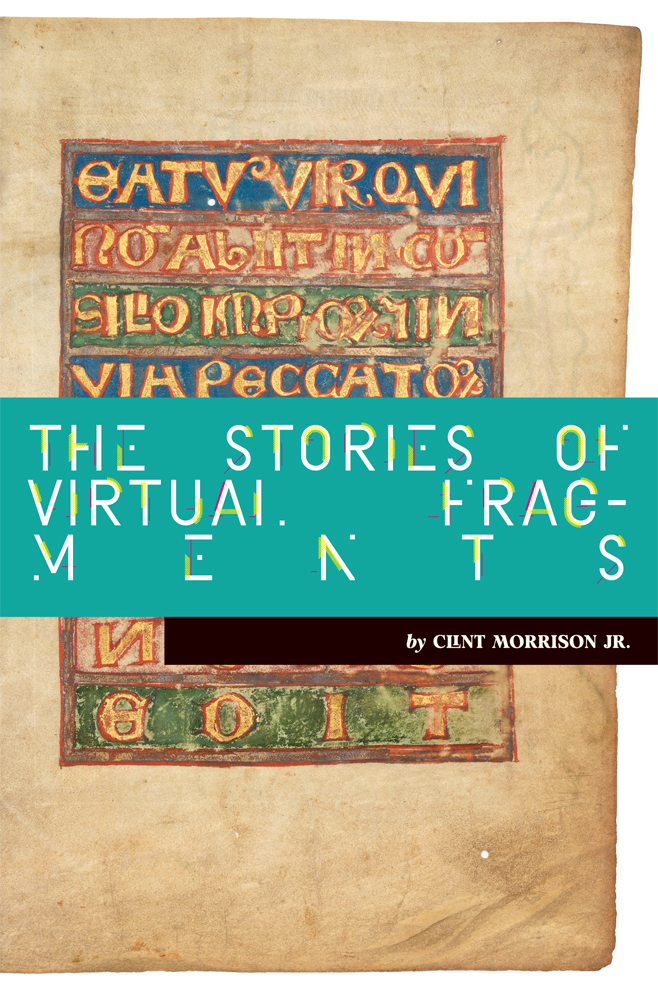

The Stories of Virtual Fragments

This is a feature excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly #169. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

I stumbled upon a single-sided document during a recent replay of Remedy’s Control’s AWE DLC. The document belongs to the files of ID AWE-10. Its more complete title is “Bright Falls (1976) Supplement.” Finding documents like this one, lightly redacted, is not uncommon in Control – they litter the Oldest House – but the content of this one fragment gave me pause.

ID AWE-10 narrates the events of a flood in Bright Falls during a rehearsal of a rock band, the Old Gods of Asgard. When the narrative finds the band, the document reads:

“Tor Anderson had been struck by lightning and Odin Anderson had cut out his own right eye (a possible ref. to Norse deities [REDACTED] and [REDACTED]?)”

The redaction of the references does little here. The Andersons share their names with Norse deities whose names may be redacted but are pretty clearly Tor (or Thor) and Odin. The brief narrative intersects with familiar characters and moments from Remedy’s Alan Wake, where players find the now former rockers undergoing treatment at the Cauldron Lake Lodge.

The document creates connective tissue in the Remedy Connected Universe. The classified, redacted, imperfect single page belongs to a collated group of documents. Theoretically, these pages were once potentially bound or filed together.

Player choice and time limitations mean there are never any guarantees that players will find the unbound documents within the game. Within a save file, they may remain apart, separated. Similarly, players are never guaranteed that these fragmented pages will ever lead to a complete story even if they collect them all.

Control, like Remedy’s Alan Wake and Quantum Break before it, tells some of its most interesting stories through these fragments of digital ephemera. Of course, Remedy isn’t the only studio to include such documents as collectibles. Most modern games often present players with three forms of narrative: the main story, the side quests and these collectible, fragmentary documents. They present the latter form of narrative as a series of (non-linear) stories and – except for when they become intertwined with the main or significant side quests – often as wholly optional content. These collectibles sit awaiting completionists, trophy and achievement hunters or the curious to find them.

These fragments coalesce into digital ephemera, left obscure or abstract in incomplete collections. Here, I consider these pieces of digital ephemera in relation to the living collections of physical fragments, specifically medieval fragment collections.

The study of medieval manuscript fragments is called fragmentology. Fragments, like collectibles found in videogames, come in all different shapes, sizes and conditions. They also have had varying purposes or are the result of different historical events. A manuscript fragment is the potential result of multiple realities. For instance, a medieval manuscript may have been taken apart during the Middle Ages or Early Modernity for its pages to serve pragmatic uses from binding support to book covers. They may also be the product of manuscript breaking, where a modern collector has broken a codex like a medieval bible or liturgical manuscript to sell off one page at a time. Once broken, it is difficult to recollect and reassemble the once-whole book.

In videogames, the breaking of narratives into fragmented ephemera serves a mostly pragmatic purpose. They act as worldbuilding tools to flesh out the histories and lore of our favorite digital pastime. Fragmentology usefully provides a lens to approach these documents within games. Like fragments once belonging to larger manuscripts, digital fragments sit in the corners of narratively driven worlds, such as those belonging to the Remedy Connected Universe, Arkane’s oeuvre, Guerrilla Games’s Horizon series and even in Naughty Dog’s more linear The Last of Us. They are intentionally broken texts.

They aren’t always as bureaucratic as ID AWE-10. Article #27 in The Last of Us enjoys a little more fame than most videogame fragments. Not because it is a beautiful illumination or postcard – in fact, it becomes a missable collectible further crumbled and thrown aside. Article #27 is the infamous handwritten letter from Frank to Bill that outlines the end of their relationship from Frank’s perspective. The letter is but one clue of Bill and Frank’s relationship, ending it in a heart-wrenching couple of paragraphs.

Article #27 was popular enough to become tied to the trophy “In Memorium” in the Playstation 5 Remake The Last of Us: Part I. More significantly, the story contained in the fragment spawned Frank and Bill’s own episode “Long, Long Time” in the HBO show. The writers and showrunners of the show revise their love story, ending with a very different note with a different readership as it ultimately depicts a different trajectory for Frank and Bill’s love story. Article #27 becomes a variant story, kept only in part.

———

Clint Morrison Jr. is a medievalist and gamer currently writing from Austin, TX. You can find him at clintmorrisonjr.com and on BlueSky.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 169.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!