A Tale of Two Relics

The idol is cursed. This much is evident from the first scene in Color Gray’s 2022 game, The Case of the Golden Idol, which sees one character murdered by another for possession of the idol. The idol’s story is one of power, violence and greed, and it’s up to players to untangle the bloody threads that spell the relic’s history, using a Mad Libs-esque mechanic not dissimilar to Lucas Pope’s 2018 game Return of the Obra Dinn. They share a number of similarities, but each stands on its own as an engaging and innovative entrant into the mystery genre thanks to their unique take on logic-based puzzles.

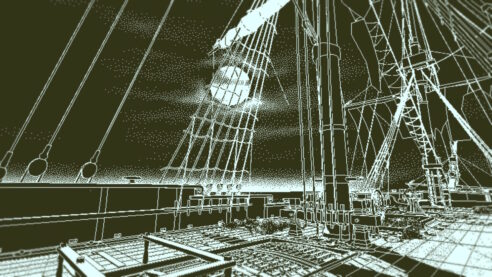

Both games ask the player to correctly identify a victim and a cause of death, at least at first. Return of the Obra Dinn asks the player to discover the fate of each passenger and crew member aboard the Obra Dinn after it disappeared five years prior to the game’s start, at which point it reappears, empty. In The Case of the Golden Idol players determine the fates of the wealthy Cloudsley family over the forty years during which they possess a rare artifact. Obra Dinn‘s true timeline reveals dark and surprising secrets, while the scenarios and chain of events in The Case of the Golden Idol become increasingly elaborate as the story progresses. Both games are also concerned with the fate of two relics – a magical shell aboard the Obra Dinn draws all manner of trouble to the ship, where The Case of the Golden Idol‘s titular golden idol visits violence upon those who hold it and those who seek its power.

But perhaps the most interesting thing in the comparison of these two games is not in their similarities, but in where they differ. The main character in Obra Dinn is an unnamed insurance adjuster who uses a magical pocket watch that rewinds time, allowing them to walk amongst carnage and calamity to observe scenes of death from all angles. The player then uses these observations to fill out the log book that chronicles the disastrous final days of the Obra Dinn’s voyage. In The Case of the Golden Idol, there is no such proxy for the player. Instead, players click through two-dimensional tableaus, examining people and artifacts for clues. In “thinking” mode, the player then uses the clues to complete scrolls, identify portraits and analyze various aspects of the scene. Eventually, this paints a complete portrait of the ruin the idol—or more accurately, reckless pursuit of the idol’s power—wrought over the 40 or so years it was in the possession of the wealthy Cloudsley family.

Return of the Obra Dinn and The Case of the Golden Idol offer unique powers of observance. Beyond that, they also offer unique perspective. At the conclusion of Return of the Obra Dinn, the actions of the passengers and crew are categorized and tallied. Dishonorable actions like murder, theft and abandonment result in a fine or forfeit of estate; exceptional performance and valor results in a small payout for the person’s surviving family. This is a sobering reminder of the East India Company’s power and influence at the time. The agent serves a specific purpose, which is to investigate and reclaim the company’s property. However indirectly, the player is complicit in protecting the East India Company’s interests, which for hundreds of years included colonialism, slavery and monopolizing trade. The insurance agent anchors the player to a specific moment in time, to a specific political alignment.

Return of the Obra Dinn is a nonlinear story; the first deaths discovered were the last to occur, and the mystery of the story is in piecing together the series of events that preceded the ship’s disappearance and return.

The Case of the Golden Idol, on the other hand, is entirely linear. As the plot progresses and Edmund Cloudsley and his associates use the idol to gain popularity and influence, the tension of the game hinges on whether anyone will be able to prevent them from rising to power and usurping the English monarchy. The answer is yes, thanks in large part to Edmund’s hubris. In the end, neither the idol nor his wealth can save him and the rebellion is destroyed along with the idol. To observe Edmund’s downfall provides a catharsis different from Return of the Obra Dinn‘s satisfaction of a job done. The record of events in The Case of the Golden Idol serve as something of cautionary tale rather than a ledger of balances paid and owed.

Because the two games share such similarities, the question of who stands behind the camera of The Case of the Golden Idol is an interesting one. As a two-dimensional point-and-click game in which players are interacting with largely static environments, the player doesn’t need a proxy; they already have total freedom to explore the scene. The lack of player character acting as an intermediary between the player and characters in the game creates distance, and the omniscience granted as a result of both the distance and the player’s freedom of movement lends the narrative a level of objectivity.

Where the insurance agent’s presence in Return of the Obra Dinn adds an additional layer of story to scrutinize, the lack of presence in The Case of the Golden Idol makes the player’s level of knowledge feel more voyeuristic and creates a different sort of tension in the narrative. Unlike the insurance agent, players have no material stake in the Cloudsley family’s actions, yet know the intimate details of their ambitions. The captivating drama combined with smart deductive logic puzzles feels like watching an incredible piece of theater that self-awarely acknowledges a shared relationship with the audience. The show is made all the more engaging by the participation of both parties.

The comparisons between The Case of the Golden Idol and Return of the Obra Dinn have merit, but the places where they differ are what make them such unique standouts from the mystery genre.

———

Madison Butler is a writer and self-proclaimed jock. She is an editor at Sidequest (sidequest.zone), co-founded the blog Critsumption and once got really into powerlifting via Fitness Boxing for the Nintendo Switch. Find her on Twitter here.