The American Culture of Horror: Three Things

Part 3: Watch the Skies

Formlessness was one of H.P. Lovecraft’s favorite notions. His tendency to describe the creatures in his stories as indescribable has become something of a running joke in the horror genre, but at its heart is something sinister.

If something truly lacks a shape, I cannot understand it. If it has no borders for my eye to trace, I cannot comprehend it or, if those borders are constantly changing, I can do little more than spend my mental energy constantly attempting to comprehend it. Something like that would be visible and invisible all at once and my mind would quickly exhaust itself trying to reconcile that fact with the more comfortable physics of the world. In fact, since sensory perception is largely an involuntary function, my brain would be attempting to comprehend without my active participation. The gears of my intellect would be stripped alarmingly fast.

But forget trying to understand the formless, hungry blackness that wishes me harm. Let us instead ponder what existence without a shape would consist of. No form means no real physical identity, no sense of self. Constant changing of shape would also mean that the physical interface with the world would constantly be changing in turn. Basic understanding of the material world would be blunted. The struggle for comprehension would be titanic, leaving only utter madness and hungry instinct.

Because everything needs to eat.

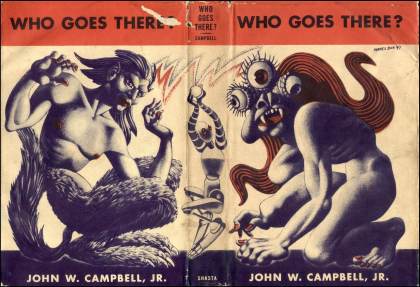

In 1938, two years after Lovecraft’s death, one of the most terrifying creations of the 20th Century was born in the pages of a story called Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell. Formlessness, isolation and loss of identity are central to the tale.

In 1938, two years after Lovecraft’s death, one of the most terrifying creations of the 20th Century was born in the pages of a story called Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell. Formlessness, isolation and loss of identity are central to the tale.

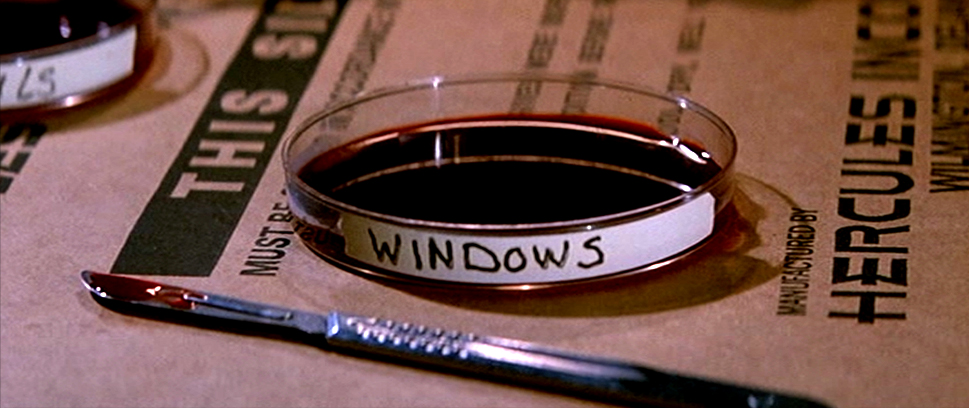

A group of scientists at a research base in Antarctica discover a crashed spaceship in frozen in the ice. They recover an alien body, presumably the pilot, and thaw it out for study – but the creature was only hibernating. It wakes up hungry, immediately devouring a scientist and a sled dog. This reveals its insidious power: the Thing can take on the shape, memory and personality of anything it eats. Each victim also increases the Thing’s mass, which eventually splits into independent creatures in a form of asexual reproduction.

The ensuing murders infect the team with a tense paranoia. As they learn more about the Thing and attempt to flush the duplicates out of their ranks, the situation becomes more and more desperate. The story reaches a fever pitch once the researchers realize that they are not only fighting for their own survival, but for that of the entire human race – should the Thing escape the Antarctic, it would run rampant through the Earth’s population.

Who Goes There? is the stuff of pulp legend and has since been made into two films, The Thing from Another World (1951) and John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), both of which are classics in their own right (though the plant creature of the 1951 film is more the realm of sci-fi and outside the scope of this article).

Who Goes There? is the stuff of pulp legend and has since been made into two films, The Thing from Another World (1951) and John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), both of which are classics in their own right (though the plant creature of the 1951 film is more the realm of sci-fi and outside the scope of this article).

Carpenter’s film is a masterwork of suspicion, murder and desolate atmosphere. Like many of his best movies, his use of isolation forces his characters into desperate but believable situations until the sense of doom becomes almost palpable. As the Thing works its way through the team, it is dizzying, as a viewer, to try and reason out which characters have been taken over by the creature. Be they communists or terrorists or hungry aliens, The Thing preys upon the chilling idea that the people around us can always be more than we expect.

There is no hope in The Thing. Antarctica is almost the farthest a human being can be from other human beings. If the scientists could call for help, its arrival would almost certainly give the Thing passage to the larger world, which would spell the end of mankind. Even when the creature is dispatched by blowing up the entire station, it leaves the survivors to face an inevitable death from exposure.

The various bleak iterations of Who Goes There? have gone on to influence countless films, comics, and books that have come after them. The overriding message was to watch the skies with wary eyes, for we have no idea what is really out there.

It is a lesson learned well, now that mankind sails above the skies.

Continue to Part 4: Dead Space

~

Tune in tomorrow for the final part of The American Culture of Horror, when I take a look at the Dead Space videogame franchise. In the meantime, you can watch me change shape on my Twitter @StuHorvath.