Scenes from a Pinball Tournament in North York

I was in a church on a Saturday because of Roger Sharpe.

Before he came along, pinball was banned in New York City. It made sense. Pinball machines used to be for gambling. Launch the ball and you might get something depending on where it landed. Usually, though, you didn’t. At least it was more fun than a slot machine. In the early ’40s, Fiorello La Guardia, the then-mayor of New York City, went on a crusade, putting a full push into destroying the machines and dumping them in the river. Even after the payouts stopped and flippers were added, several states were still weary of them. They became a shorthand for illicit smoke-filled backrooms, for latchkey kids and drop outs.

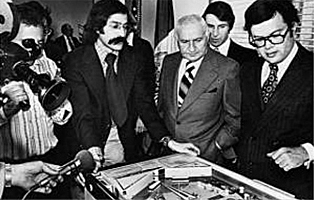

By the ’70s, the pinball industry tried fighting back. They needed to prove that pinball was no longer a game of chance, but a game of skill. The industry ended up getting a meeting with New York City councilors to try to get the ban lifted. Here’s where we get to Roger Sharpe. He was the star witness on the pinball side. He was going to prove that pinball wasn’t a game of chance. They set up a machine and, in front of the councilors, he pointed to a spot on the board and called the shot. When he made it, nobody was more surprised than Sharpe. New York City lifted its ban, and slowly thereafter, so did the most of the country. Pinball was back.

By the ’70s, the pinball industry tried fighting back. They needed to prove that pinball was no longer a game of chance, but a game of skill. The industry ended up getting a meeting with New York City councilors to try to get the ban lifted. Here’s where we get to Roger Sharpe. He was the star witness on the pinball side. He was going to prove that pinball wasn’t a game of chance. They set up a machine and, in front of the councilors, he pointed to a spot on the board and called the shot. When he made it, nobody was more surprised than Sharpe. New York City lifted its ban, and slowly thereafter, so did the most of the country. Pinball was back.

If Sharpe hadn’t made that shot, who knows if I’d be in a pinball tournament in a church in northeastern Toronto? Who knows if pinball machines would really even still exist?

———

I forgot to enter the Canadian Pinball Championships. Well, not really – I thought it was a one-day deal, but it actually started on the Friday. By the time I arrived, there was already a room of, mostly, men with a one-day head start. Unprofessional, no excuses, etc.

My friend Kotzer and I made our way inside into the church’s cafetorium. It was smaller than I expected. The entire tournament fit in a room made for anti-smoking Sunday school presentations. A Toronto Maple Leafs clock that you’ve seen a million times in rooms just like this was ticking away. There was a non-regulation-height basketball net still up on the wall. Hugging every wall were pinball machines and in front of each of them were bodies locked in intense concentration. Clanking, clunking and endless bump/bump/bumps – one game had a loud siren on top of it blaring – under banks of white-hot fluorescents. This room was not made for sinners with hangovers.

Kotzer was there to do a legit story, and I tagged along because I didn’t know a single thing about pinball. Kotzer’s got a big beard that wavers between disheveled and unkempt, and though he’s not a fast talker, I sometimes feel like he’s talking to me from three minutes in the future. It’s just the way the significance of things he says slowly come into focus. He eyed the machines in the way every other competitor did: There was a warm smile, but quick, hard eyes trying to unlock the alchemy behind a high score. He is an actual wizard, I think, and pinball is just one of the dark arts he practices.

Mike was Kotzer’s contact. He was a tall, older dude, and he gave us the grand tour of the Canadian Pinball Championship. He did this thing where he’d stop after a sentence and his eyes would flit around, looking for trouble. It’s the kind of look you see on unpracticed adulterers and sleep deprived event planners. He was tired, but gracious and helpful, answering each of Kotzer’s questions. The tournament was run by the Toronto Pinball League (TOPL). Mike helped organize and set up the competition along with a few other volunteers. “Volunteer doesn’t pay well,” he said with a smile. All the money collected from registration went into prizes, and the silent auction and raffle – for bundles of Star Wars action figures, pieces of a Wizard of Oz game being made by a new pinball manufacturer, framed sci-fi posters – were going to be donated to Sick Kids Hospital. The machines all came from members of TOPL, most of who were competing. Even Mike tried getting in on it, when time allowed.

We decided to have a look around for ourselves. There were about 60 people in the tournaments. A few were from out of town. Pittsburgh and Buffalo, mainly. Now, Pittsburgh, that’s a pinball town. It’s the home of the Professional and Amateur Pinball Association, and it hosts the world championships, which completely dwarfs this already small-time affair. Nobody here seems to really be bothered by that. Eyes are locked on balls and scores.

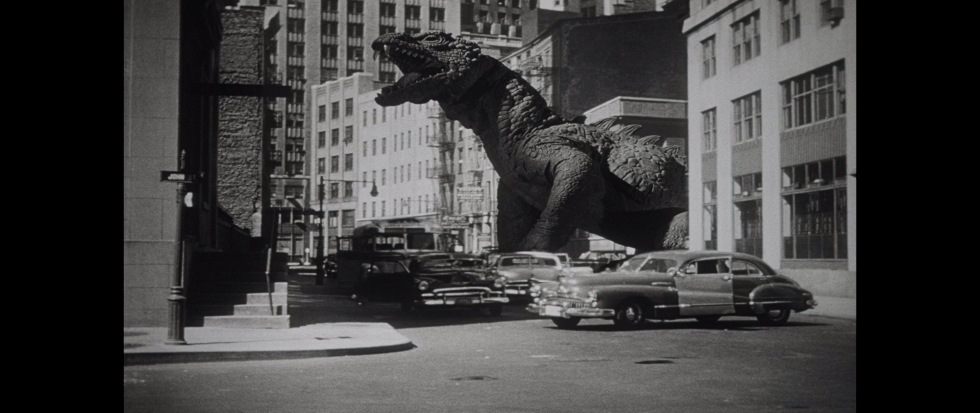

Kotzer said to me, “You really get a sense of what movies they thought were going to be big.” The Shadow, Congo, Godzilla (poor Matthew Broderick). An orange LED display flashed “Say No to Drugs” on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a game based on a movie celebrating a creature who seduces woman and drains them of their blood. People sat in chairs and waited their turn to get another go at the machines. Volunteers milled around and recorded scores and took them to the overseers of the tournament watching from a short stage. Alec Baldwin’s face on the Shadow machine looked more like Tim Curry than the goggled version on the backglass of the Congo machine. A man with a bandana wrapped around his head flipped the double bird in his smug face. Nobody waited behind him.

Mike found us again while we watched a game of Pin*Bot. “Can I ask you a favor?” He wants us to not use his last name. “I have a very ununderstanding boss.” It is almost impossible to not indulge Mike in his request.

———

A dozen pinball machines is a cacophony, but a single old machine is a songbird.

It is the playoffs for the classics division. The herd has thinned. Groups of three face off against each other. The highest-ranked player from the qualifiers in the group chooses the machine. There was no animosity here: When the spell broke and the players stepped away from their games, they mingled and chatted about their collections. One guy showed off a database of table-specific tips and tricks to another player on his tablet. All the while, the plunks of the Volley machine rang out through the room.

TX-Sector attracted some attention. It spent most of the day disassembled and folded in on itself in a corner of the room. Everybody huddled around when they took off the bindings and drilled the legs in. The backglass looked like a rejected Journey album cover, a trippy acid-washed futurescape that was outdated before it was even released. The only thing that aged well was the music, some decent electronic jams on a day filled with digitalized voices and unrelenting noise. When it was set up, the people standing around the machine each took a minute to “test” it out, while the rest of the huddle marveled.

It was time to get serious. The crowd, begrudgingly, dispersed and went to their own match-ups. I stayed at TX-Sector. The three competitors played three balls, alternating turns. One of the competitors was calm, exercising an extreme economy of movement. He only used the flippers when he had to. He was quiet, careful. All of this cool fell apart when he was in trouble. His body contorted, he hopped on one leg, he bit his tongue. He loses it, then he loses.

One of his challengers was his complete opposite. He was a bit older, a bit taller, a bit wider. He kept jamming on the buttons even when the ball was nowhere near the flippers, a fidget that got annoying pretty quick. For emphasis, he smacked the buttons with the palm of his hands.

They danced for a few rounds, but it was easy to see that Immovable Object had the Unstoppable Force beat. When his score was enough to secure first place, he let the ball drop. Kotzer asked why. It’s pinball etiquette. When your win is secure, there’s no need to show off.

———

We decided to leave. The playoffs were going to be a long, drawn-out affair, and Kotzer heard whispers that it could even go on to midnight, something neither of us really needed to see. We said goodbye to Mike. Kotzer flashed some photos, and he wanted to get a few of the machines in the kids’ tournament.

The adults had their pick of a casual division, a pro division, or the classic division, but the kids got to have fun. The World Cup ’94 machine had two boxes set up on the floor, one to the left and one to the right, each with a soccer ball in them. To activate the flippers, you had to kick the ball. You lose precision, and the ability to set up the ball. It’s sacrificing the intense score climb for a looser game. In that same spirit, The Avengers machine was played while wearing giant Hulk fists. What you lose in subtlety, you make up in goofy joy.

One of the games tucked in the corner was MLB Slugfest, a game I’d never seen before. It was smaller than the other pinball machines. The board looked like a baseball field with a single flipper at the bottom and targets in the outfield. There were buttons for the pitcher. Curve ball, fast ball, that sort of thing. There was a button to swing the bat, a button to steal bases. I popped two quarters in and I went at bat.

Kotzer chose pitches and, with no real strategy on my end aside from making cocky boasts, I swung the flipper, watching blurs of light run the bases if I hit the right targets. Then the game took a turn for the worse when we discovered how to steal bases. Every few seconds, with gleeful mischief, one of us would repeatedly jam on the “Steal Base” button, prompting the other to jam the “Throw Out” button and try not to curse loudly in a church with kids around when we were caught out. I could’ve stayed at that machine all day.

———

When Roger Sharpe made that shot, he changed the fate of pinball. He rescued it from being a weird footnote of early 20th-century history. Thanks to him, it thrived, and now it’ll be a weird footnote of late 20th century history.

I went into this thinking that this was a hobby buoyed by the passions of a frantic few, those who are willing to play until midnight, those who are willing to drive from Pittsburgh to play while their girlfriends enjoyed the beach, those who will take a sick day and risk being fired to organize the thing. I also thought that the true legacy of Sharpe’s shot, of his precision, was the change in how we thought of pinball. Pinball went from being an idle amusement – and why should that ever be considered dangerous? – to something more straightforward, something one can master and attempt to conquer. It became a sport.

I went into this thinking that this was a hobby buoyed by the passions of a frantic few, those who are willing to play until midnight, those who are willing to drive from Pittsburgh to play while their girlfriends enjoyed the beach, those who will take a sick day and risk being fired to organize the thing. I also thought that the true legacy of Sharpe’s shot, of his precision, was the change in how we thought of pinball. Pinball went from being an idle amusement – and why should that ever be considered dangerous? – to something more straightforward, something one can master and attempt to conquer. It became a sport.

But watching the tournament, the kids in this room and the adults in the other, the score mattered and it didn’t. The competition, the prize money, the cafetorium, the overcooked hamburgers, the out-of-the-way location, the ever-climbing scores, none of that really mattered as much as getting a chance to play pinball for a few hours. I looked at this like it was a competition, but it wasn’t. Not really. There were definitely no losers here today: Everybody got what they wanted.

There were no kids left now. The machines were off, quiet, no tempting lights and high score come-ons. Another dude wandered into the room. He looked at the World Cup ’94 table and tilted his head, eyeing it up.

The man ducked down beneath the machine and flipped a switch. It came to life. The colors lit up, bolder, the machine hum kicking up like a white noise we didn’t know was missing. He positioned himself in front of the machine, unsure of his stance, and pulled back the plunger. He readied his foot to kick the ball and softly tapped it when the ball was near the flipper. It was a bit awkward, but he was having a good time.