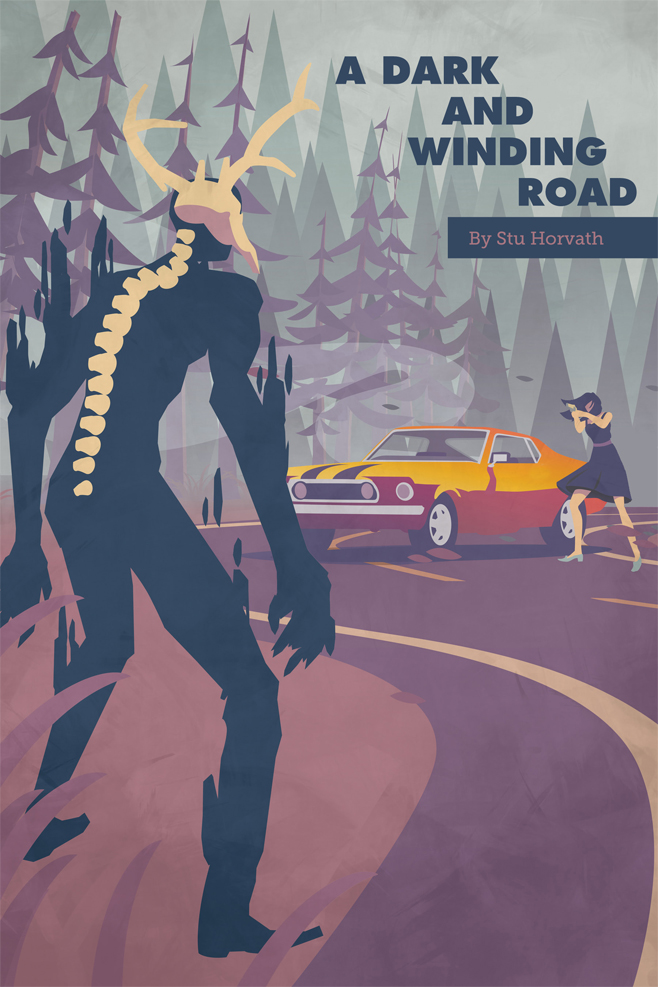

Dead Static Drive: A Dark and Winding Road

This feature is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #123. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

This series of articles is made possible through the generous sponsorship of Epic’s Unreal Engine. While Epic puts us in touch with our subjects, they have no input or approval in the final story.

It starts with a muscle car screaming down a road through a pink-hued desert. The only sound is the motor and the howl of the wind. Ashes fall from the sky. Text appear: Now entering Home Crossing. A moment later, beside the road, appears a parking lot, in which sits a small mobile home. A woman stands next to it.

There is a strange sound now, a kind of insect-like whirring mixed with a deep rumbling. The woman screams, “What…what is that?!” as something rumbles through the ground towards my car, kicking up dust as it goes. Then my car is launched into the air by a pulsating, phallic tentacle thing erupting from the earth. I try to get out the car, stupidly, and hit the pavement, exhaling the words, “Not like this,” as I expire. Welcome to Dead Static Drive.

Each subsequent foray into Home Crossing is different. Sometimes I kill the tentacles (there are many of them lurking in the sand) by running my car into them, sometimes by hacking at them with a hatchet. Sometimes I go to the diner, where synthwave beats slither out of the sound system, and recruit the woman there. Sometimes I accidentally shoot her with the pistol I find on the counter. Sometimes I eat a cherry pie. Sometimes there is a massive spider thing with human arms in the parking lot of another restaurant that incinerates me. Sometimes I run off into the empty desert. Sometimes I drive right out of town, only to reappear right where I started. Sometimes I wear a cowboy hat.

There are maddening hints at a bigger picture. There is a key on the counter, but I don’t know what it opens. One woman says there was nuclear testing in the nearby desert. I can’t shake the feeling that there is something to be found out in the dunes and mesas that might explain what is happening. The people I encounter vary between hysterical and strangely calm. The fact that I keep dying but keep getting up again a few hours later imbues the proceedings with the feeling of being unable to wake up from a nightmare.

* * *

Mike Blackney is the man behind Dead Static Drive. Back when I first interviewed Mike (for Unwinnable Weekly Issue Fifty) it was a solo project, born from his interest in horror, cars and Americana, and it remained so for several years. Because Dead Static Drive is a horror game and I think the best horror comes out of feelings of isolation and helplessness, it is easy for me to picture Mike hunched over a computer in some lonely place like a game developing Herbert West, despite the fact that he now has a talented team and does most of his work in brightly lit cafes. The fact that whenever we chat, we inevitably riff on horror might also have something to do with it.

Mike Blackney is the man behind Dead Static Drive. Back when I first interviewed Mike (for Unwinnable Weekly Issue Fifty) it was a solo project, born from his interest in horror, cars and Americana, and it remained so for several years. Because Dead Static Drive is a horror game and I think the best horror comes out of feelings of isolation and helplessness, it is easy for me to picture Mike hunched over a computer in some lonely place like a game developing Herbert West, despite the fact that he now has a talented team and does most of his work in brightly lit cafes. The fact that whenever we chat, we inevitably riff on horror might also have something to do with it.

This time, we start talking about The Tourist’s Guide to Transylvania, an odd art book from 1981 that reprints a bunch of horror novel cover paintings and tries to tie them together through the narrative conceit of being a travel guide for the most horrific place on earth. Through some cosmic quirk of fate, we both picked up copies for ourselves within a few months of each other.

“I think I was five years old when I was in a library and kids would go and find books with pictures that are scary or sexy (or any other adult stuff),” he says. “I don’t remember who it was but a friend of mine brought the Tourist’s Guide and flicked through it showing some of the pictures. I remember seeing a painting of the undead with gross worms coming out of the zombie’s face. I thought it was saying that zombies are real and if you go to Transylvania you’ll find them.”

* * *

It seems that many people who are drawn to horror as a genre follow a similar trajectory, especially those who discover it young. I was scared of everything when I was a kid, but I also had a fascination with being scared. I had to leave the theater part way through Gremlins, which I saw when I was seven.

We’d gone with my cousins, so my mom and I had to wait in the parking lot for them to come out when the movie was over. Then we all went to dinner, where I gleefully interrogated my cousin for the details, which he gruesomely recounted to my delight and my mom’s absolute confusion. This binary of revulsion and attraction is the cauldron from which many horror fans are born.

It was the original 1981 Evil Dead that hooked Mike. He watched it on a Betamax tape at a friends house, also at the tender age of seven. He wasn’t prepared for the woman under the stairs. “Gave me nightmares for years and I still have trouble looking at her,” he says. Another film, The Video Dead, had him running home after 15 minutes. Even non-horror movies, like Disney’s The Black Hole, had the potential to terrify.

“It’s really strange,” he says. “I didn’t ever feel like I sought out horror so much as people brought it to me.” He credits this to his sisters, particularly his older sister, Brigid, who loved horror but never seemed scared of it. And it was never just movies. Brigid tore through The Stand and Gerald’s Game when other kids were reading young adult books. Having stuff like that justy laying about is going to make a kid curious.

Blackney’s parents, meanwhile, had several horror anthologies on the shelves. He fondly remembers the cover of The Fourth Pan Book of Horror Stories, which sports a campy photograph of a tarantula crawling over an armless doll. “It had one story that we’d lose ourselves talking about all the time,” he recalls. “’Harry’ it was called [by Rosemary Timperley], about a kid whose imaginary friend isn’t imaginary.”

Another anthology, Charles L. Grant’s Gallery of Horror, introduced Mike to the work of T.E.D. Klein, with the story “Petey.” Klein, whose towering reputation as a master is founded on only a small handful of stories, specializes in mixing the cosmic with the commonplace. “I think that’s the kind of horror I’ve naturally been drawn to more – that horror in the mundane,” say Mike. “I also love a lot of David Morrell short stories for similar reasons – they’re more thrillers than classic horror, I guess, but there’s a real sense of place and mundanity in ‘The Dripping’ and ‘Rio Grande Gothic.’ ‘Rio Grande Gothic’ has a man start seeing shoes left near a highway and he’s drawn to the mystery until he finds a shoe with a foot still in it.” Which would sound right at home if it was in Dead Static Drive.

* * *

“I think being exposed to horror through friends was kind of similar to how I was exposed to old cars,” says Mike. With his father in the Air Force, it was fighter jets (and spaceships), rather than cars, that he drew in his notebooks as a kid. Even now, I was surprised to learn, he has never done work on a car – “Though there’s an undercurrent always in the back of my head that I’d love to have the free space sometime to teach myself and get my hands dirty,” he says.

When he was in his mid-teens, his father got a Datsun 280 ZX, the car he’d eventually learn to drive in. And while that was a sharp looking car, it all comes back to movies again. “I had three sisters and no brothers and so the way I saw cars was always in the context of movies about characters or strange situations,” he says. “As a kid, formative years, we re-watched Dirty Dancing, Grease (and Grease II, which I love) and Rocky Horror and they all had some beautiful old cars and bikes, and lots of key moments were leaving or arriving in them.”

During high school, with friends expanding Mike’s horizons into videogames, tabletop roleplaying games, heavy metal, Clive Barker and H.P. Lovecraft, so too did friends introduce him to the beauty of cars.

“I became friends with a kid from down the street, Antony, whose dad was a bit of a car hoarder,” he says. “They had a bunch of cars in their front- and backyard and they were all Valiants and Triumphs. Ant would always be talking about how cool these cars were – Valiant was almost always ‘Valigrunt’ – and as I got older I kept thinking how the style of old cars just looked cooler and cooler.”

Mike was too young to drive during high school, but an older friend, Ken, had his probationary license and all-hours access to his mother’s car. The group of friends had always been roamers, and that carried over into long night drives when Ken got his license. “I remember driving with Ken on roads between small towns that had pretty high speed limits, driving through midnight fog and our visibility was so short that we sometimes turned off our headlights so we could see a little further,” he says. “It was really unsafe, but we were kids.

“We drove to the Longford gas plant and [would] sit on the hood of the car and watch the pilot flames burn and talk for hours. Doing that was always important to us. One night, when I wasn’t in the car, Ken was with three other friends and flipped the car and totalled it. Everyone survived, but it was pretty lucky everyone in the car was sub-6 feet because when it rolled onto the roof, the front completely caved in. Two years later we’d kind of gone our separate ways and the Longford gas plant exploded. It was a major incident here – two workers died and eight were injured. People in the state had no gas for two weeks. Selfishly, it felt like a full-stop on that part of my life.

* * *

It makes sense that these two threads – one that began with a terrifying travel guide, no less – would entangle themselves to become Dead Static Drive. There is freedom in a car, but also danger and isolation. The light of a gas station or a rest stop at the side of a darkened road can be as foreboding as it welcoming.

“I think that fear of a haunted house and fear of a rest stop might boil down to different explorations of the same theme, maybe? Fear of being alone and not knowing what might happen? I’m not sure,” he says. “I know that I feel a lot of fear from the grounded reality of a situation, and I remember being much more afraid in the Silent Hill games when I was in a real place like a hospital rather than the other-world places.

“I’m someone who lives in my head a lot. I don’t believe in a lot of the things that will scare me, but when I get in the zone and read or watch something really convincing then, for a moment I really feel some nervousness and panic and my heart races. And then I can return to normal afterwards fairly easily just by telling myself, ‘Well that was a good movie, obviously none of that is real,” and it’s a safe exit from all those feelings. I can’t speak for anyone else, but for me I think that ability to have a huge physical response in a safe way that’s exitable – that’s what I get out of horror.

“I also love weird fiction, too, and weird fiction often has an opposite effect on me. It’s usually not scary at the time and doesn’t raise my heart rate, but it is full of ideas that interest me and make me question what I actually know. Weird fiction often stays with me longer.

“So in Dead Static Drive, I’m hoping to have a bit of both – some parts will give a feeling of fear and some frightening moments, but be exitable. And others are going to be, hopefully, more intellectually interesting and present a few ideas that are less-scary but that make people ask questions long after the game has closed.”