Boston is Burning!

Justin Reeve, fire safety correspondent

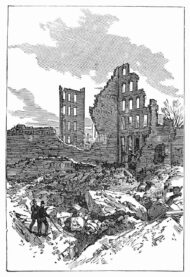

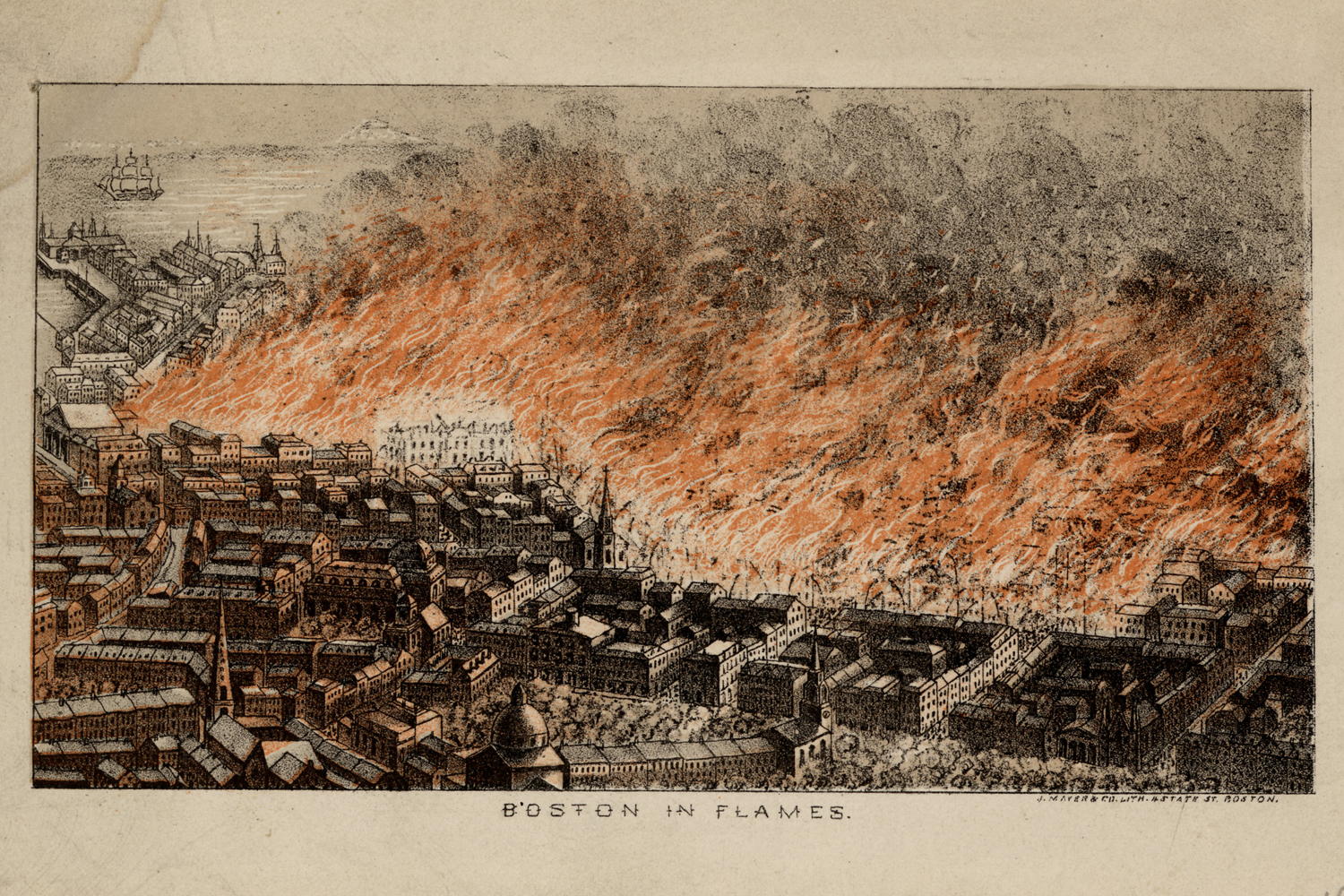

We suffered one of the biggest losses in the history of our nation earlier this year. I’m talking of course about the Great Fire of Boston. Starting on the evening of November 9, the fire soon spread across downtown Boston, reducing more than 60 acres of real estate to rubble, taking a total of 30 lives including 12 firefighters and causing over $70 million dollars in property damage. Well over 750 buildings burned down in the blaze. But the news isn’t all bad. The disaster might just prove to be a seed of change.

There were several causes behind the fire in Boston. The construction codes for example have never been strictly enforced, resulting in extremely narrow streets among numerous other infractions. Many of the structures were too tall to reach by fire ladder and there wasn’t enough water pressure in the fire hoses to put out the flames on some of the rooftops. These were mostly made from wood, so even in cases where the walls were brick, the fire could easily spread between buildings. The fact that warehouses commonly contained combustible materials on their upper stories only made matters worse. The situation was further aggravated by the fact that all of the fire alarms in the city were kept under lock and key to prevent false alerts. Boston has a very sophisticated system which notifies the authorities by telegraph whenever a fire alarm is activated, but only a couple of people were able to unlock their protective boxes, rendering them almost completely useless. The city also has nowhere near enough fire hydrants, even today.

The fire broke out in the basement of a warehouse on the corner of Kingston and Summer Streets. The blaze quickly spread to the elevator shaft in the center of this building, causing the dry goods on the upper stories to burst into flames. The roof caught fire shortly afterwards and the flames were able to spread in between buildings with incredible speed. The blaze become so intense that even brick walls weren’t able to withstand the heat. The fire tore through downtown Boston for nearly an hour before the authorities were notified, but even after they began dousing the flames, firefighters had a hard time finding fire hydrants that could supply enough pressure to reach the rooftops. There were attempts to create a firebreak by using explosives to demolish buildings that were standing in the way of the blaze, but the measure wound up doing more harm than good as flaming material went flying off in all directions. While the fire was eventually brought under control, the blaze could more accurately be said to have burnt itself out.

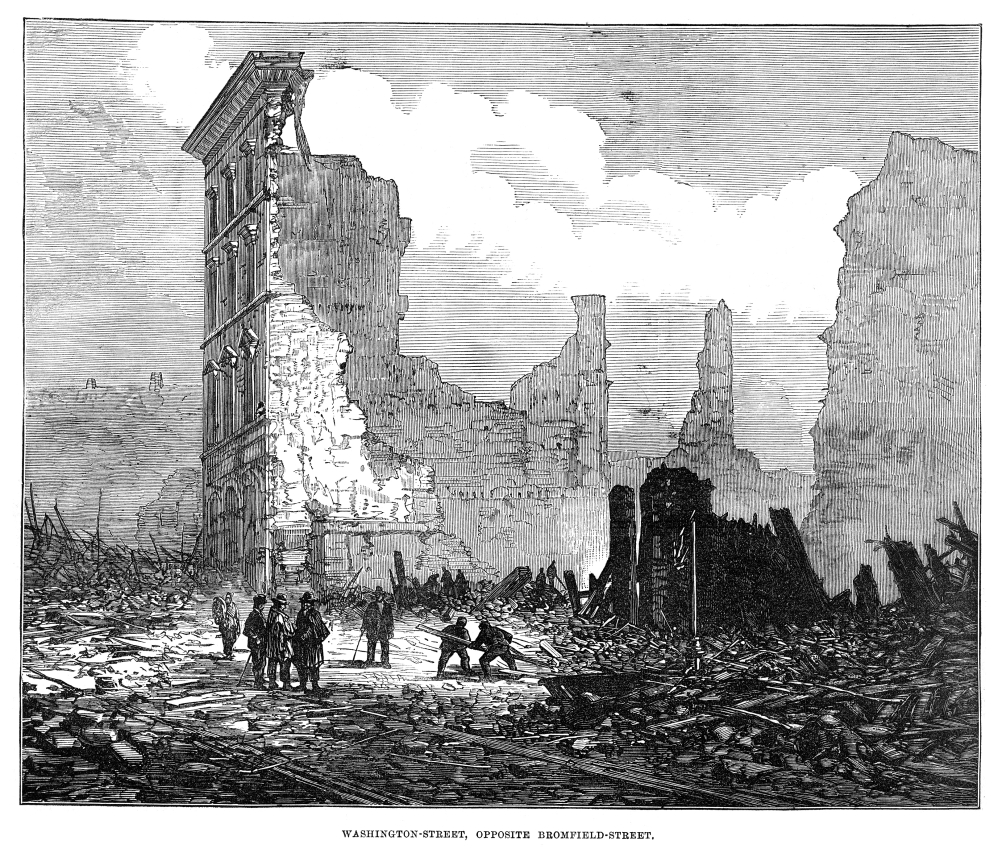

The street plan has been dramatically altered since the fire. Congress, Federal, Purchase and Hawley Streets for example have been significantly widened over the course of these past few months. Post Office Square was created at the intersection of Milk, Congress, Pearl and Water Streets. Atlantic Avenue has even been extended by dumping loose rubble into the adjacent harbor. Buildings are finally being made according to the construction codes, receiving upgrades and improvements in the process including their own fire alarms and fire hydrants. Rooftops are mostly made from ceramic or metal instead of wood at this point. Structures are also being kept within strict height limits. The firefighters have adopted a new type of mobile fire hydrant and the system of underground piping has been thoroughly improved as well. The locks have been removed from the fire alarms, meaning that residents have some recourse in the event that another blaze should break out. Within a couple of years, downtown Boston might just be back to normal.

The fact of the matter is that people have been putting up with devastating fires for centuries. While these were all highly destructive, most of them weren’t actually crippling. Fires often wind up having positive outcomes in the long run by providing an impetus for improved infrastructure and institutions. In much the same way as the terrible fire last year in Chicago, this could very well prove to be the case in Boston. I think the Great Fires of Rome and London make for pretty good historical precedents.

While nobody has been able to determine the exact cause, the Great Fire of Rome broke out on the evening of July 19, 64 AD in the densely packed shopping district near the chariot stadium where a variety of different combustible materials were being stored. The flames quickly spread to the surrounding apartment buildings. These were of course almost completely made from wood. The blaze continued for a total of nine days before firefighters were finally able to get things under control. Something like two thirds of the city had been reduced to rubble by then. While rumors to the effect that he ordered the fire to make way for a new palace ran rampant, there isn’t much evidence to suggest that Nero could have been behind the blaze. The emperor actually took several measures to prevent subsequent fires like widening streets and opening up the various forums. Nero also mandated that stone be used on the lower stories of most apartment buildings. Rome even got a bunch of new aqueducts, meaning that firefighters no longer had to rely on shovels of dirt and wet blankets to put out fires. The city was doing better than ever by the time that Nero lost his grip on power in the year 68 AD.

While the cause for the Great Fire of Rome has never been determined, the Great Fire of London can be traced back to a bakery. The blaze broke out shortly after midnight on September 2, 1666. The flames tore through the city for several days, burning something like 13,500 structures to the ground before a firebreak was finally created that stopped their spread. Rumors that foreigners were somehow involved quickly made the rounds, resulting in widespread violence throughout the city. London at the time had extremely narrow streets that were made even tighter by structures that extended so far outwards on their upper stories that buildings often met across back alleys. The city for the most part was made from wood and combustible materials including explosives were commonly stored in the basements of buildings along the Thames. London had basically no substantial means of fighting a fire. The result was of course disastrous, but within just over a decade, the city was almost fully repaired, receiving improvements and upgrades like wider streets and much more accessible wharves. The authorities even mandated the use of brick when it came to construction. Trying to avoid particularly big payouts, insurance companies also put together some of the first ever teams of professional firefighters.

Whenever they break out, fires like the one in Boston are often seen as ruinous, but the fact of the matter is that most of the time, cities are able to bounce right back. This was definitely true for places like Rome and London. I don’t see any reason to believe that Boston can’t be rebuilt. I’m sure that our city will be right back to its former self in a matter of years. Boston might even be a little bit better off in the long run.

I don’t mean to downplay the destruction. Boston just experienced a tragedy and the lives of its residents will never be the same again. I really do think on the other hand that we should take this disaster as an opportunity to improve the city. We’ve gotten a good head start when it comes to fire protection, but there’s plenty of room for improvement in other domains. The most important thing right now in my personal opinion is to improve living and working conditions in Boston by finding safe places for people to call their homes and closing down the sweat shops that have been filling our streets in recent years. We have certain moral obligations in this regard. The benefits of reconstruction shouldn’t just be focused on those who can afford to help themselves.

~~~

Justin Reeve is an archaeologist interested in pyramids, tombs and mummies, but he can frequently be found writing about parlor games, too. You can reach him by telegraph @JustinAndyReeve.