On Gremlin-tology

This is a feature story from Unwinnable Monthly #158. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

We all know about gremlins, right? Even among those who haven’t seen Joe Dante’s 1984 movie, Gremlins, there’s an understanding that gremlins are little creatures that muck up the works, right? Of course, we don’t all know but gremlins have been around long enough that the little monsters have penetrated our cultural-historical memory. I say, “long enough” because we’re perhaps only a generation or two removed from a time before anyone anywhere could point to something and say, “that’s a gremlin.” So please, allow me to take us on a journey into what is a gremlin, where they came from and where they might go.

As always, my preference for themes for theme issues is to keep them high level, abstract, able to be attacked from multiple angles and in multiple ways. But of course, people want to know, what does the theme mean? To start to answer the question I’d say gremlins are “the little monsters that imperceivably foil you. Or perceivably so.” As humans, we like to have answers as to why. Why did my brand-new air fryer work only once? Why did my car just sputter and stop? Why did that airplane go down for seemingly no reason? Gremlins.

Of course, there are better answers. That air fryer was a cheap piece of junk off the line. That car badly needed an oil change. And most worryingly, basically any number of things can go wrong in the sky. Planes are finicky things that need dozens of things to plan simultaneously to keep everything flying. Sometimes, that doesn’t happen. But in those moments, we, like the airmen who popularized the term “gremlin,” need to pin the blame on something, offer some kind of definition that is pointed if less reasonable than “stuff happens.”

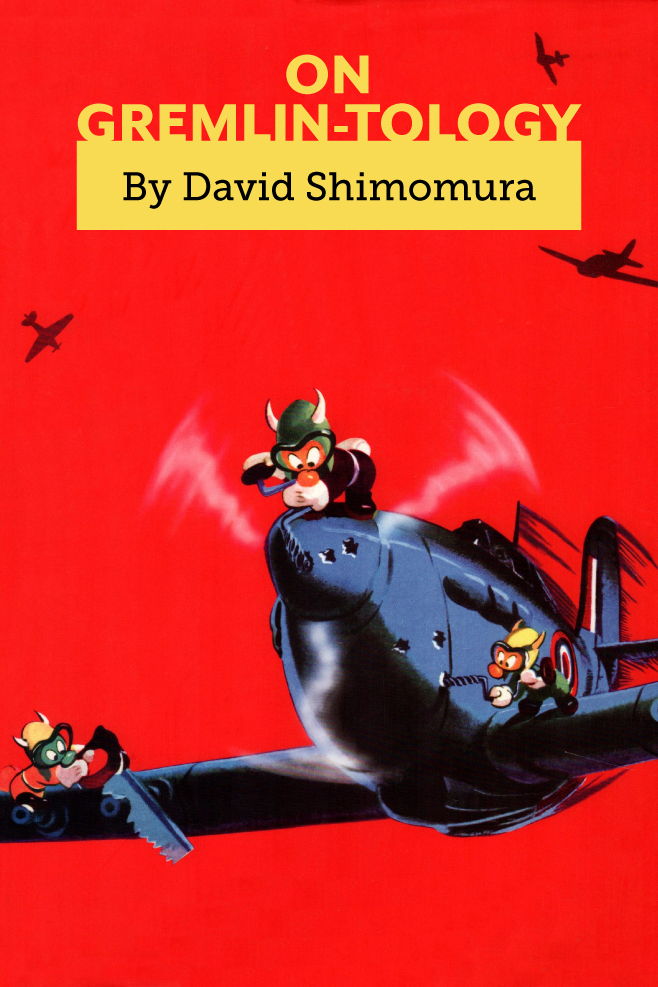

Gremlins as a definable phenomenon are shockingly new and came about quickly. “Aviation” as we think of it today had only existed for 40 years before pilots, mechanics and even the government openly acknowledged them. But this process is natural. It happens when humans, simple as we are, bump up against a new frontier. As we pushed outward into the “wilderness” of the woods and seas we found all manner of creature to answer our questions. The gremlin was simply the next one to find, we’d scoured the earth, mapped it to the poles and back, but now we’d found ourselves in the skies.

Even by modern standards, the closest we’ve gotten recently is perhaps Slender Man, an entirely invented figure who leaked out of his corner of the internet and has become a pop culture icon. Strangely, Slender Man also seems to be on the same 40-year timeline as gremlins were. But the key difference between them is that gremlins, while equally fictional, offer an explanation, not just a fright. We’ve long been creating boogiemen to keep us in line but explaining the unexplainable is the real of far more ancient and powerful things.

And naturally, there are better answers. Pilot error, mechanic error, factory faults, lightning, geese. All of these things were much more likely to be the cause of the strange and inexplicable incidents in the skies. But human error was not satisfactory. Worse, it meant that dangerous, life-threatening errors were being made with regularity. Surely then, it was the fault of some opportunistic rogues we’d provoked by taking to the skies.

In this way, gremlins aren’t just monsters that foil one’s best laid plans. They’re a handwave that our best laid plans are not so well laid. As creatures of an increasingly industrial, mechanical and automated age they remind us insidiously that humans are not the masters of our world we think ourselves to be. As we sought to conquer that last frontier, they were there to remind us that ultimately, we are not as mighty as we might think ourselves to be.

This kind of mythological scapegoating is certainly novel, if not new. Many of the other folkloric figures that answer the answerable tend to not do so in a manner that handwaves the obvious human errors at play. But this makes gremlins an especially beautiful creation of humankind. We made them not to feel better about the natural world, but instead to feel better about the reality where we are not especially good at things.

Strangely, there seems to be some level of denialism or revisionism as to this lack of ancient quality. While not exactly modern, gremlins in other media seem to be cut from a much more ancient cloth. Roald Dahl’s Some Time Never: A Fable for Supermen show them to be quiet ancient, maintaining dominion over the earth long before humans. They’re encounterable in Dwarf Fortress, a totally fantasy setting with relatively little machinery. And of course, in the eponymous film, they’re the cast offs of the especially ancient mogwai.

Instead of reckoning with our fallibility, we’ve further entrenched gremlins into the collective human myth. We could say, “Oh yes, it was very weird and strange when we invented monsters so we didn’t have to admit we made crappy airplanes.” Instead, we invented monsters and found ways to perpetuate them. Maybe this is the ultimate gremlin act. As we’ve built more and more systems of increasing fragility, we’ve invented a new frontier for gremlins to wreak havoc in our lives. Some small error somewhere along the pathways and pipelines of the internet could keep you from reading this, from it being delivered, or even correctly uploaded. Someone, somewhere, yawning through their workday could easily introduce the tinniest error that brings the dozens of services needed to facilitate your reading this. But no, it isn’t that person, it’s a gremlin.

And of course, as we see a new generation of people rising positions of power, we see the beginnings of the weaponization of gremlins. Why admit that you are actively ruining a company when you can blame Twitter for its own failures? Why admit to eroding democracy when you can create conditions for its erosion over time? And when the dams break and it’s too late surely the explanations will not be that human choices were made. Surely, we’ll hear that unforeseen forces acted to bring about ruin. It was the gremlins. It had to be.

So yes, gremlins are those little creatures who lurk and make things worse. But unlike the true monsters, gremlins have art. They have music, and dance and society. Gremlins are people. Accidental or purposeful antagonists whose actions set about a chain of events read at the end as “inexplicable” all the while being entirely explicable. And funnily, to find a gremlin is to eradicate it. To know that we were always the engineers of our own folly is to admit there was never a gremlin. Except, well, we’d have to do that first.

———

David Shimomura is the editor in chief of Unwinnable. Follow him on Instagram and Twitter @UnwinnableDavid.