Noteworthy Hip Hop – A Kendrick Lamar Retrospective

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #152. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Selections of noteworthy hip hop.

———

Since 2010, I’ve spent a lot of my time listening to all sorts of hip hop, and I’ve heard things you people wouldn’t believe. Odd Future open for Kid Cudi at Red Rocks. I watched Spark Master Tape glitter in the dark, nearly breaking the surface of the underground, only to be lost, like tears in the rain. Well, to be honest, you good folks probably would very much believe those things. But I also saw something more exciting over the last 12 years or so – the rise of Kendrick Lamar.

While of course there is debate about whether he is the best rapper of his generation. He is certainly among the list and, while not the bestselling rapper of the 2010s (somehow, Drake can never be caught), his albums are certainly among the most critically celebrated and certainly sell better than most. So, in honor of his most recent album’s release, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers and the ten-year anniversary issue of Unwinnable, I wanted to spend some time reflecting on Mr. Lamar’s career over the 2010s and think a little bit about what it appeals to me so much.

Like me, Kendrick Lamar was born in the late 80s, but that’s pretty much where the similarities stop. I’m a white guy from the plains of the Midwest and Kendrick is a Black man from Compton, home to the g-funk, west coast gangsta rap that rose to dominate much of the late 90s and early 00s hip hop. In that milieux, Kendrick began honing his craft in the early-2000s, eventually releasing a series of mixtapes under his nickname K.Dot (which, to be honest, I’m not super familiar with) and finally breaking out of the mix with his last mixtape, Overly Dedicated in 2010. Coincidentally, this was the same year a fresh-faced Stu Horvath founded the now classic underground gaming magazine, Unwinnable.

It was also the year I first started running into Kendrick Lamar’s name, popping up on forums as a young up-and-comer. However, as with too many rappers, I just kind of moved along and didn’t start digging into his work. Instead, it took his next project, 2011’s Section .80 to drop for me to take notice of Kendrick’s output. To be clear, as soon as I heard those first lines off of Section .80, the pitched-down voice calling everyone to “gather ‘round” and invoking the refrain, “fuck your ethnicity,” I was hooked. Nearly every track on Kendrick’s debut was thoughtful and fun, bringing together my favorite combination of hip hop music, conscious lyrics with a catchy hook and beat. The pinnacle of this combination of course appears on the final track, “HiiiPoWeR,” produced by J. Cole, which weaves the names of murdered Black leaders into a renewed call for unity. To this day, “HiiiPoWeR” remains my favorite Kendrick song. It has leaked into my brain to such an extent that I rarely spend a week without a line echoing in my head.

The next year, Kendrick signed with the godfather of the West Coast, Dr. Dre and Aftermath Records, and dropped what appeared to be his magnum opus, good kid, m.A.A.d. city (GKMC). Across this sprawling album, Kendrick takes us on a story from his youth in Compton, told from the window of his mom’s borrowed van. In the midst of chasing girls and smoking weed laced with cocaine, Kendrick gets pulled into a breaking-and-entering, which ends up with one of his compatriots getting shot and dying. The nonlinear story is interlaced with skits, voicemails from his mom asking where her van is (and his dad asking about his damn dominos), and a thoughtful prayer. In the end, Kendrick arrives victorious into the contemporary Compton, a survivor of his youth in a dangerous city.

Meanwhile, I was spending most of my time at nearly the same age as Kendrick in Boulder, Colorado, working on my magnum opus – my dissertation about Reddit. Don’t go read it. But, GKMC was a primary soundtrack throughout that writing process, resonating in the background of my reading and research, plugging my brain into another part of the American process that was viscerally grounded in a reality I never experienced. And by the time I was finished with my dissertation three years later, Kendrick dropped his second classic. I really needed to rethink what I was doing with my life. I needed to go outside and touch grass, as the youth say.

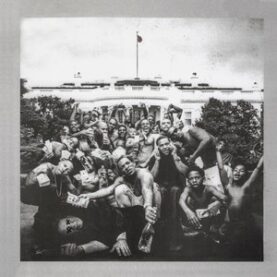

To Pimp a Butterfly (TPAB) dropped in March of 2015, only two months before I defended my dissertation. As almost everyone is now aware, TPAB has become one of the most celebrated hip hop albums of all time. It is a tribute to Black America, a criticism of the structures that created it and a call to arms for people to rise up to defend it. Looking back on it, seven years later, the only criticism I can come up with is that it feels, in many ways, like the epitome of Obama-era politics. Despite the bleakness of many of the songs on the album, there’s a hope – there’s an optimism. Yes, America pimped Kendrick’s metaphorical butterfly, exploiting him like they did Tupac and so many Black artists before them, but there is light at the end of the tunnel. The butterfly has wings – the butterfly can fly. Just like I flew when I graduated with a PhD! Flew right into unemployment and diabetes. Listen, 30 was a rough year for me.

To be fair though, 2016 was a rough year for most everybody I know. We can all remember that shit show, so I don’t think I need to spend too much time rehashing that bullshit. Kendrick released an album that year too, essentially the b-side to TPAB, Untitled Unmastered. Like 2016 at large, I won’t spend too much time on this one, except to say even Kendrick’s b-sides are worth a listen.

* * *

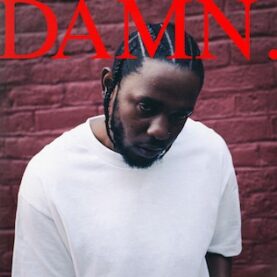

By 2017, I had started a new job and moved to Boston. I was starting back at the beginning, starting to work my way up through the academic publishing mines and starting to read this underground gaming magazine, Unwinnable. Meanwhile, Kendrick was busy earning a Pulitzer Prize with his fourth album, DAMN. As much of a feat as earning a Pulitzer Prize is (especially for a hip hop album), I’m actually more impressed that for the fourth time in a row, Kendrick somehow managed to make something that sounded new, relevant, thoughtful and enjoyable. He managed something that very few rappers, musicians or just artists in general are able to do. With DAMN. Kendrick showed that he had longevity and the ability to switch things up and not get stale, partly (I think) because the Obama-era politics of hope was over. DAMN. certainly feels more cynical than his earlier work, starting out with an attack on Fox News, peaking with a call for humility from his perch at the height of his clout and with no satisfying conclusion about where we are going. Instead, Kendrick is dwelling on the past, about his father, about depression, survival and the potential of dying in a gunfight. Well, that is if you play it from front to back.

Looking back, 2017-2018 may have been the apex popularity of Kendrick’s career. I mean, I wouldn’t stand by that in a matter of life and death, but it’s definitely arguable that between winning a Pulitzer and then crafting the soundtrack to Black Panther in 2018, Kendrick had never had a wider audience. While less personal and less political than his earlier work, Black Panther soundtrack is still a remarkable feat, bringing together Swedish composer Ludwig Göransson with some of the luminaries from the hip hop world including Vince Staples, The Weeknd and SZA. I’m not sure there will ever be a soundtrack that can match this album, and in a rare move, I’ll give Marvel some props for letting Kendrick and Ryan Coogler take control of this project.

In 2018, Kendrick reached his widest audience yet, and so did I, when I published my first article for Unwinnable! It was a little Exploits meta piece about the potential influence of Stalker on Annihilation, which got me called an “arrogant ass” on Twitter by a certain science fiction author who shall remain nameless. But I’m still pretty proud of this one, even if someone got pissy. Not long after that piece, I began writing more regularly for Unwinnable and then, in 2019, began this column and I started pumping out that content on the regular. Meanwhile, after releasing five albums in eight years, it seemed like Kendrick was going to take a break. As he wrote in 2021, he would go months without a phone, keeping silent. I kept writing about other hip hop albums, just waiting for the day that Kung Fu Kenny might come back to bless us with his next masterpiece.

Then, suddenly this spring, there was hope. He announced Mr. Morales & the Big Steppers (MM&BS). Would this be yet another classic by an insurmountable artist, who despite having not dropped a solo album in five years was still revered as one of the best in the game? Well, as are most things in the post-truth era, it really depends on who you ask. If you look at Twitter, it seems like some people think this is better than TPAB and DAMN. combined while others think this is just a terrible turn in his work. Polarizing, I think, is what we call something like that. Critics seem to be a bit more unified, at least, seeing this as yet another solid entry in Kendrick’s oeuvre. I tend to agree. While I think it’s not quite as conceptually brilliant as TAPB and GKMC, Kendrick’s newest effort is far from a flop. It’s emotional, thoughtful, sonically ambitious without sounding like it will be dated in two years – a personal reflection on fatherhood, his relationship with his fiancée and with his fans, and his place in the world. Kendrick is reminding his fans that he is a person, with flaws and all, trying to live. He is not your savior.

Like Kendrick, I also am a relatively new father and finding my flaws are more on display than ever – especially the flaws in my writing (I think I’ve made a very similar Blade Runner reference somewhere in this column before). But I also find that there is something about Kendrick’s music, from Section .80 to MM&BS, that helps me understand his creative processes. It might have something to do with being contemporaries. I see some aspects of his growth experience in myself, but he forces me to see the difference too. We may have both been born into the Ronald Regan era of the US, but I can never fully comprehend his world. His art is the only access point for me. His music makes me face my own limited, bourgeois, white pleasures. Yes, I feel kinship with Kendrick, but it’s refracted — a voyeuristic, parasocial kinship only capable of being framed through my whiteness. But even so, through his writing, through his poetry, I do feel it. I feel like I can understand what drove him to make this music, and I sense my own subjectivity in it.

So, in 2022, Kendrick and I still stand apart for many reasons, but I stay connected to his world. And maybe, if when Kendrick broke onto the mainstream back in 2010, he also started reading a small but plucky gaming magazine, he stays connected to my world too. I mean, I doubt it, but I can always dream.

———

Noah Springer is a writer and editor based in St. Louis. You can follow him on Twitter @noahjspringer.