The Problem with ‘Sherlock’

In 1998, someone gave Roland Emmerich $130,000,000 to make a Godzilla movie. This was not because Emmerich was a fan of the storied Japanese Kaiju film franchise, but rather was down to the fact that he had earned a reputation for producing popcorn spectacles in less time and with smaller budgets than other directors.

The predictable result: a highly profitable blockbuster widely regarded by anyone with any knowledge of the source material as an utter disaster. Emmerich’s ‘roided out iguana was so visually and conceptually different from the beloved King of the Monsters that Kaiju fans even refused to grace the monster with its proper name, instead referring to it by acronym – GINO (Godzilla In Name Only).

Ten years later, Matt Reeves essentially remade Emmerich’s Godzilla with a found footage aesthetic and called it Cloverfield. No one complained. (Well, no one complained about it being a shit Godzilla movie, anyway – plenty of complaints about motion-induced nausea though).

———

There is a phenomenon in fan culture where said fans seek to preserve their favorite stories and characters in amber. This happens most often in the world of shared universe comic books, where so much is dependent on continuity and deep historical knowledge, but can occur wherever passion and storytelling intersect. If a writer takes a single narrative misstep, there are hordes of readers who will cry foul, citing endless sources from the printed canon like a lawyer at the trial of the century.

The best example of this is the case of Boba Fett, the bounty hunter introduced in Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. Until Attack of the Clones in 2002, Boba’s biography consisted of just three things:

The best example of this is the case of Boba Fett, the bounty hunter introduced in Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. Until Attack of the Clones in 2002, Boba’s biography consisted of just three things:

1. He had a reputation for disintegrating his quarry.

2. He cleverly tracked Han Solo when the smuggler went on the lam.

3. He met an ignominious end by being knocked into the Sarlacc Pit.

In Attack of the Clones, we meet Boba as a child and learn that his father, Jango, is also a fearsome bounty hunter, who was the template for the clone troopers. A Jedi beheads Jango, so Boba swears vengeance and…it really isn’t worth hashing it all out. The point is that the new backstory wasn’t nearly as interesting as the air of mystery that surrounded the character in the first trilogy. In fact, most of Boba’s mystique came from his armor and his silence – he only has four lines in the original movies.

Naturally, generations of Star Wars fans who secretly wanted to grow up to be silent, badass bounty hunters were upset. Some declared the character forever ruined, some chose to pretend the new movies never happened. Boba In Name Only.

——–

From the moment A Study in Scarlet saw publication in 1887, the popular imagination fell in love with Holmes. In the years since, the character attracted legions of fans, introduced deductive reasoning to the criminal sciences and was a defining character of the fledgling mystery genre. It is hard to think of another literary character that has had such widespread and enduring influence.

From the moment A Study in Scarlet saw publication in 1887, the popular imagination fell in love with Holmes. In the years since, the character attracted legions of fans, introduced deductive reasoning to the criminal sciences and was a defining character of the fledgling mystery genre. It is hard to think of another literary character that has had such widespread and enduring influence.

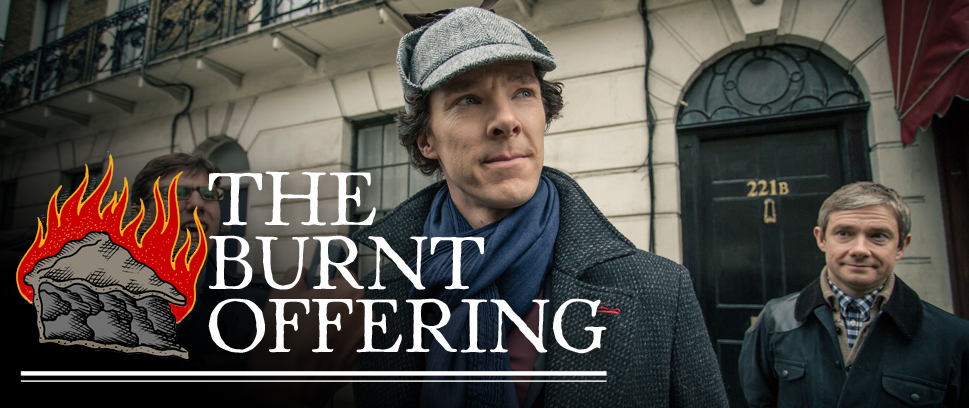

Beyond Arthur Conan Doyle’s original 56 stories, the mythology of the great detective has taken on a life of its own, spawning countless new installments and reinterpretations in books, movies, comics and videogames. Even now, 127 years later, in an age that couldn’t be more different from the impoverished streets of Victorian London, the figure of Sherlock Holmes resonates so greatly that we have no less than three modern reimaginings of the character (four, if you count Hugh Laurie’s House). Of these, the BBC’s Sherlock, starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman, is the worst.

Sherlock is Sherlock In Name Only.

——–

Thanks to the remoteness of his creation and his enduring longevity, Sherlock Holmes begs for reinterpretation and playful mash-ups. How would he fare against Jack the Ripper, or Dracula, or Cthulhu? What if Holmes was an actor and Watson was the great detective? What was he like as a child?

Thanks to the remoteness of his creation and his enduring longevity, Sherlock Holmes begs for reinterpretation and playful mash-ups. How would he fare against Jack the Ripper, or Dracula, or Cthulhu? What if Holmes was an actor and Watson was the great detective? What was he like as a child?

We can answer all these questions because we have a firm understanding of the character, thanks to Doyle’s original stories:

1. Sherlock Holmes is a bit of a dick with no patience for social nicety.

2. This is usually forgivable because of his staggering deductive powers and he is rarely, if ever, wrong.

3. Watson forgives it the most – the depth of their friendship is the real core of the stories.

So long as those three factors are present in some form, Holmes remains Holmes, even if he is a mouse, or a dog, a doctor, or in outer space.

At first, Sherlock seemed to be effortlessly adapting the character to modern London, a reflection of our times. The show’s use of on-screen text, montage and special effects to visualize Holmes’ deductions was a brilliant way to get the audience to play along with the mystery. Meanwhile, the chemistry between Cumberbatch and Freeman sold the difficult, but rewarding, friendship. And no one can dispute the love the showrunners, Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, have for the decades of Holmesian lore – the show is brimming with Easter eggs and clever references.

At first, Sherlock seemed to be effortlessly adapting the character to modern London, a reflection of our times. The show’s use of on-screen text, montage and special effects to visualize Holmes’ deductions was a brilliant way to get the audience to play along with the mystery. Meanwhile, the chemistry between Cumberbatch and Freeman sold the difficult, but rewarding, friendship. And no one can dispute the love the showrunners, Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, have for the decades of Holmesian lore – the show is brimming with Easter eggs and clever references.

Yet, in the most recent third season, it all went off the rails.

It started small, when Holmes quipped that an obsessive train enthusiast couldn’t possibly have a girlfriend. Yet he did. From there, he consistently misjudges people, mostly in the service of getting a laugh out of the audience. In Doyle’s stories, Holmes is only ever wrong once – “The Adventure of the Yellow Face” – and then only because the players in that case act out of compassion rather than criminality.

In the climax of the final episode, the nefarious newspaper magnate and blackmailer Charles Augustus Magnussen pulled the wool entirely over Holmes’ eyes. The detective is after Magnussen’s archives, which don’t exist – Magnussen has eidetic memory and stores all his dirt in a “mind palace” the same way Holmes does. When Magnussen reveals this, Holmes is flabbergasted.

Sherlock Holmes, the great detective, flabbergasted; I, a mere viewer, figured it out half way through. Unthinkable.

——–

The problem with Sherlock is that it uses all of the trappings of a great Sherlock Holmes adaptation, but forgets to include Holmes himself. Like Boba Fett and Godzilla, Holmes is being done a disservice, but it is hard to see because the show itself is so aesthetically pleasing. The character work is great (well, for the male characters – the women in the world of Sherlock are merely plot devices), the cinematography beautiful, the story structure elaborate and satisfying. It all but obscures the taint of laziness.

The problem with Sherlock is that it uses all of the trappings of a great Sherlock Holmes adaptation, but forgets to include Holmes himself. Like Boba Fett and Godzilla, Holmes is being done a disservice, but it is hard to see because the show itself is so aesthetically pleasing. The character work is great (well, for the male characters – the women in the world of Sherlock are merely plot devices), the cinematography beautiful, the story structure elaborate and satisfying. It all but obscures the taint of laziness.

The character Benedict Cumberbatch is portraying is interesting and dynamic, but his is not Sherlock Holmes. Rather than do the hard work of establishing a new character, Moffat and Gatiss are content to wrap Cumberbatch in a shoddy Holmes costume. They prop him up with 127 years of stories they couldn’t be bothered to write.

In Doyle’s stories, Mycroft Holmes has deductive powers that greatly exceed those of his younger brother. Yet Sherlock could be describing Sherlock when he says, “…he has no ambition and no energy. He will not even go out of his way to verify his own solutions, and would rather be considered wrong than take the trouble to prove himself right.”

Or perhaps Sherlock is the Holmes we deserve, an embodiment of our times: beautiful, engrossing, but ultimately counterfeit.

——–

Jeremy Brett is all the Sherlock Holmes Stu Horvath needs. Follow him on Twitter @StuHorvath.