What Time Loops Mean to Me

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #172. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

What’s left when we’ve moved on.

———

I get déjà vu a lot. Semi-frequently I find myself standing in front of the produce aisle looking at a crate of apples I swear I saw in a dream. When someone finishes a sentence, I’ll sometimes get the feeling I could predict what they’re about to say. As I understand it, the science behind déjà vu is that it’s basically a brain fart, not a predictive vision. Still, whenever it happens, I have a moment of thinking, as I’m sure everyone has, what if I’ve been here before?

As someone prone to this line of thinking, it seems natural that I like time loop stories. However, time loops can be difficult to love. Like time travel, time loops have a lot of fiddly details (do characters retain their memories? Do the time loop selves live after their loops end?). Personally, I don’t have patience for much beyond the basic formula of “you’re stuck in time, and you need to do something about it.” They are repetitive by definition, which is something that can also be frustrating.

And yet, time loops have been a Thing for a while now in all kinds of media, and particularly in games. The late 2010s were an inflection point in the genre: Outer Wilds, Minit and Elsinore all released within a year of each other. Since then, there’s been Loop Hero, Twelve Minutes and the mod-to-game The Forgotten City to name just a few. These games constitute two categories of time loop games: those which treat it as a mechanical device, like a temporal metroidvania where each loop gives you new abilities, and those which treat it as a narrative experience. Of course, there are games that do both, like Majora’s Mask, where the process of time looping is a gameplay tool as well as a key part of the story.

2023 wasn’t as big a year for time loop games as, for example, 2019. But the games that came out last year represent a tipping of the scales toward the narrative extreme, where characters’ interior feelings about being in a time loop come out. For example, Slay the Princess, which launched at the end of the year, has its Hero remember his past actions, which understandably causes some trauma. It brings up an important aspect of time loops as a concept: viewed more deeply, they’re pretty disturbing.

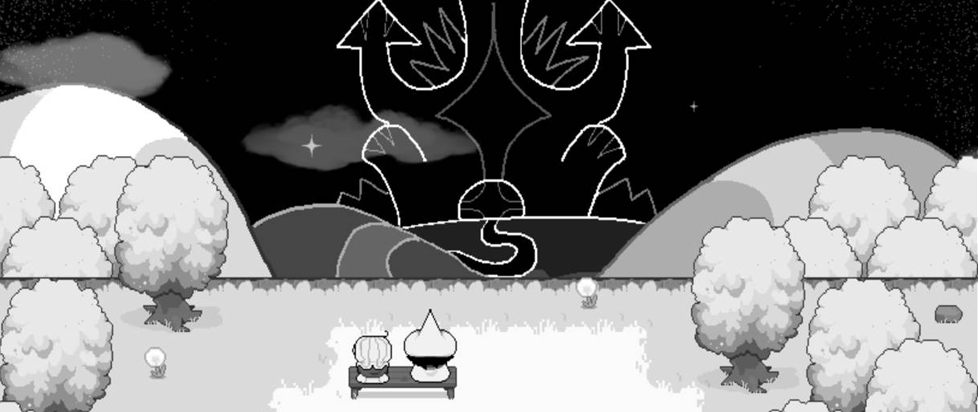

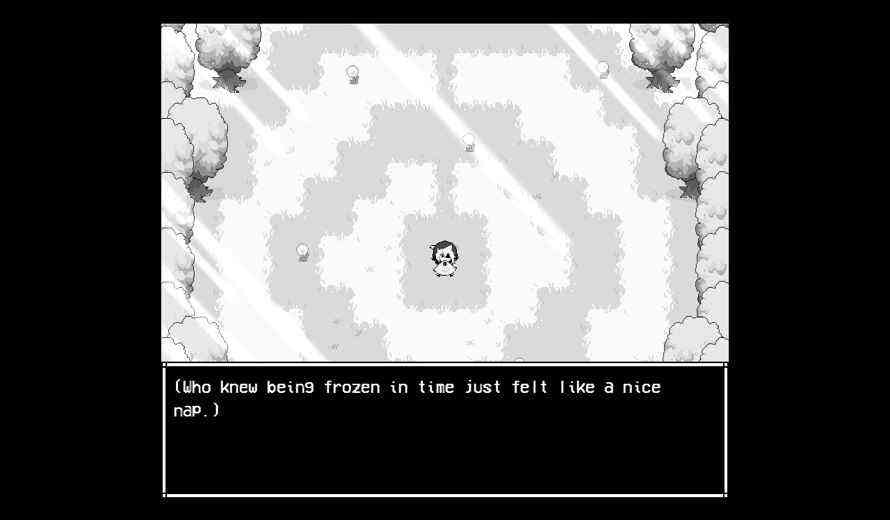

This was a theme echoed in another time loop game of 2023: In Stars and Time, an RPG where the protagonist Siffrin gets trapped trying to kill an evil king over and over. The game starts at the end of an adventure; your whole experience is going through a final dungeon, the House of Change, figuring out how to progress and maybe, this time, beat the final boss. Of course, this ends up being more complicated than you’d expect; where I thought I’d go through ten or fewer loops, I went through dozens, each one going slightly more wrong than the last.

The game’s creator Adrienne Bazir agrees that time loops have an underexplored sinister side. “I’m a big fan of time loop and time travel stories in general,” she told me over email. “But in most of the media that I’ve personally seen, time loop and time travel are used as means for the story to somehow get somewhere, and don’t necessarily go deep into how horrifying those would be.” Siffrin themself slips into hopelessness over the course of the game, isolating themselves from their friends and refusing to tell them about the time loops (this game’s lesson: be emotionally vulnerable with your friends!). Of course, Siffrin’s friends notice something’s up before long and there’s a race against the clock to figure it out, which brings its own difficulties.

Bazir sells the relationship between these characters through a lot of writing. While there is repetition in the dialogue, most events have at least two or three variations depending on how many times you’ve seen them, what you’ve done in the loop so far, and what items you have. “I had so much fun writing all those variations, and how those variations shape the character of Siffrin and their party members,” Bazir said. “Seeing how all those characters react to those small changes helps the player figure out what kind of people they are! Really, time loops are a great way to do character studies, which are my favorite part of writing.”

Aside from being windows into characters, time loops can also offer a way of making videogame systems feel more integrated. Bazir identified systems like game overs, new game + and even saves as things that time loops are uniquely suited to represent. This utility is present in non-digital games, too. I asked Max Kämmerer, the creator of What’s so cool about time loops?, a hack of the system What’s so cool about outer space?, what he felt time loops offered TTRPG players. “What I like about the idea of time loops is that the characters and players gain knowledge that they can use in the next iteration and in the end to create kind of a perfect iteration when they essentially solved the puzzle of the loop,” he said.

Overcoming obstacles and learning from them is a major theme of What’s so cool about time loops?. Sample scenarios include an alien invasion, the last day of a war and an awkward family dinner. After you create your own time loop, you try to “solve” it again and again. At first, players might know things about the world that their characters don’t; however, after a few loops they’ll begin to wise up. This process of gaining more knowledge corresponds with the process in other RPGs of leveling up and growing stronger. Like puzzle games, you’re dependent on your mind rather than your stats.

Kämmerer also noted the freedom time loops can offer players to make mistakes without lasting consequences, or in spite of them. “I like systems that let the players ‘fail forward’ or ‘succeed at a cost.’ The player may fail a roll but still get what they want, it just comes with a problem or other disadvantage. Time loops are also kind of like that, by failing something during the first iteration, even with very bad consequences, the characters learn something about the world or situation to use in the future.”

One danger of time loop games is that they become boring for the player. I had this experience when I tried Outer Wilds, whose freedom of exploration couldn’t make up for all the running back and forth I needed to do. In Stars and Time faced the same problem. Since the whole game involves repeating the same maps and conversations, letting players skip dialogue and travel to particular places in the dungeon at will was especially important. However, Bazir wanted to avoid making a playthrough too smooth. After all, Siffrin’s experience of the time loops is far from seamless: while they feel invulnerable at first, the process of having experiences with their friends that only they can remember eventually wears them down, to the point where each new loop becomes painful. “The player should feel that the game is repetitive, or boring, or even infuriating, because that’s how Siffrin feels.”

These conversations helped me to realize what I find most interesting about time loop games is that they give me the opportunity to grow alongside the character. When little about my external environment changes, I’m forced to look inward and use my brain, and my memories, to find out where to go next. As many of these games demonstrate, that growth can sometimes be quite painful. Yet, the way mechanics and stories combine provides a nice metaphor for the experience of struggling through something you’re not the best at, but that you’re obliged to keep trying again and again.

Bazir sees those more painful moments as almost therapeutic. “Of course, we can’t experience a time loop in real life, but a lot of us do feel similar emotions to those narratives. The routine of a 9-5, an endless job, the solitude of working from home, feeling removed from society, having difficulty communicating with loved ones . . . Those are feelings that most people have gone through in one way or another, and being able to experience those in a game with magic and fantasy in it is very beneficial, I think.”

———

Emily Price is a freelance writer and PhD candidate in literature based in Brooklyn, NY.