How Music Makes Tchia’s Story Hit Home

A number of patterns have emerged in the design of open world video games. It’s hard to imagine one that doesn’t contain quest-based stories or some kind of collectible that rewards exploration. In-game maps have become so common that the decision not to include one (e.g., Subnautica, A Short Hike, or The Pathless) has become a statement in and of itself. One overlooked aspect is the implementation of overworld music. Composers have tended to focus on supplying each village and biome with a distinct soundscape. While this approach is not without benefits, Awaceb’s Tchia, published by Kepler Interactive in 2023, demonstrates what can be gained by also scoring the player’s progress through the game.

As an open-world game, Tchia stands out for a lot of reasons. For one, it was inspired by the developers’ familial and cultural connections to New Caledonia. The titular character and avatar is a 12-year-old Kanak girl on a quest to rescue her father. Despite the challenges of scoring an open-world game – and a limited-budget open-world game at that – it’s surprising to hear John Robert Matz’s background music do something fairly novel: express character development.

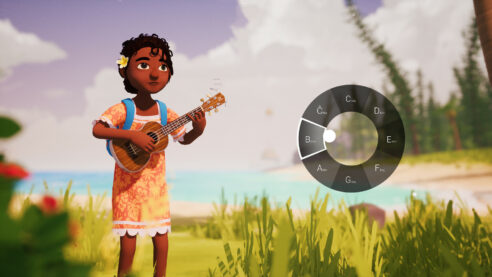

One of the clearest illustrations of this is in the music that accompanies Tchia’s interactions with Louise, a French settler who lives in the town of Weliwele. Shortly after they first meet, Louise sings “Cocotte, la petite perruche verte” while the player performs Tchia’s ukulele accompaniment as a rhythm game. Later in the story, Tchia returns to Weliwele to verify Louise’s safety. Almost as if they were in a musical, they perform the song again, but this time Louise sings it in Drehu, Tchia’s native language. Matz could have merely replaced Ella Vidin’s vocal track but instead composed a new accompaniment for the reprise. Whereas Western symphonic strings and bamboo flute accompany the French version, the latter half of the Drehu reprise features Indigenous instruments and rhythms Tchia previously performed in the Pilou ceremony in the Kanak village of Hunahmi. (If you’re interested in hearing more about the New Caledonian influences on the score, check out Matz’s talk at GDC 2024.) The changes in the reprise hint at what Louise was doing while Tchia was confronting Meavora – learning about Tchia’s language and culture – and this lends support to their budding romance. At the conclusion of “Cocotte sine neköi piny,” Tchia and Louise share their first kiss and Louise transfers the flower from Tchia’s left ear to her right, signaling that she is no longer single.

In true melodramatic fashion, immediately after the girls discover their feelings for one another, Meavora’s henchman descends on Weliwele, capturing Louise and several of Tchia’s other friends. After this point in the story, something small but significant happens: the music in the towns they lived in changes. Appropriate to Weliwele’s focus on farming and ranching, the pre-kidnapping music in this area draws on several aspects of the pastoral musical style. Think of the pastoral as the cottagecore of music. It has been the soundtrack to narratives of returning to the land from Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony to Concerned Ape’s Stardew Valley. Features that unite these disparate examples include simple melodies in the major mode, straightforward harmonies, rocking accompaniments, and the use of wind instruments such as the flute, but all the player has to know is the feeling of “Ah, this music sounds like simpler times.”

The pastoral style isn’t as much about nature as it is about harmonious relationships between humans and nature. Without its people, Weliwele feels… off, and the post-kidnapping music reflects this. Matz scored “Lonesome Weliwele” for guitar alone, at a much slower tempo, and with some unexpected harmonies. Both Weliwele tracks are in the major mode, but the pre-kidnapping music is unambiguously major, whereas the post-kidnapping music contains notes and chords that are borrowed from the parallel minor, making it sound more sombre while also losing its pastoral feel. This musical change not only underscores Tchia’s sadness at finding Louise’s home empty but also suggests how the player ought to respond to this story beat.

This moment in Tchia illustrates one of the issues with static location music: most open-world games have stories and characters who develop and change. These changes are communicated through the characters’ choices or new abilities they acquire, but often not in the visual or sonic appearance of locations, even story-significant ones.

Matz’s decision to write multiple cues for Weliwele and several other towns made his task longer and more complicated but paid off in terms of the ways his score supports the game’s story. To put this into perspective, even AAA open-world games such as The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild do not have location music that responds to story events. Many of Breath of the Wild’s towns and regions are on a day-night cycle, which contributes to the atmosphere and sense of the passage of time, but does little to support either the story the developers are telling or emergent narratives of the player’s creation. Matz’s decision to focus instead on story-related adaptivity was a smart choice because of the importance of the characters and story to Tchia and its players.

Tchia is by no means unique. There are other games that that score players’ large-scale progress, not merely their moment-to-moment actions. For instance, after each boss battle in The Pathless, Austin Wintory’s score completely changes and the previous exploration music is never heard again. Another notable example is Chicory: A Colorful Tale, for which Lena Raine composed four different tracks for the town of Luncheon, which reflect the avatar’s growing self-doubt.

For players to feel that the music is scoring their progress, they first need to recognize that the music changes. Matz’s tuneful and memorable compositions make this easier than the current tendency towards more ambient music in games. Players also need to know why the music changes. In Tchia, it’s obvious why “Lonesome Weliwele” is a downer. It’s moments like these that show what story-driven game music can do. The story knows, the music knows, and so the player knows. It makes each change matter, it makes each piece of music matter, and it makes Tchia’s story hit home.

———

Nina Penner is Assistant Professor of Music at Brock University. She is currently writing about the roles music plays in open-world games.

Paul Drotos is a bizarre creature and Masters student of Game Design at Brock University. Their work focuses on the implications of design choices in video games.