They Live is Evergreen

At the midpoint of 1988’s They Live is a legendary six-minute fight scene between the film’s protagonists, Nada and Frank, beating each other into the concrete of a Los Angeles alleyway. Aside from the sheer spectacle of it, it is a moment that best represents the message of director John Carpenter’s spry film: that the poor are pitted against each other so they may not face their true enemy of oligarchical America. Thirty years later, the movie still resonates as wealth disparity has soared, with 1% of the population hoarding 20% of the nation’s wealth.

They Live’s messaging isn’t just evergreen; it is the kind of film you can read from just the memes of star Roddy Piper putting on magical sunglasses and discovering subliminal messages behind advertisements. From within the crowded genre of science fiction dystopias, the film stands out. Instead of the flying cars of Blade Runner or the pop sensibilities of The Hunger Games, you get a blue-collar and largely grounded take on a crumbling society. It is a story about a homeless construction worker joining a resistance fight against alien invaders, who operate in plain sight, brainwashing the public through consumerism.

They Live imagines revolutionary heroes and condemns capitalism better than we typically see in dystopian films. There are lessons to be gleaned from this masterwork that spell out how we can make and demand better message films.

Mr. John Nobody

They Live’s protagonist John Nada, with a camping pack on his shoulder and a mullet on his head, is a far cry from the moody, philosophical, and slickly dressed dystopian heroes of the ’80s or today. Firstly, he is not connected to the film’s conflict through family; he hasn’t “lost someone” nor does he sacrifice himself for another. This bucks the genre expectation that the character needs to be connected to the world emotionally. The heroes of The Hunger Games and Interstellar can’t simply want a better world for themselves, there has to be a little girl on the line. But this ignores the material obstacles that make everyday life in the dark sci-fi future worth fighting to change. After all, since the enemy is flatly Capitalism, aren’t the indignities of living in the streets personal enough?

Committing to Nada’s lowly station, the film tosses the possibility of his being a “special” like the genetically destined revolutionaries of Star Wars or The Terminator. He is privileged with precious little information he doesn’t learn on his own and is granted aid by a group, the resistance. There is no mentor to commune with, no great plan that has a one in a million chance, but just might work. Nada can see no further ahead than his equally ordinary allies, like fellow construction worker Frank. Their first steps to revolution are instead shaking their internalized capitalism, reshaping their perspectives from the ground up.

When you think of dystopian heroes that trek across neon-drenched streets in a dogged effort to find justice, you often really are just thinking of law enforcement. These types seek to destroy, if not, reform the tools of oppression from within. The leads of Minority Report, Robocop, Dredd, and Equilibrium are propelled by morals that place them above the law while only taking tours of life under it. It’s a decidedly incrementalist expectation that these worlds need a cop to realize they are in fact the baddies and turn on their rulers.

Lastly, Carpenter shows us a step in a revolt that’s often treated as a given or relegated to montage: building solidarity. When Nada comes to Frank armed with the sunglasses and the fear, anger, and certainty radicalization has instilled in him, Frank refuses. Words turn to fisticuffs, becoming a moment which philosopher Slavoj Zizek argues represents the pain of stepping outside of ideology. Zizek says, “Ideology is our spontaneous relationship to our social world…We in a way enjoy our ideology.”

The fight’s brutality and Frank’s resistance signify the fear of facing one’s alienation, which can halt solidarity. But by stepping outside of our ideology we can see clearly; we are, in a sense, reborn. Nada forces the sunglasses onto Frank and shows him the world hidden under consumerism. His life plans are not mutually exclusive to his personal experience. He can never get ahead in a world operated by monsters.

A World Not Unlike Our Own

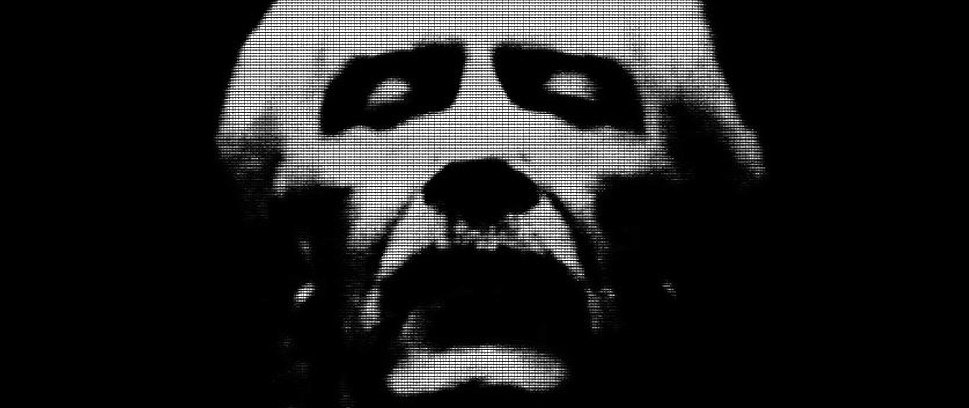

On the battle-scorched earth in dystopian films is an ever-present sense of weight. Authorities and their customs suffocate the populace, but They Live does this one better by depicting a society numb to its own suffering. During a ten-minute scene of near silence, Nada first tries on the sunglasses. They reveal a home computer billboard to simply, and famously say “OBEY”. A travel ad now reads, “MARRY AND REPRODUCE”. In a moment summing up his discovery, Nada looks into the camera while putting on the sunglasses to see a panoramic view of Downtown L.A. swamped in these hidden messages.

At this point in the movie, Nada has lost all his possessions and been separated from the few friends he’s made. He finds himself swimming in prescriptive messaging: “Buy this, feel good”. But none of what he sees in storefronts or newsstands can remedy his impoverishment. This scene is Carpenter saying, quite loudly, that of course, no one is selling what you really need, what would end your debts or feed and clothe you for life. Advertisers and consumer culture need you right where you are: unsatisfied at best, clinging to life at worst.

Early in the film, Nada finds food and shelter at a shanty-town run by volunteers who double as the resistance to the alien oppressors. The commune is likely modeled after Justiceville–a real-life, self-supported community started by activist Ted Hayes on Skid Row. And as in the film, Justiceville was condemned and bulldozed. In the film, it’s a long, monotonous scene of eviction, police brutality, and apathy.

It is notable that even the contemporary dystopia can not call out capitalism without also indulging in its pageantry. A significant part of the blockbuster franchise The Hunger Games is about courting sponsorship and creating a celebrity persona, should its heroine wish to survive a battle royale. The commentary is lost on no one: our hopes and even our very survival are contained to the individual’s ability to play the game. Your person is the commodity. Why this is set in the future and why the dehumanization of the heroine is meant to be exciting betrays any attempt to critique the class interests that made the rules. It’s only the future so we need not worry too much about the present, and the lethal reality show is there for our entertainment as much as it is for the fictional ruling class.

Time is a Flat Circle

It’s disappointing then that Carpenter offers up a mechanical solution at the film’s climax: bring down the cloaking device and reveal the aliens to the public. Truthfully the film could do without hidden aliens altogether. This simplification reminds me of a comment by George Carlin on Real Time with Bill Maher: “You don’t need a formal conspiracy when interests converge.”

They Live could have been bolder, but its timeliness also comes from its workmanlike approach. In a DVD interview, Carpenter once said, “The ’80s have never ended. They’re still with us today.” We don’t need to travel to a far-flung future to see class divisions. The future is now.