Community Will Always Grow

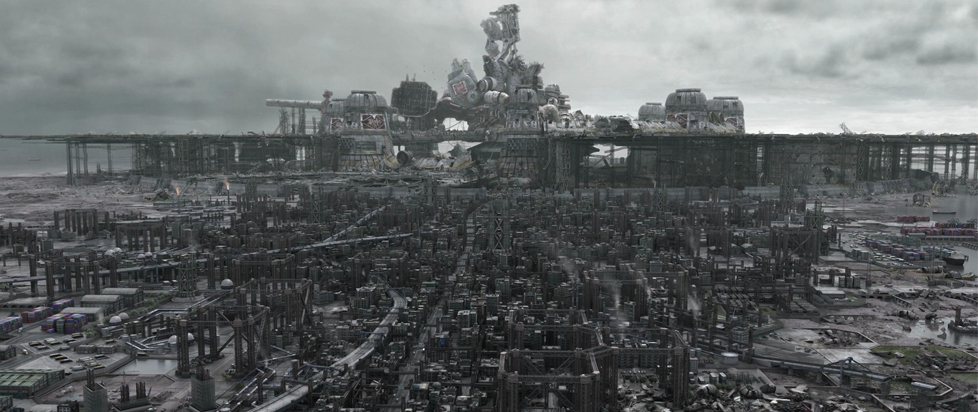

“People hate the steel sky, the slums…but I don’t. How could I? All that passion, all those dreams, flowing and blending together into something greater…”

This is part of Aerith’s explanation to Cloud in Final Fantasy VII Remake for why she couldn’t bring herself to leave Midgar. The outside world is, as she puts it, too much, more than she could handle, whereas Midgar is understandable. She knows it, and more importantly, she knows its inhabitants, being an indelible staple of her local community in Sector 5. The sprawling metropolis is many things to many people, and most of them are bad, but to Aerith and her neighbors, it’s home, one they’ve built over many years. Multiple generations co-exist underneath the shabby tin-roofs and crumbling walls of the slums, all of which have to rely on each other for support. Sure, life could be better elsewhere, but it wouldn’t be together, and that’s something they aren’t willing to sacrifice.

In Final Fantasy VII Remake, Midgar’s as much a technofascist capital as ever, but the heightened realism grants the day-to-day innocence, class struggle and Avalanche’s efforts a much greater clarity than before. Wandering the streets of the lower-class ground layers, you see children playing as their parents work in various small businesses, or hustle for odd jobs. Function is key in the quasi-anarchic infrastructure – entertainment is derived from competing to kill the most monsters in the local red zones, disused rooms are converted to small apartments and old building supplies give the kids somewhere to climb. Side-quests that aren’t clearing wildlife involve mundane tasks like finding lost pets or picking flowers, perhaps boring to us but to the quest-givers they’re everything because cats and daisies are the main comforts when you live in the shadow of Shinra’s pillar.

The slum populace are, like many living in the similarly manufactured Brazilian capital Brasilia, all too aware of the overbearing power structure they exist within. They know class mobility is a lottery at best and they watch as leadership leans further and further into capitalist interest. Yet, in both cities, they cling to the belief that the future they were promised when the city was founded can still be achieved. They remain undeterred because their very existence is proof the underlying ideas have merit and their lives are the only fuel still stoking the fire of those seemingly wild aspirations.

When it was founded in 1960, Brasilia was to herald a new beginning for Brazil. Part of his “50 years in five” campaign plan, President Juscelino Kubitschek de Oliveira made good on his promise to move Brazil’s capital city away from the coastline towards the heart of the country, spreading economic prosperity throughout the nation. Designed and overseen by architect Oscar Niemeyer, urban planner Lucio Costa and landscape designer Roberto Burle Marx, Brasilia was envisioned as a socialist enterprise where government officials and the working class shared the same apartment buildings as Brazil’s economy flourished.

Kubitschek’s vision was short-lived. Fears that Brazil’s socialism would become communism led to a military coup in 1964, installing an authoritarian dictatorship that ran until 1983. All the while, a rural exodus as the cities expanded from the 1950s on caused the urban slums – favelas – to gradually expand, creating and exacerbating widespread drug trade. Corruption and unease have dogged higher political offices, two presidents facing impeachment charges since 1990, leading to a still-ongoing recession that further drives a wedge between the poor and everyone else.

Brasilia now resembles a horizontal Midgar. Those lucky enough to live near the center occupy endless apartment buildings alongside shopping malls. The rich live near and around the man-made Paranoá Lake, on indulgent properties that range into the millions price-wise, and the rest occupy satellite cities, continually pushed out and marginalized. A city structure designed for around 400,000 is currently housing nearly ten times that, and growing.

Wandering the city presents a unique atmosphere. You can see the rising skyline, and the population density, and the winding, inter-connecting roads and chaotic public transport that come with any sprawling municipality, but there isn’t the same bustle as other capitals. Less tourism and fewer concerts or major events. Absent these things, the people find joy in each other. Bars and restaurants are consistently full, patrons keeping local food trucks busy as they move from the hole-in-the-wall pubs at the foot of their buildings up to their balconies for the after-party. The friends I was with often mentioned flying to Sao Paulo or Rio Di Janeiro to see bands play, while making their own fun at home.

Brasilia is far from the egalitarian dream it symbolized. Many who live there feel trapped and isolated, stuck within the gears of economic downturn their presidents are barely trying to fix, forced to constantly reckon with the remnants of that lofty desire. The metro station, where an estimated half-a-million stop by every morning and evening on their commute, is a straight walk to the Monumental Axis, wherein stands the presidential palace and other government buildings, the 60s futurism of Neimeyer’s architecture now a monument to its own ambitions.

Marked at the top by the National Congress, the Axis is a flatland Shinra tower, its waterfalls and pond-life ambiance emanating a science-fiction glow of promise and imminent future. More out of sight than Midgar’s steel sky, but never out of mind for residents, the presidential palaces and its neighboring complexes are power and wealth centralized, just a short drive from where most struggle to hold onto the little they have. There’s a certain unwavering pride in being so close to the heart of the country, and in that pride burns the belief in what Kubitschek wanted Brasilia to be.

In a France 24 news report on Brasilia’s founding, local journalist Daniel Zukko gets emotional thanking Pedro Claudionor, one of the original builders of Brasilia, for not losing faith in the soul of the project. “I am a builder too. This city is not ready,” Daniel says. “I see myself as a builder because we are trying to make it live.” This is what Aerith means, I think, when she speaks of the people in the slums forming into “something greater.” They’re giving Midgar a culture, breathing life into its destitution that isn’t defined by capitalism or who’s in charge. Marle, Ms. Folia, Mireille, Kyrie, Jessie’s parents, they’re all trying to make Midgar live, make it breathe on its own, more than a mere reciprocal for Shinra’s twisted schemes.

Aerith might be naive in her assertion of this passion as a reason not to resent Midgar’s shanty towns, just as Daniel is in his belief Brasilia is unfinished. But without dreams in economic uncertainty, all you have is the misery, the unending, unflinching sorrow that comes from prolonged squalor. As the engine of Shinra’s empire, Midgar makes plain just how far Brasilia has drifted from the intention of its creators. Testaments to opposing views, they are one in the same as markers of classist, anti-environmentalist greed and exploitation. It’s no coincidence, though, that the first sights of Midgar we see in Final Fantasy VII Remake are busy trains and highways, streets full of people living. To Shinra, Midgar is a power-plant, but to the populace on the ground floor and below the plate, who visit the cultural hubs, find solace in local communes and build livelihoods, Midgar is everything. Leadership can try and stamp out opposition, mold spaces through private equity and austerity, but it’s always there, on the fringes, its influence growing right under their nose.

Near the Monumental Axis is the JK Memorial, a gallery and exhibition of Kubitschek’s life and career. His casket serves as the centerpiece, surrounded by various artifacts and personal collections. It’s a short tour, bookended by a modest gift shop – a celebration of someone who saw such greatness in Brazil, sitting now in meek defiance of the current establishment. There’s little such purity to be found in Shinra’s propagandized showcase on the history of Midgar, girded by colonialist desire for the “promised land.” Yet Shinra’s false dream has taken shape in a different way, in the poor who continue to work and fight for each other no matter the cost. Brasilia may have been reshaped by the oppressive, but its idealism burns in the passion of its true believers – all flowing and blending together into something greater.