The Unstable Sexuality of Joji

It’s 2018 and there’s a Japanese man laying under two women twerking over his face while singing about how women don’t find him desirable unless he is rich.

We have issues in America with identifying Asian men as hot, with viewing them as desirable figures. It isn’t simply a matter of lust, but a cultural swing towards the emasculation and desexualization of Asian men. There’s that old Grindr shorthand that may as well be cauterized into bathroom mirrors like whatever the opposite of a self-affirmation is – no fats, no femmes, no Asians.

It’s hardly a new preoccupation; the desexualization of Asian men has a complicated cultural history. Though there is a long history of seeing the East as “feminized” in relation to a “masculinized” West (read any text on Orientalism and the way in which Asian women are perceived as demure or subservient), that has not been the lone historical association towards Asian men. In an interview with Cristin Conger of Bitch Media, Amy Sueyoshi, the Associate Professor of Race and Resistance Studies and Sexuality Studies at San Francisco State University writes “In the 1930s, Filipino men are seen as having potent sexuality and stealing away all these white women who claim that Filipino men are actually better dancers than white men and better lovers.” Hypersexualization is not positive representation by any stretch of the imagination, but it seems counter to the current representation of asexual and impotent Asian men. However around the rise of modern US cinema, this stereotype has warped into something a bit more like what we see today.

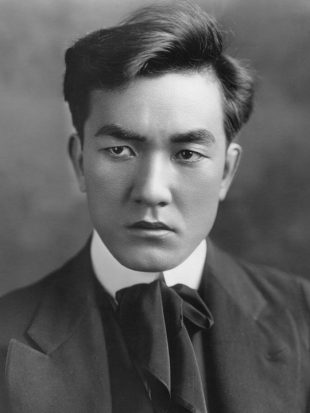

Sessue Hayakawa (circa 1915)

A lot of theorists and even modern actors today, blame the emasculation of Asian men in popular culture as a response to silent film heartthrob and Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa. Hayakawa’s success was entirely based in Hollywood, where he made high dollar amounts, apparently paid as much as other leading men of his time. Even when playing sexual aggressors (this was a thing in Hollywood in the silent film era, see any of the Sheik movies starring Rudolph Valentino as an aggressively sexual Arab man for whom consent is an abstract concept), he still maintained high box office crowds of his most “rabid fan base:” white women.

Hayakawa’s career was ultimately negatively affected by the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment around the second World War, but also by a direct response from Hollywood who seemed afraid of the sexual prowess of Asian performers which undermined perceptions of white sexual dominance. The blowback was intense.

In his text “Looking for My Penis,” Richard Fung writes:

Asian men, however – at least since Sessue Hayakawa, who made a Hollywood career in the 1920s of representing the Asian man as sexual threat – have been consigned to one of two categories: the egghead/wimp, or – in what may be analogous to the lotus blossom-dragon lady dichotomy – the kung fu master/ninja/samurai. He is sometimes dangerous, sometimes friendly, but almost always characterized by a desexualized Zen asceticism.

Asian men have been moved from heartthrob to nerd, even if the nerd stereotype is often portrayed as overtly lecherous, and even when it is not played by someone who is actually Asian (see the horrific performance of Mickey Rooney as Mr. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s). The rise of the Asian male nerd in 80’s film (Pretty in Pink) cemented the asexuality of the modern Asian man. In 2002’s party movie Van Wilder, we see Taj Badalandabad (played by Kal Penn) as a sexually repressed nerd who must be freed from his morals and introduced to sex by the wild Van Wilder. In the popular television show Big Bang Theory, we have Rajesh Ramayan “Raj” Koothrappali, who cannot speak to women outside of his family unless he is plied with alcohol. Even in movies ostensibly not comedies, the perception of Asian male asexuality persists. In the 2000 crime thriller Romeo Must Die, the scene where Jet Li kisses Aaliyah was reshot because it made the audience uncomfortable seeing an Asian man in a sexual light. In 2018’s Tomb Raider, the audience is given the perfect set up for a romantic duo between Lara Croft and her fellow adventurer Lu Ren – except nothing happens and they close out the movie as friends. In modern films and culture, it is difficult to find examples of Asian men who are shown as sexual.

In 2017, in response to a hateful Steve Harvey sketch on Asian men in the dating scene, Eddie Huang wrote a NYT op-ed entitled “Hey Steve Harvey, Who Said I Might Not Steal Your Girl?” In it he writes about a dominant culture that dismisses Asian male sexuality out of hand, “the one stereotype that I still mistakenly believe at the most inopportune bedroom moments…is that women don’t want Asian men. Attractiveness is a very haphazard dish that can’t be boiled down to height or skin color, but Asian men are told that regardless of what the idyllic mirepoix is or isn’t, we just don’t have the ingredients.” As he puts it, the structural emasculation of Asian men in popular media has led to actual real world consequences, towards the viewing or real men as undesirable because of their race.

It is within this historical and modern context that we find ourselves in 2018. This is the year of Crazy Rich Asians blasting through box offices with a romantic duo who are, in fact, Asian. It’s the year that K-Pop groups like BTS are making inroads into American households. These acts and performances function as anecdotes not a sign of a true cultural shift, but they’re still relevant towards the climate of today.

These last two years have seen a rising in the work of the label 88Rising. Specializing in Asian rappers and singers, they have been pivotal in the careers of acts like Rich Brian (formerly Rich Chigga), the Chinese rap group the Higher Bros and the R&B sensation Joji.

In the 88Rising label and accompanying acts, there are other more obvious acts of sexuality. Yaeji has a song where she talks about her decision to eschew condoms: “When the sweaty walls are banging/I don’t fuck with family planning.” Rich Brian is usually hit on in some way with Twitter exchanges asking to see his dick and songs where he talks about how he can now have sex with women because he’s 18: “Yeah, happy birthday to me/I’m 18 now/And women can legally have sex with me.” Indeed, in this stable of talented performers talking about their sex, Joji can seem like the least likely sexual icon – his songs are never explicit and his videos are often more contemplative than his contemporaries, even in a field of autobiographical hip hop performers.

Joji is the Japanese singer who has a video featuring his face being smashed by two twerking women. The song is “Yeah, Right.” In it, mumbling through his character’s depression, Joji intones “Yeah you bet I know that she ain’t/ Never give a single fuck about me/Yeah, you bet she know that we ain’t/ Never gonna be together, I see.” If anything the lyrical content seems to undercut the potential explicit content featured in this video – it is rare that you have a disinterested man being dry humped by two women on the face and think “Huh, no one is getting really anything out of this.”

“I’m kind of a prude with my lyrics” Joji says in the “Slow Dancing in the Dark” Verified video for Genius, and he’s not wrong. The lyrical content of his songs is fairly heavy on emotive crooning and light on explicit sexual acts. While Pink Guy, one of the characters preceding Joji, is explicit, Joji is subtler. “Slow Dancing in the Dark” could be about sex, but really only at a surface read. What the lyrics lack in explicit sexual content, they possess in a kind of emotional intimacy, albeit slightly warped, as though through a broken prism of someone who views sex and love as transactional and earned: “What you know about love/what you know about life/what you know about blood/bitch you ain’t even my type.”

It’s probably a bit important at this point to talk about the previous work Joji has done — in the form of viral, predominately YouTube based, characters Filthy Frank and Pink Guy. All three, Joji included, are the products of George Miller, a Japanese-Australian artist and musician. It’s a bit difficult to talk about Joji without mentioning them, even the Business Insider piece on 88Rising’s CEO Sean Miyashiro touches on the history of his viral fame (and infamy) – the Harlem Shake viral craze that got to the point where your local weather crew was doing it? That originated through the stylings of YouTube comedian Filthy Frank.

To put it frankly, Filthy Frank is disgusting. He (and the pink-leotarded Pink Guy) are offensive, loud and at least a touch appalling to common decency. They are designed that way. In an interview with Pigeons and Planes, he says: “That’s all part of the fun, getting emails from disgusted parents and stuff. That’s part of why I do it.” That you would somehow get from these two Internet memelords to the soft spoken grandeur of a song like Joji’s “demons” is surprising. That Joji quit his comedy act, citing ill health and a changing taste, is less surprising.

When discussing sexuality and the modern incarnation of Joji, Pink Guy – whose album Pink Season came out in 2017 – is particularly relevant.

In the 88rising video “Joji & Lil Yachty Have Curious Conversations,” before telling Lil Yachty about the erotic explorations he can experience at Soapland, they have a discussion about Pink Guy:

Joji: “I’ll be rapping about a character who likes to suck dick.”

Lil Yachty: “He’s gay?”

Joji: “He’s not gay. He’s just a sexual being.”

As opposed to the stated prudishness of Joji, Pink Guy is oppositional in terms of sexuality. He’s a sexual being – in the “STFU” video he humps a wildly spraying water hose between pranks and yelling that no one cares whether you’re alive, and this is hardly the exception to the rule. Take the abrasive song “She’s So Nice,” a screaming, near unlistenable rant from a pink suited sexually charged demigod where he explains that he has fucked your fat whale of a girlfriend because he wanted to, because he could and because he wanted you to taste his dick when you went down on her next. It’s crass, aggressive and lewd, an anthem for desperate sex between desperate people who view intimacy as a competition.

At the same time, the song feels like a duet between two alternate swinging ends of this persona – the abrasive rage of Pink Guy, with a soft spoken, mumbly chorus where the singer intones “She’s so nice/she’s so nice/she lets me use her body/but she’s so nice.” It’s a harsh juxtaposition, one a Rap Genius commentor might call a riff on Drake, but which reads like an interior conversation between two disparate personalities. It’s little wonder that fans have identified this softer voiced character as Joji.

Don’t let the hook fool you, this softer character doesn’t love women any more than Pink Guy, his distrust of them is just buried in a repeated refrain that she’s nice before finally settling: “I treat her badly/but she comes back every time/it goes to show/none of these hoes/are worth a dime.” He’s a sad, sexual, softboy – a fuckboy who goes for emotions, even if at the end of the day he has the same intentions. He may not be shrieking about fucking a girls titties, but the quieter dude is no less dismissive of a woman’s worth. Women in Pink Guy’s songs are of this type, disposable, detailed only in their failures and willingness to have sex with the man George Miller plays. This continues to play out in Joji’s works today.

That sexual sad boy isn’t dead, he’s alive in the videos for more modern incarnations of Joji, including “will he,” where Joji lays in tub of blood near a woman shot through the head by Cupid’s arrow. The video starts off with a panda suited figure dancing in the most melancholic version of Fiona Apple’s “Criminal” house, signs of a past nights partying running counter to the images of Joji walking down the street in a blood stained shirt. It’s imagery that’s used again in Jojis video for “Slow Dancing in the Dark” where he plays a faun like creature in a white tuxedo stumbling down the street, similarly pinned by Cupid’s arrow in a manner that seems fatal. There’s a sense of violence, a question of sanity and health, that is a part of most of Joji’s current works. Love, to this character, is a violent affair. But it’s still a form of romance, that kind of R&B sensuality that is pulsated by promises of something ill and formless out of the corner of your eye (The Weeknd’s “The Hills” video comes to mind as something similar), a modern Bret Easton Ellis adaptation of malaise and interpersonal misery.

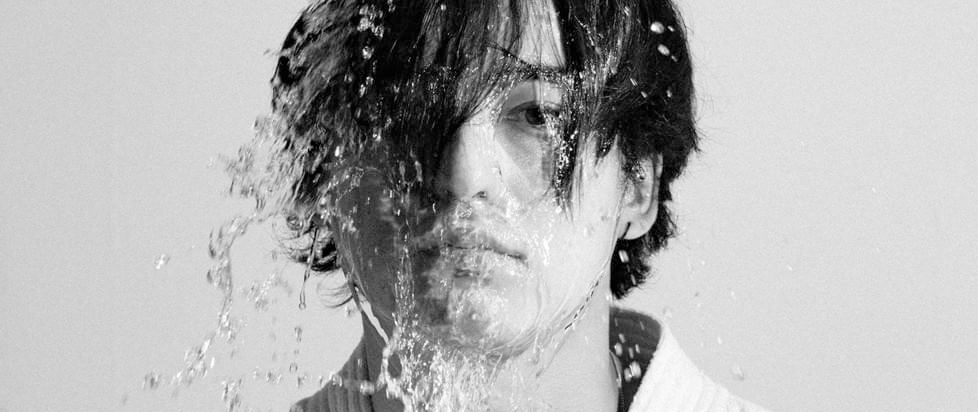

“If you’re like an ugly, not a great looking dude, you know that like a chick is spending all this time with you because you got money or whatever. It’s that point of self hatred that you don’t mind,” Joji explained in his video for Genius. But he isn’t an ugly man. He’s got a dangerous sort of attraction, a wild romanticism that calls out for attention in ways that the standard Asian male stereotype isn’t necessarily ready to handle. Desexualized Joji is not.

It’s difficult to quantify attractiveness, since it’s so specific, but in the spirit of clarity: Joji’s energy is firmly in the realm of “don’t stick your dick in crazy,” a person who it would probably be a bad idea to sleep with for any number of reasons but which you may do anyway. There’s this kind of instability to the character, but at the same time a sort of intensity that builds into a kind of intoxication, this feeling that for this kind of guy you’d be the center of his universe in the worst possible way. It’s a disturbing kind of sensuality, a kind of uneven stance where you don’t know where you stand or how you stand, but maybe that’s the appeal. He’s that toxic kind of love that you have when you’re young and before you know better, the kind of boy you break up with and then he takes a long distance bike ride across the country to avoid being in the same city as you. The kind of guy to shave his head cause he sees you with another man.

It’s 2018 and Joji is rollerskating down a New York City street with roses in hand.