Masquerada and the Heart of the Queer Family

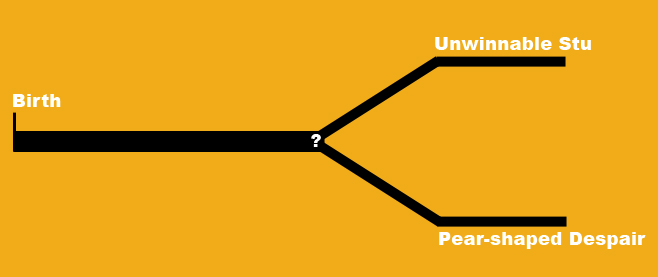

As gay people, we still have a lot of stigma and taboo to overcome. The idea that homosexuality is wrong permeates the fabric of this country’s society, and similarly draconian sentiments exist across the globe. But digging into why these taboos exist is worth exploring. The reason gay people – indeed, all queer people – are ostracized is because of the othering process. Because we’re different than the mold that society deems “normal”, then there must be something wrong with us. Much of this is codified in rules that become assumed morals for the population at large: Marriage is between a man and a woman. You can’t have sex before marriage. You can only truly love one person romantically. So much of the othering that takes place is centered around the formation of a family, a notion that has a narrow definition in the eyes of the status quo. Because of the nature of how queer people form families, they are ostracized. It also happens that video games, particularly party-based RPGs, are uniquely positioned to explore this dynamic.

Whether it’s the traditional nuclear family of the 1950s or the plentiful children of the modern evangelical movement, the ability to produce children is one of the hinges on which the othering of queer people turns on. There are other excuses, of course, but the lack of ability to have kids through sex with each other is a common refrain for why queer people aren’t treated as “normal”. When I came out to my father, one of the things he told me was the fact that I wasn’t going to have kids and carry on the family business. This is nonsense, of course. Gay people can have kids, whether it’s through adoption or a surrogate. But the idea of legacies is a strong one, and so many under the thrall of the status quo value blood legacies above all else, at least in my family’s case.

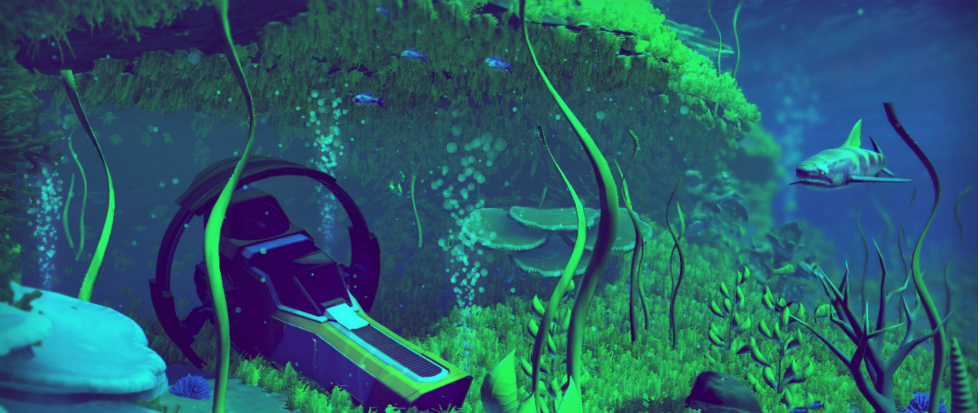

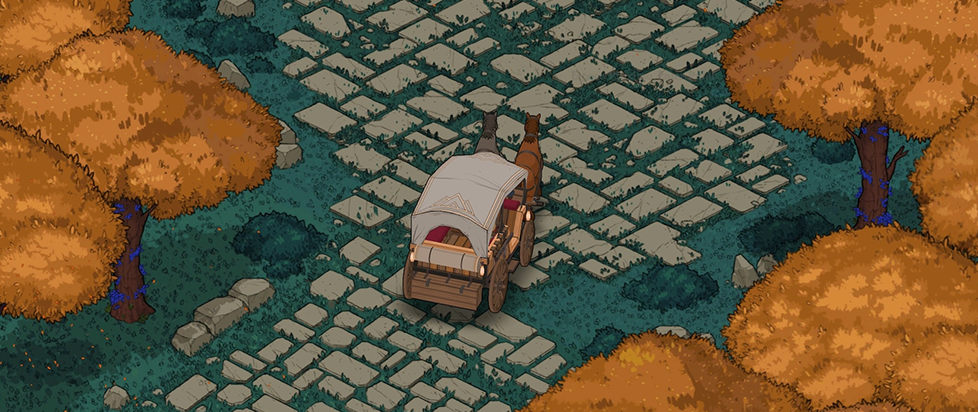

Portrayal of discrimination against gay people is often included in games that want to speak on that issue, but too often stops at the reason being that it goes against tradition. Masquerada: Songs and Shadows not only includes a gay party member, but structures its societal status quo to focus in on the familial angle of othering. Kalden’s backstory involves he future lover appearing at his door with a child in his arms looking for aid, which turns into a romance as they found an orphanage together. But the society of Ombre, the city in which the game takes place, values legacies as their connection to the past and way to the future. That doesn’t include adopted families, however, and gay people are shunned exactly because they can’t leave a proper legacy behind. But as we see in the game, Kalden found a family for himself, and his and his lover’s influence can clearly be seen in the kids they raise.

The game doesn’t delve deeper than that into exploring the nuances of the issue – the status quo still looms, but there exists people who will overlook it in favor of loving them regardless – but it does have more to say about found families. The party you belong to is a patchwork of people from different guilds with different agendas, yet they end up relying on each other and learning from Cicero, the de facto leader and your avatar in the game, and vice-versa. It becomes something of a family all its own, and not just to the in-game characters, but to the player as well. As you get to know them, learning about their troubles and becoming familiar with their personalities, you become attached to them, invested in seeing them succeed even through disagreements. It’s a compressed version of how improvised families form, sure, but it works as a model surprisingly well.

This idea isn’t unique to Masquerada by any stretch. Any competently written group of characters you find in a game has a chance of the player becoming attached. So many party-based RPGs give you this phenomenon to varying degrees of success, and though it’s always contrived by definition, it nonetheless imprints on you. By the end of the game, their legacy lives on in you. Masquerada hints at these themes through your interactions with your party, but also in the politics of the city at large, with the inter-guild interactions simulating, in a way, how adopted siblings would act with each other. By the end of the game, everyone needs to come together to battle an existential threat.

Again, this isn’t revolutionary by any means, but it illustrates how games can tackle the ideas of legacy and family, that what you leave behind isn’t always as important as being here now with the ones you choose to love. The queer experience is all too often about cobbling together a life in the shadow of a system that doesn’t want you to exist simply because you’re different. For us, family carries a deeper meaning than just blood, and RPGs, with their ragtag groups and long playtimes, allow us to grow close to people we want to spend time with in a world that’s hostile to us. In other words, an encapsulation of much of the queer experience both in the agony and joy of it.