Building Empire: Arrow Video’s Enter the Video Store – Empire of Screams Collection

Like many people of my age and proclivities, I grew up with Full Moon movies. For those whose youths were less misspent, Full Moon was a production shingle run by Charles Band that churned out direct-to-video horror and sci-fi movies, often involving diminutive little stop-motion monsters. Of these, the long-running Puppet Master series is probably the most famous, though it is only one of many.

Before Full Moon, though, there was Empire International Pictures. Empire was a lot like Full Moon, in that it was also run by Band, and tended to produce low-rent versions of more popular movies, with enthusiasm that pretty much always outstripped their budgets. Likely the best-known movies that Empire ever put out were things like Re-Animator and From Beyond.

As you may have already been able to gather from the titles I’ve listed thus far, Charles Band tended to produce trash, whether it was through Full Moon or Empire. But trash is not a quality judgment, merely a category. There is good trash and bad trash, and during its heyday, Full Moon produced great trash. Empire, on the other hand, sometimes produced some of the very best trash ever made – and maybe occasionally even rose beyond the limitations of “trash” altogether.

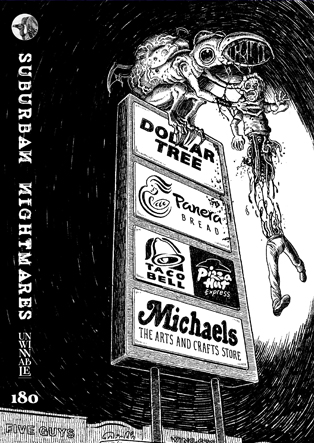

In their latest boxed set, Arrow Video pays tribute to these days of amazing trash at your local video store, with a collection of five films spanning nearly the entirety of Empire’s short tenure. As with any Arrow release, the discs are loaded with extras, including a nearly book-length magazine devoted to the production company. The films here are, with one exception, not the best that Empire ever produced, but they are never short of great trash, and they have never been presented better.

The boxed set itself is designed on the outside to look like a video store, with artwork by Laurie Greasley depicting various characters from the films, while inside the box each movie is packaged in the usual sturdy plastic case, complete with reversible sleeves featuring original and newly commissioned art. It’s the kind of admirably appealing package that most of us probably never dreamed these kinds of movies would ever see back when we were renting them on VHS from our local video store, and it is most welcome.

“I’m having a very bad dream and you just happen to be in it.” – The Dungeonmaster (1984)

My first exposure to The Dungeonmaster came years before I ever actually saw the film, as a sample in a Skinny Puppy song. Richard Moll as Mestema intoning, “There is no way to penetrate this barrier. It has the strength of a million souls; the power of the dead.” The line stuck in my head enough that it eventually inspired the title of one of my stories, originally published in the now-defunct superhero-themed journal A Thousand Faces, more recently reprinted in my latest collection from Word Horde.

Like most things about Dungeonmaster, the actual moment with the line doesn’t make a whole lot of sense and is kind of disappointing. Paul Bradford (Jeffrey Byron) is a computer programmer who, thanks to an undisclosed experiment, can “link up” with his semi-sentient computer, X-CaliBR8 or “Cal.” This gives him a leg up in the computer repair business, but is causing friction in his relationship with his human girlfriend, Gwen (Leslie Wing, Zac Efron’s mom on High School Musical).

For some reason, this attracts the attention of Mestema (the aforementioned Richard Moll), a demonic sorcerer who, the film implies, might actually be the Devil himself. Mestema teleports Paul and Gwen to his hellish dimension while they sleep and proceeds to put them through seven “challenges.” Well, mainly Paul. Gwen spends most of her time chained to a rock.

Aside from the nonsensical nature of its premise, these challenges are what sets Dungeonmaster apart. Each one is essentially a (very) short segment in an anthology film, helmed by a different director, and usually in a different genre. There’s a confrontation with gnarly living corpses and a weird puppet creature in John Carl Buechler’s segment, a slasher-style killer in a segment directed by Steve Ford (son of former president Gerald Ford), a Mad Max-ish apocalyptic future in Ted Nicolaou’s segment, and what is essentially a music video for the heavy metal band W.A.S.P. in Charles Band’s contribution, to name a few.

With the exception of “Slasher,” the sequences are really all too short to contribute much, but their quantity and pedigree means that Dungeonmaster makes a pretty perfect first movie for a Blu-ray set skipping across the surface of the Empire Pictures oeuvre, as this collection does. This is because just about everyone working on Dungeonmaster is someone who will also be involved in plenty of other Empire Pictures releases, from some of the names already mentioned to folks like Peter Manoogian and stop-motion impresario Dave Allen, whose style is as synonymous with the later Full Moon brand as Charles Band’s name.

Perhaps ironically, given my introduction to the film, probably the most lasting impact that Dungeonmaster has had on popular culture comes from a different line of dialogue, this one spouted by Paul in defiance of Mestema: “I reject your reality and I substitute my own.” This phrase, quoted and popularized by Adam Savage on MythBusters, has become an internet meme, effectively meaning that countless people know the line without having any idea what movie it’s from – just as I once knew the other line from that Skinny Puppy song.

“Sometimes bad dreams can really be good for you.” – Dolls (1987)

I said earlier that Empire/Full Moon mostly made trash, even when they were making especially good trash. And that’s more true than not, though every now and then (usually when Stuart Gordon was behind the camera), they made movies that jumped outside the bounds even of “really good trash” into just fully great films that are merely wearing the trappings of trash. Re-Animator and From Beyond are certainly contenders and, for my money, Gordon’s follow-up to those two films is absolute proof.

Dolls is a movie that gets widely underestimated, even by me, and I love it more than just about anyone. Even though I know I love it, every time I watch it, I expect it to just be really good trash that happens to hit my particular triggers. And every time it absolutely floors me anew with how perfect it all is. Why is that? Maybe it’s the fact that a movie about killer dolls should probably not be this good. Maybe it’s the way the film skips across subgenres, sampling from the old dark house pictures of yesteryear as liberally as it borrows fairytale imagery – its writer also penned Troll the year before, after all.

And yet, pretty much every second of Dolls’ delightfully brief 77-minute running time works perfectly, even if it is perfectly trying to be something that pretty much no other movie has ever even attempted, for better or worse. For anyone who doesn’t think this movie is perfect, I challenge you to watch the sequence where one of the very British punk girls smashes a bunch of the dolls, revealing the weird, creepy little mummies they really are underneath.

As it happens, this is another movie that inspired one of my stories. In this case, it lent more than merely a title. The title story of my third collection, Guignol & Other Sardonic Tales, owes its genesis to the attic of this film’s old dark house, with its creepy old torture implements, and to the unforgettably grisly fate of punk girl Isabel, played by Bunty Bailey, the girl from the video for a-ha’s “Take On Me.”

“To contemplate evil is to ask evil home.” – Cellar Dweller (1988)

If Dolls feels like something better than it should be, Cellar Dweller feels like a feature-length episode of Tales from the Crypt – but not in a bad way. If you’re at all familiar with these movies, you won’t need to be told that Cellar Dweller is directed by John Carl Buechler. Despite the breadth of his filmic experience, Buechler’s distinctive visual effects style is perhaps most closely associated with the Ghoulies franchise, and the eponymous dweller in this film looks like nothing more than an oversized Ghoulie.

The premise here is utterly delightful. Jeffrey Combs plays a pre-Code comic book artist named Colin Childress who is drawing EC-style horror comics in an all-too-brief prologue. (In one of the film’s best moves, the comic book company in question is Empire International Comics, with a logo made to mimic the classic EC.) Combs’ artist is taking inspiration from an old grimoire when he accidentally conjures up the beast that he is drawing, which kills a victim (also conjured up by his art) and then leads the artist to inadvertently burn himself alive.

The art that we see Childress drawing was provided by Marvel Comics regular Frank Brunner, and it’s not really a knock against the rest of the movie to say that it never gets better than Jeffrey Combs drawing Frank Brunner art.

From there, we flash-forward 30 years. The house has become an artist’s colony – allowing the filmmakers to have plenty of fun at the expense of artistic pretension – and an up-and-coming cartoonist has come there to study expressly because it was the home of her hero, Colin Childress. Of course, it isn’t long before she finds the grimoire and conjures up the same beastie, which makes relatively short work of the rest of the house’s inhabitants – in fine Empire form, the whole movie is only 77 minutes long, after all.

The attraction here may be the monster, but the real appeal comes as the film harkens (cheaply) back to older styles of storytelling, from the horror comics that inspired it (each of the film’s kill sequences is accompanied by an illustrated version) to the Universal monster movies of yesteryear. At the end of the picture, when the credits roll, they borrow Universal’s old “a good cast is worth repeating” header.

“As long as there are Steve Armstrongs out there in the universe, there will always be contenders.” – Arena (1989)

Did you ever watch Babylon 5 or Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and think, “This is great, but I wish it was about boxing?” If so, have I got the movie for you!

It isn’t much of a stretch to assume that Arena is one of the most ambitious films that Empire ever put out. Directed by Peter Manoogian, who helmed probably the worst segment of The Dungeonmaster and went on to direct several Full Moon movies, including the original Demonic Toys, Arena goes way beyond just being Rocky in spaaaaaaaace! – though it’s emphatically that, too.

Set in the year 4038, Arena assumes that people that far in the future still give a shit about boxing, never mind that boxing actually experienced a precipitous decline in popularity even since this movie was made. The action here takes place on a space station where the big match is held. The station is festooned with a regular Mos Eisley cantina of various rubbery alien weirdos, brought to life by special effects artists including the likes of John Carl Buechler and Screaming Mad George.

The film’s underdog story comes from the fact that there hasn’t been a human champion in the eponymous Arena in 50 years (ignore the fact that the marketing frequently says 1000). That all changes with the arrival of Steve Armstrong (Paul Satterfield, Creepshow 2), a disillusioned former short order cook who trained his whole life to fight in the Arena only to find that all the “sport” had gone out of it by the time he arrived. Even the film seems to know that it goes without saying that Armstrong will quickly rise to the top and challenge Horn, the current reigning champion, and only a cursory amount of time is given to his battles with various other alien critters, the high point of which is the locust-like Sloth.

The connections to Babylon 5 and Deep Space Nine are more than skin deep, too. Babylon 5’s Claudia Christian plays Armstrong’s manager, while Marc Alaimo (who played Gul Dukat in DS9) and Armin Shimerman (who played Quark in that same series) are the film’s villain and his rat-faced henchman, respectively. What makes all this particularly surprising is that both of those shows were still years away when Arena arrived on the scene. Deep Space Nine began airing in syndication in 1993, and Babylon 5 first hit the airwaves that same year.

“There’s nothing you can teach me, except how to lose.” – Robot Jox (1989)

Robot Jox was actually the most ambitious film that Empire ever attempted, costing somewhere between 6 and 10 million dollars, depending upon who you ask. Unfortunately for Empire – which was already in the throes of bankruptcy by the time the flick hit screens – Robot Jox made only a fraction of that budget back, an estimated $1.3 million, give or take.

Of the five films in this set, Arena was the only one I hadn’t seen before. But I may as well have never seen Robot Jox. I watched it in college, as part of an interterm (short, oddity courses held over the January break) focused on sci-fi films. From that, I remembered exactly two things: the hover car coming through the wall (I have no idea why; it’s not that memorable) and the infamous chainsaw penis (that one makes more sense). Everything else was essentially new to me.

Robot Jox doesn’t exactly enjoy a great reputation, but it maybe should. Or, at least, a better one than it gets. Sure, it’s ultimately some jingoistic feel-good nonsense a la Arena – it’s probably no surprise here that Top Gun had come out just a couple of years before – but it’s got enough teeth in its mouth to still bite the hand that feeds it here and there.

The premise here is simple enough: Following a nuclear war, war itself has been outlawed, we are told in an opening voiceover, and now all global conflicts are resolved via one-on-one matches between dudes driving giant robots around. I have seen Robot Jox called “the Battletech movie we never got,” and that’s accurate enough, especially for how the mechs look, though director Stuart Gordon has actually cited Transformers, of all things, as one of the inspirations.

The conflict is all Cold War nonsense. The entirety of global politics has been boiled down to two world powers, one of which seems to be pretty much wholly Americans, one of which is represented by a villainous Russian pilot. That’s all pretty standard stuff for the late ‘80s, but there are some sub-Verhoevenian satirical touches, such as the fact that the America stand-in is just called “the Market.”

It’s not high art, but it works more than it doesn’t, and it set the standard for a lot of other stuff that was to come. Indeed, Pacific Rim feels particularly indebted to Robot Jox, a fact that got a fair bit of critical attention when that film hit theaters. Gordon himself, when asked about the film, said that watching Pacific Rim was like “déjà vu” because, had he been able to do a sequel to Robot Jox, it “would have been robots fighting aliens.” (There actually were a few sequels to Robot Jox released via Full Moon, but none involved Gordon or, as far as I know, aliens.)

Which brings us back around to Gordon’s contributions to this film, something that I always forget because Robot Jox feels like an oddity in much of the rest of his filmography. And yet, the story goes that Gordon was the one who brought the idea to Charles Band, and that he had to sell that notoriously frugal producer on it. Ultimately, he was told to make an effects reel with stop motion master Dave Allen, which became the film’s (honestly great-looking) opening sequence.

From there, Gordon brought on sci-fi author Joe Haldeman, who he knew because Gordon had directed a stage adaptation of Haldeman’s famous novel, The Forever War – talk about things that seem unlikely. Haldeman and Gordon apparently disagreed pretty vehemently about what the finished film should be like. Would Haldeman’s version have been better? There is, of course, no way to know. But we can guess that it might not have been as much fun…

———

Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, game designer, and amateur film scholar who loves to write about monsters, movies, and monster movies. He’s the author of several spooky books, including How to See Ghosts & Other Figments. You can find him online at orringrey.com.