A Golden Halo That Could Be the Sun Part II: The Ones Who Stay and Fight

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #164. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Peripatetic. Orientation. Discourse.

———

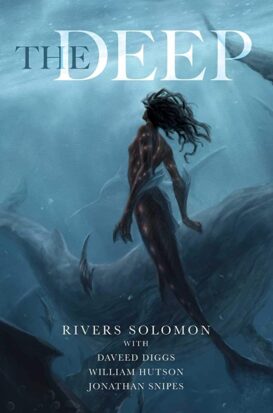

In faer 2019 novella The Deep, Rivers Solomon revises the apocalyptic tsunami of clipping’s speculative single to ask: “What does it mean to be born of the dead?” Inheriting the sea from drowned women during the Atlantic slave trade and having generations since fought the two legs (the same war of clipping’s single), the wajinru manage the trauma of their history by resting all memory in a historian who gives their self up as a vessel to bear the weight of family histories, ancestry and the cultures’ traumatic origins.

The position of historian evokes the child at the center of Omelas. Though they do have a place in the wajinru society around them, the psychic load and sheer trauma of the history contained within the historian untethers them from the present. And unlike Le Guin’s tale, it is in fact the scapegoat that walks – or rather swims – away, forsaking the utopia she grew up supporting. The utopia is, in The Deep, ahistorical. It demands not just the sacrifice of cultural history, but family history and the identity that comes with it. Ultimately the wajinru realize their cruelty and can reconcile moving forward with their past using history as a guide – letting Yetu guide them. That is a future left to us to imagine.

In another version of the story, a colonized people escape slavery in the water. The Talokan, however, make this choice to continue living as conquistadors encroach on their homeland in present day Mexico. Through ritual and potion, they give up their ability to return to land to live in peace beneath the water, hidden from the surface dwelling two legs who go on to colonize the planet. But much like the first Black Panther film’s “build community centers in Oakland” is a bastardization of its titular revolutionary political party, Wakanda Forever contrives boring villainous motives out of the Talokan champion Namor’s attempts to protect his people from colonial governments seeking to extract resources (Vibranium, because Marvel) beneath their surface to preempt any confrontation with the colonial status quo. The film instead finds conflict not between colonized and colonizer, but among the colonized themselves. These two versions of utopia against each other, siding of course with the nonviolent side.

Leila Taylor describes Afrofuturism as a “a nostalgia for what should have been.” Wakanda is a utopia that revises African history, but in its most mainstream form ends up being unable to say very much about the world as it is today. This “Black Panther perception of the world” is still valuable, as Taylor writes of herself in Darkly, but Black Panther goes on to preclude the other kind of utopia – the Black Panther kind, particularly. The Deep is an Afrofuturist myth that imagines what to make from it all; Marvel denies revolution, because the apocalypse is bad when it comes from below.

In another version of the story, in a place where war is almost forgotten, a girl buries a father who almost remembered such antiques. He died so others could forget, and so she would join that endless fight. In Um-Helat, utopia is not built on the sacrifice of an innocent scapegoat, but antifascist action.

———

Autumn Wright is an essayist. They do criticism on games and other media. Find their latest writing at @TheAutumnWright.