses any faith in the political traditions that offer the most formidable responses to dystopia. For a game set in the 24th century, this feels like a strange lapse of imagination. The need to envision a better world remains. Even in space.

———

Adam Boffa is a writer and musician from New Jersey.