Lost Cities

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #148. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Architecture and games.

———

While the game has been rightly criticized for its representation of archaeology, I think that Shadow of the Tomb Raider actually gets a couple of things right. I could speak more broadly about this, but the most interesting approach is to focus on a single subject, so I’m just going to address the topic of lost cities. I should really put quotation marks in there. Let’s talk about “lost” cities. The game is right on the mark when it comes to this particular problem.

We’ve been bombarded with tall tales about lost cities for centuries. The story always goes that an explorer trudging through the jungle notices a statue or something which leads them to a lost city. This has never happened. While the rediscovery of a lost city makes for a great story, the fact of the matter is that somebody always knew about them. The only thing that an explorer ever did was to ask the locals where they should start looking. The reason why settlements were “lost” for so long is that reports of their existence were never taken seriously. The argument was that indigenous people weren’t capable of building cities. I’m not even making this up. The evidence to the contrary came as a shock to most people in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries who had profoundly racist perspectives on human development.

The fact of the matter is that indigenous people still aren’t given much of a part to play in things. The situation in the United States and Canada is that indigenous people are only rarely given the opportunity to participate in the excavation of their own cultural heritage. While they’re interested in digging up their dead, most archaeologists pay no attention to indigenous people. Sid Mills put it pretty bluntly after dozens of indigenous people were beaten by the police during a protest over fishing rights in Washington. He asked what sort of a society would “pick upon our bones” and “protect our ancient remains from damage while at the same time eating upon the flesh of our living people?” Mills noted this in 1965, but almost nothing has changed in the meantime. Indigenous people are still clashing with cops over fishing rights. Archaeologists are still prioritizing the dead over the living.

Shadow of the Tomb Raider pokes a hole in the myth of the lost city by making Paititi a place that was never forgotten or even abandoned. While she comes across a couple of clues about its existence, Lara Croft basically rediscovers the settlement just by asking around. Lost cities including Machu Picchu, Great Zimbabwe, Petra and Tikal were found in exactly this way. This however didn’t stop archaeologists from taking credit for their supposed rediscovery.

Machu Picchu was an estate belonging to the emperor Pachacuti in what now is known as Peru. The site was occupied for a century between about 1420 and 1530. The city consisted of several structures with dry stone walls that were placed on a rectilinear pattern atop a mountain ridge. While some of these were ceremonial, most of them were just utilitarian. The site is best known for its agricultural terraces. The buildings were still standing when the site was “rediscovered” by Hiram Bingham in 1911. The story is basically that Bingham went to Peru to find the last capital of the Inca, Vilcabamba. He actually found this in much the same way as Machu Picchu, but that’s another story. When he arrived in Cusco, Bingham studied the Chronicle of the Augustinians by the priest Antonio de la Calancha. This was published in 1631. The book was a little bit out of date, so Bingham went around asking farmers and miners about the places mentioned by Calancha. The explorer noted that “one old prospector said there were interesting ruins at Machu Picchu,” but added that his claims “were given no importance by the leading citizens.” Having remembered that another explorer, Charles Wiener, heard the same thing from some of the locals, Bingham travelled to Mandor Pampa where he met a hotel owner by the name of Melchor Arteaga. Bingham asked Arteaga if he knew of any lost cities. Arteaga said that he did before leading him to Machu Picchu. When they arrived at the settlement, Bingham and Arteaga found a group of indigenous people that were still farming on the agricultural terraces.

Great Zimbabwe is believed to have been the capital of a kingdom which existed in southern Africa between about 850 and 1450. The city was a center of political power, trade, religion and the arts. Great Zimbabwe had a population of about 15,000 people at its peak. The site consisted of circular structures and a large enclosure that may have been a palace. The walls of this were still standing to a height of about 30 feet when Great Zimbabwe was “rediscovered” by Adam Render in 1867. Similar to Machu Picchu, these used a form of dry stone architecture. The story goes that Render came across the site during a hunting expedition while searching for a place to make his camp. The locals of course pointed him in the direction of Great Zimbabwe. The site was first mentioned by the soldier Vicente Pegado who came across a “fortress built of stones of marvelous size” that had “no mortar joining them” in 1531. Pegado seems to have found the place in much the same way as Render. Great Zimbabwe became known to the world when Render brought another explorer by the name of Karl Mauch to the site in 1871. Since nobody at the time wanted to believe that it could have been constructed by indigenous people, Mauch started associating the city with figures like the Queen of Sheba. This remained the conventional explanation for its existence until Gertrude Thompson carried out excavations at the site in 1929. The government of Rhodesia maintained that Great Zimbabwe was in fact not made by indigenous people until its collapse in 1979.

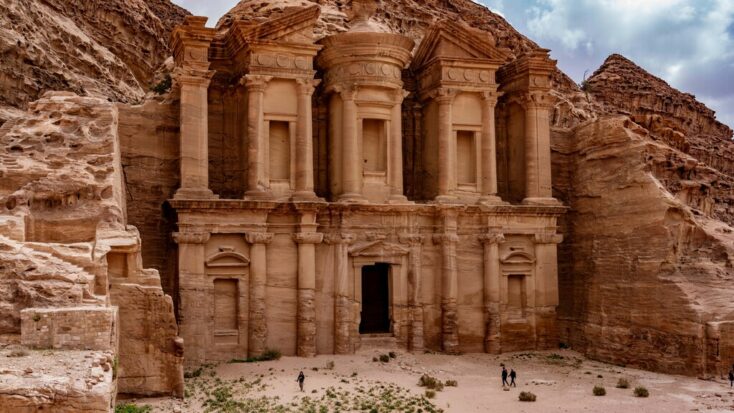

Petra was a city in what is now Jordan. While the site was founded much earlier, Petra flourished between about 50 and 650. The city was mostly supported by trade between Constantinople and Ctesiphon, but similar to so many other places at the time, the backbone of its economy was agriculture. People made use of underground pipes that minimized the amount of water lost. The site consisted of a city center with a temple, theater and garden that featured a public pool. There were several tombs with elaborate facades a short distance away that were all carved into the surrounding mountains. While there were a few other ways into the city, the main point of entry was a narrow gorge that stretched for about a mile through the mountains. Petra was “rediscovered” by Johann Burckhardt in 1812 who came across the site while on his way to central Africa in search of the River Niger. Burckhardt heard about a lost city from the locals which they said contained the tomb of the prophet Aaron. These people led him straight to the city. The explorer even brought a goat with him to sacrifice at the tomb. What he did after finding the site has never been documented, but this goat was probably eaten one way or another. In any case, Burckhardt never found the tomb of the prophet Aaron. The artist Frederic Church followed in his footsteps a few years later, bringing Petra to the world in the form of a painting which depicted the largest of the tombs near the city center. This was completed in 1868.

Tikal was the capital of a kingdom in what is now Guatemala. The city had a population of about 50,000 at its peak. While the settlement was founded several hundred years earlier, Tikal flourished between the second and tenth centuries. The site was abandoned in the eleventh century. Similar to Great Zimbabwe, Tikal was a center of political power, trade, religion and the arts. The settlement was at least 23 square miles in size, but the city center which consisted of palaces, pyramids and theaters covered about six square miles of terrain. These buildings were connected by a series of elevated causeways. The structures were mostly made from stone and many of them were still standing when the city was “rediscovered” by Ambrosio Tut in 1848. This governor was told about the site by some of the locals when he took up office. They described a lost city with buildings that towered above the treetops like mountains. Tut of course didn’t believe them at first, but his curiosity finally got the better of him, so he set off with artist Eusebio Lara to see what he could find. Lara published a description of the site that was complete with illustrations in 1853. Tikal was basically forgotten for about a century afterwards on account of its remote location. This changed with the construction of an airstrip in 1951. Edwin Shook became the first person to carry out excavations at the site a couple of years later in 1957. These were continued by William Coe until they were brought to a close in 1969. The last excavations were between 1979 and 1984.

Machu Picchu, Great Zimbabwe, Petra and Tikal provide a reminder that lost cities have never actually been “lost” in any real sense of the term. Somebody has always known about them. The question at this particular point is why these people were never credited with finding them. The answer is that nobody wanted to believe they even existed because we’re talking about deeply racist individuals who didn’t think that indigenous people were capable of building them.

Shadow of the Tomb Raider gets a lot wrong about archaeology, but the game at least pokes a hole in the myth of the lost city. This speaks in its favor given that most games reinforce the myth of the lost city in the name of things like discovery and exploration. What needs to be remembered is that we’re cutting indigenous people out of the picture whenever we allow ourselves to be carried away by this fantasy. We need to be critical whenever we take on the role of an explorer. The same could be said for books and movies, but games really need to put this particular myth into the dustbin along with a lot of other historical baggage. I really do think that games would be better if more of them gave indigenous people a meaningful part to play in things. We’re talking about their cultural heritage after all here.

———

Justin Reeve is an archaeologist specializing in architecture, urbanism and spatial theory, but he can frequently be found writing about videogames, too. You can follow him on Twitter @JustinAndyReeve.