Surviving Humanity

This is an excerpt from a feature story from Unwinnable Monthly #157. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

To some, the end of humanity may not be a tragedy, more a curiosity. That’s certainly the case for a lone cat in Blue Twelve Studio’s action-adventure Stray, after she plummets into the ruins of civilization. For others, tragedy comes not from the demise of humankind itself, but in the ripple effect of its death throes. Take the fox in Herobeat Studio’s survival game Endling: Extinction Is Forever, for instance, trying to nurture her cubs in an environment dissolving under the weight of human failure.

These two games, released on the same day in July this year, form a two-pronged critique of human hubris. Cat and fox provide low-slung perspectives from which we observe the collapse of the Anthropocene and what rises in its place. Their representations of humanity’s (self-)destruction are like many we’ve seen before – Endling’s opening could almost be a dark alternate climax for Disney’s Bambi, as fire envelops the woodland and a panicked stag succumbs to the smoke – and follow a branch of modern apocalyptic fiction, such as Don’t Look Up, that feels increasingly fatalistic. They are indictments of a (neoliberal capitalist) civilization, laying out straight our collective idiocy, apparently concluding that all there is left to do is hope something better takes our place.

But when placed side-by-side, as befits the publishing schedule that saw these titles born as twins, they reinforce one another’s underlying currents. Approaching the apocalypse from either end – before and after – their themes cohere into a stronger whole that might prompt us not to forsake humanity but rethink it as something radically creative and outward-looking.

* * *

After the forest fire in Endling, which our fox narrowly escapes, humanity’s presence and destructiveness only increases. The pregnant vixen finds shelter inside a small rocky hollow and pushes out her cubs. Now you’ve got to venture outside to gather food, respecting her nocturnal rhythm to return before sunrise. The people nearby move during the day, of course, so when you emerge each evening, you note how they’ve eaten further into nature – excavating, building, dumping and polluting.

The fox lives among the side effects of human industry, a concept explored by the game’s 2.5D mode of exploration. What looks like an open world is really a network of linear paths, intersecting at junctions. These single lane roads signal how your attempts to hunt and forage are throttled by the dominant species, complicated further by parked vehicles, piles of refuse, guard dogs and locked gates that force you to find alternate ways around. Rather than puzzles to overcome, such obstructions simply disappear at intervals, linking your access to the world to human activity. All the while, natural sources of food diminish, forcing you closer to the enemy.

When the seasons change, you lead the cubs away and establish a new den in the shell of a discarded machine. As you move, in the background, the plight of humanity begins to unravel. We see intensive farming operations, intensive logging, then a kind of environmental refugee camp, with caravans and shacks housing the displaced. Finally, it all washes away, leaving only a desert where forlorn survivors trudge hopelessly, hunting for scraps like the fox herself.

There’s minor hope in the ending, as the cubs have by now learned survival skills of their own. But it feels like hope for a post-human world, while people themselves have learned nothing. Endling is an angry critique of our short-sightedness. Human endeavor here is disorganized and desperate, consuming nature in a way that undercuts its own ability to thrive, inducing a downward spiral where hardship leads to further destruction. Aside from a few individuals who offer the fox some kindness, we appear to be beyond redemption.

* * *

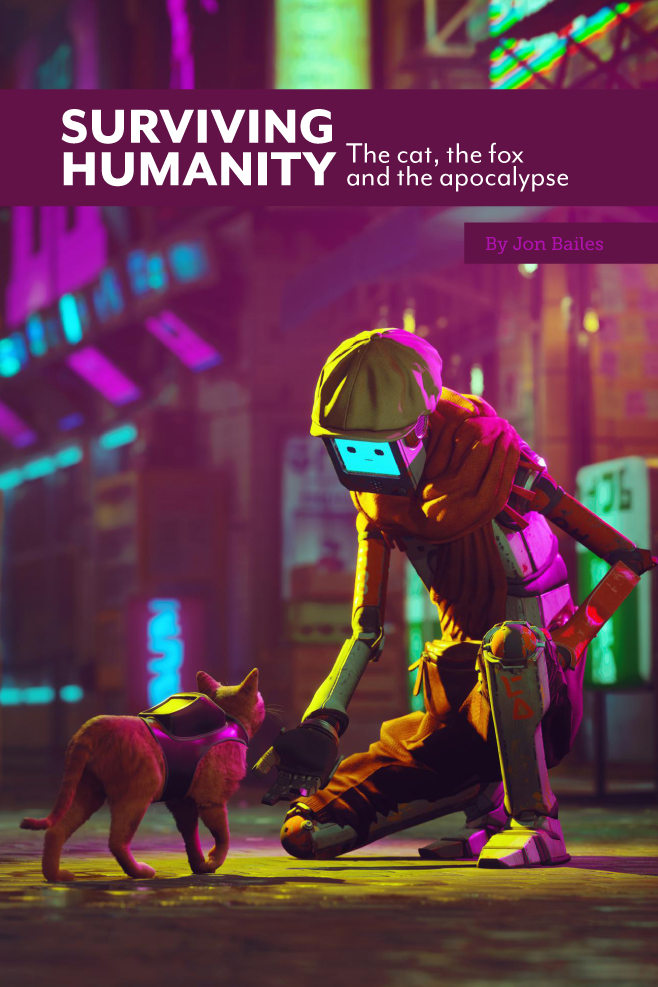

In Stray, humanity isn’t a problem. Some undisclosed time ago, a catastrophe on the surface of the planet forced people underground, constructing a city like a giant sealed bunker. Yet the survivors were wiped out by a terrible pandemic after all, and all that remains are their fossilized buildings and tech. The cat hails from the newly flourishing topside, where it lives an idyllic existence as part of a small feline colony until an unfortunate slip sends it tumbling below. Your only goal is to get back up, to continue enjoying the post-human dawn.

From the cat’s-eye-view, the retro-futurist ruin becomes an assault course or playground, where air conditioning units are stairways to ascend cracked apartment blocks, and dusty green bottles beg to be pawed off a ledge. There is a destructive mischief in being a cat, of course, from jumping on a checkerboard, scattering the pieces, to sharpening your claws on the arm of a couch. But this isn’t the conscious destruction perpetuated by humans, it’s an altogether more innocent interaction with an environment built for other beings with other concerns.

Like Endling, though, the animal is only part of the story here, as a group of androids that outlived their human creators have formed a small community. On one level, these robots, displaying emojis on monitor screen heads like real facial expressions, seem to reflect life in postmodern consumerist societies. Each droid bases its identity on some aspect of “Western” culture without really knowing why, as if they picked roles at random, from a musician seeking inspiration to a drunk slumped on the counter in the local bar, creating the ultimate simulacra – a facsimile of a society that never existed. Their speech and motions are sincere but signify nothing. “I do love the smell of fresh paint,” one droid remarks. “It reminds me of, oh wait. I can’t smell anything. How sad.”

Yet some of these machines are coming to terms with their existence, grappling with philosophy or concepts of art and creative expression. And within their number is a small gang that calls itself the Outsiders, whose singular aim is to return to the planet surface. Whatever has triggered this “desire,” it represents a break from everyday routines, and when the cat does finally open the city roof to reveal the sunlight above, the implication is that the androids will now have to define their own civilization.

———

Jon Bailes is a freelance games critic, author and social theorist, originally from the UK. Having completed a PhD in European Studies, he first wrote about games in his book Ideology and the Virtual City (Zero, 2019), and has since gone on to write features, reviews and op-eds for Washington Post, Edge, Wired, The Guardian, and other publications.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 157.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!