My Own Personal 25th Universe

I’m not an expert on John Calhoun, or psychology, or any of the sciences tangential to the famous “universe 25” experiment. But when I read about it for the first time a few days ago, it made a sudden, comforting and convenient kind of sense, whereby something that I’d previously thought was just me – and that even though I believed, and believed it was accurate and fair, I would never be able to describe to other people because it would make me look all paranoid and cynical and unfair – there was actually this perfect scientific illustration for, i.e. the universe 25 experiment expresses and incarnates, starkly and exactly, this complex and abstract kind of hypothesis I’ve had for a while, and becomes the paper bag I can use to assuage the ugliness of my personal opinions.

I don’t have an ideology but my unifying theory of games and what’s wrong with games, and what’s the problem with playing games, is that escapism is essentially in myriad emotional and spiritual ways very bad for you. I feel like in videogames, we have somehow, as an entire culture, decided and continually celebrated and reinstantiated the idea that what games should do is provide an escape, a distraction or, in some cases, a complete replacement for real life. In the 1990s, when I was growing up and playing games in a significant way for the first time, it was like every cultural force outside of games – the media, politics, health system, education, institution of the family – was against games on the grounds that they stole young people away, for inordinate amounts of time, from the things that genuinely mattered, and that videogames responded with a united kind of venom – in DOOM, Mortal Kombat, Carmageddon and the first Grand Theft Auto, it’s like games were content, and actively trying, to live down to social expectations, and playing them and using them for escapism was positioned as a kind of iconoclastic rejection of authority. Games were low, and in poor taste, and bad for you, and that was the point. Games weren’t just a way of escaping reality. Playing and owning and liking games signaled a kind of minor personal rebellion against what society thought was decent – escapism, yes, but escapism with a kind of anti-social, anti-propriety intent.

And now, games seem very determined to be accepted and loved and taken seriously by everybody, and for the large part, as a culture, as much as they can be described as a singular intelligence and entity, have decided that the thing they can do, that will get them accepted, is provide escapism beyond movies, TV or books, and so the provision of that escapism has become the like general goal of games, as a culture. And also this escapism is not offered by way of saying to general ideas of taste or what you should do with your life that you just aren’t interested – games don’t provide escapism iconoclastically, so that you may play them as a means of signaling that you are angry with society, and social standards of properness. Games now seem to offer escapism as a kind of assisted suicide from reality, not to drop out from society and its standards and in doing so make a point about your feelings towards society and its standards, via that dropping out, but simply to opt out, to ignore, leave, have nothing to do with, hide from.

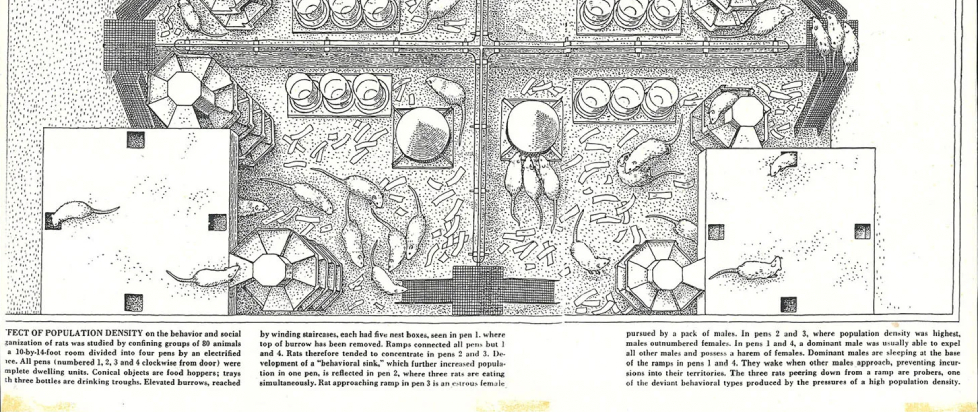

Like the rats in Calhoun’s experiment, who after four years of being given as much food, water and comfort as they would ever need, went insane, the total escapism offered by videogames today – the opportunity, if you play enough of them, for a sufficient amount of hours – to more or less not just escape from reality, but replace it, with a reality entirely non-confrontational and kind to you at all times, can and probably already has driven me to some kind of spiritual death. The big videogames, now, are more or less infinite, and there is a much reduced social stigma attached to occupying the entirety of your free time with playing them – a lot of people who do this are in fact very successful and rich. I think my ability to properly comprehend and manage my emotions impelled by the world around me has been impacted by the time I have spent not even playing but like living inside videogames. I have become less interested in other people’s problems, more self-obsessed and deluded with regards to the cosmic ratio of good actions versus good outcomes – games have misled me to believe that reality, as in videogames, where I have spent probably a cumulative several years of my life, I deserve and will receive good for doing, acting and thinking good, such as the simple, twee and escapist nature of intra-videogame morality. And I’m liable to become angry, or upset, when confronted with the fact that this is not the case, and then possibly retreat back into a videogame.

Which will be the focus of this column, the emotional, psychological circuit catalyzed by videogames, and its inevitable dead end.

Edward Smith is a writer from the UK who co-edits Bullet Points Monthly