Parisian Purification

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #145. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Architecture and games.

———

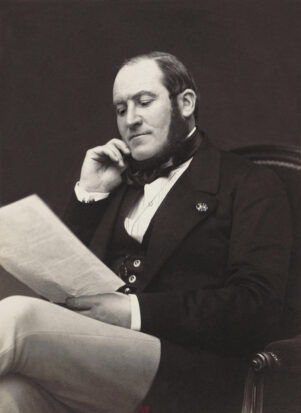

Paris wasn’t always pretty. You’d never believe it by walking around the place, but Paris was the city of muck and mud long before it became the city of lights. The big turning point came in 1853 when a bureaucrat known as Baron Haussmann became Prefect of the Seine. He was hired to “aerify, unify and beautify” the city. Haussmann pulled this off with panache, but he achieved success by running roughshod over its residents. The poorest of these were thrown out of their homes by force and pushed into places like Montmartre, Villette and Belleville where they could easily be ignored by their wealthy neighbors. The point was to keep these people from pulling up the paving stones and building barricades as they did in the revolutions of 1830 and 1848. The plan actually worked out for a while, but the result of this renovation was, of course, another revolution.

Paris was a mess before Haussmann came along. The city was dark, dank and even deadly. Voltaire complained that stalls and stands were “established in narrow streets, showing off their filthiness, spreading infection and causing continuing disorders.” The streets of Paris varied between three and 16 feet in width, so the average distance between buildings was a mere nine feet. These were covered in all kinds of both animal and human waste, causing a terrible stench and allowing for the propagation of disease. Cholera was a constant problem that claimed hundreds, even thousands of lives each year. The deadliness of this disease was compounded by the incredibly high population density. The part of Paris near the Louvre known at the time as Arcis had one resident on average per 32 square feet of real estate. The majority of buildings had three to five stories that were cut up into miniscule apartments of about nine by eight feet in length and width. Since they lacked proper ventilation, these were often full of chimney smoke. They also had no plumbing. There were dozens of people sharing a single apartment.

You can see what this would have looked like by wandering around for a while in pretty much any part of Paris in Assassin’s Creed Unity. This takes place in 1789 as the French Revolution is just about to boil over, but the city looked the same when Haussmann got down to business in 1853. While he had big plans for the place, Napoleon lacked the time to bring any of them to fruition, leaving most of the work to his nephew, Louis, who promptly handed things over to Haussmann. In any case, Paris really isn’t pretty in Assassin’s Creed Unity. The game doesn’t come close to depicting how horrible the place would have been at the time, but you can at least extrapolate based on what you see in the level design. The narrow streets make running around on the rooftops relatively practical. The open sewers are completely clogged with muck and mud. People are all over the place. This was basically what the city looked like before the big renovation.

The last king was overthrown by the French in favor of Louis, going by Napoleon the Second, who became their first president in 1848. Stealing a page from the playbook of his more famous uncle, Napoleon the Second staged a coup in 1851, making him their second emperor. The first thing that he did after firing the Prefect of the Seine, Jean-Jacques Berger, was to bring Haussmann on board. He soon went about aerifying, unifying and beautifying the capital. The laws about eminent domain were expanded in 1851 to allow for the expropriation of land on either side of a new street, so Haussmann faced very little resistance when it came to building a bunch of broad boulevards in between the Louvre and the Bastille, knocking down all sorts of structures in the process. He gave these boulevards their final form with a series of squares. Having done this dirty work, Haussmann got right back to business, ordering the construction of several more boulevards which cut through some of the most crowded parts of the capital. Haussmann called this construction the “gutting of old Paris.” Residents were displaced in droves.

The building of these boulevards went alongside the transformation of the city center. The two islands in the heart of Paris were turned completely upside down, becoming enormous construction sites for most of 1858 and 1859. Several blocks of this densely populated part of the capital were cleared away to make room for a series of public buildings like the Tribunal de Commerce and the Prefecture de Police. These two structures all by themselves took up a lot of the available real estate. Tearing down a bunch of apartment buildings, Haussmann continued his purification of Paris by expanding squares like the Place Dauphine and the Place Notre Dame, leaving hundreds of people homeless. He also built a broad boulevard in between the two bridges known as the Pont Saint-Michel and the Pont au Change that forced even more people to forget about keeping their homes and businesses. The population figures began declining as residents moved to wherever they could find refuge from Haussmann.

Haussmann had six miles of new boulevards on his hands by 1859. He planned on building another 16 miles. Having finished these in 1869, Haussmann began work on 17 more miles of boulevards. These connected 24 squares featuring a variety of public buildings like train stations, markets, theaters and schools. They were lined with hundreds of streetlamps. The most famous feature of his boulevards turned out to be the apartment buildings, though. Structures were deep and narrow before Haussmann came along. Some were made from brick, but most were made from wood. Haussmann mandated the use of stone. While the interior was left up to the owners, the exterior was required by law to follow a particular design, so most apartment buildings were basically the same in plan. There was a ground floor and mezzanine with shops or offices below a second floor with apartments boasting beautifully decorated balconies. There were apartments on the third and fourth floors, but the masonry was much less elaborate than below. The fifth floor had a balcony stretching around the entire structure. The top floor was given dormer windows and a mansard roof.

Haussmann was replaced as Prefect of the Seine by Jean-Charles Alphand in 1870. He had been facing criticism for years, but things finally came to a head as tensions with Germany started heating up, creating all kinds of new controversies. The result was that Haussmann was required to resign. France went to war a couple of months later. While his detractors looked on with “eyes full of tears for the old Paris,” his proponents pointed out that he “brought air, light and healthiness” to the capital, improving circulation in this “labyrinth that was constantly blocked and impenetrable.” The fact of the matter is that Paris would never be the same. Haussmann was very thorough in his work. The only way to get a feeling for what the city was like before he turned the place upside down is to stroll through the streets of Paris in Assassin’s Creed Unity. Haussmann would have been proud. His critics would have been furious. We can only wonder at what might have been.

Haussmann wasn’t all good, but he wasn’t all bad, either. The renovation made Paris far more sanitary, resulting in fewer deaths to cholera and other diseases. The streets were less congested. There were more public buildings. The capital became the city of light, but this transformation came at a cost. People were forced out of their homes and businesses. The population declined in the city center as people fled. Speculators were buying real estate with abandon, so rents were driven to record highs. The result was a revolution after the war with Germany ended in a crushing defeat that placed even more burdens on the poorest people in Paris. While they couldn’t pull up the paving stones and build barricades on account of the new boulevards, residents of the capital took up arms to reclaim their city from the people who evicted them. The social disruption caused by Haussmann set the stage for the revolution of 1871. This turned out to be a failure, though. Haussmann would have his way. Paris remained pretty.

———

Justin Reeve is an archaeologist specializing in architecture, urbanism and spatial theory, but he can frequently be found writing about videogames, too. You can follow him on Twitter @JustinAndyReeve.