Post-Post-Apocalyptic: Come Along with Me (Part 2)

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #138. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #138. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Peripatetic. Orientation. Discourse.

———

Post-Post-Apocalyptic: Come Along with Me

A version of this paper was originally presented at the CUNY Graduate Center’s English Student Association conference, End Times: Approaches to the Apocalypse on March 12, 2021. Its places will be recognizable to readers of the column. I hope you appreciate this opportunity to return before we take off on new paths beginning next month.

PART 2

If so many apocalypses have happened, and so many apocalypse stories have been told, then at some point, whether it’s that we are built on the ruins of a past end or participating in the post-apocalypse of a cultural that came post- some other apocalypse, we are no longer simply in the aftermath of apocalypse. American culture, it seems, often forgets this. And that’s part of what makes the apocalypse look so different elsewhere.

Understanding apocalypse is, as we’ve already seen, a navigation of politics, war, economics, religion, natural disaster and philosophy at any given moment in a culture’s history. But when it comes to movements of anime, Western audiences and critics alike often reduce to mere images of original meaning, especially when it comes to apocalyptic anime that borrow Christian imagery but contain within them messages from non-Western orders, as Michael Broderick writes.

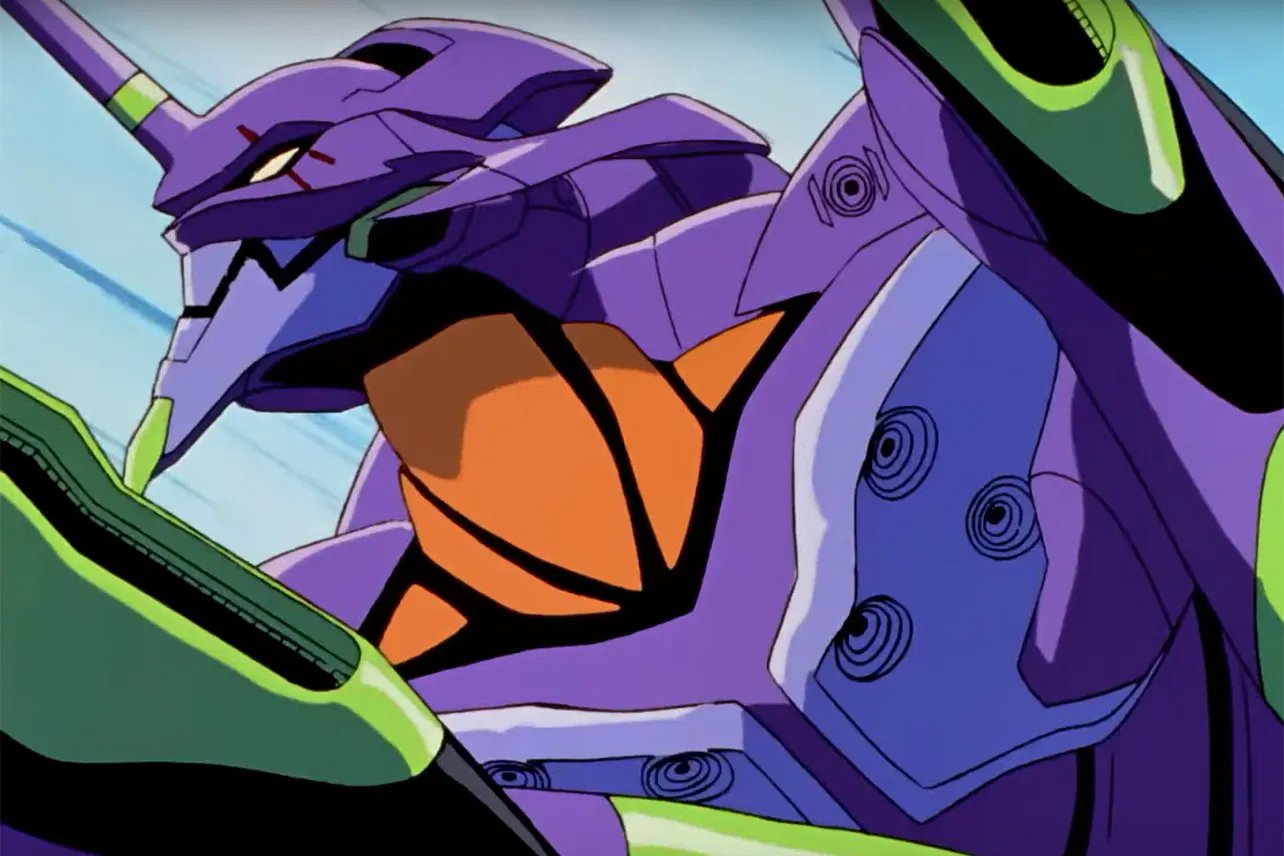

Perhaps because the final entry in this long, long-running series has finally released (at least in Japan), I’ve been thinking a lot about Neon Genesis Evangelion lately. Honestly, I’ve been thinking about it to some extent since I first watched the Rebuild of Evangelion at the start of lockdown. But first.

Evangelion is a 90’s mecha anime about teenagers Shinji, Rei and Asuka, who grow up after some great calamity called the Second Impact destroyed a sizable amount of life on Earth only to pilot giant robots that fight embodied existential threats called Angels. There are also trees of life, an Adam, the Dead Sea Scrolls, a Spear of Longinus and many other increasingly esoteric references to scripture that really are stripped from their own context. Director Hideaki Anno admitted to picking imagery for aesthetic alone and even choosing the eponymous names of the robots because it just sounded cool.

While there are many big fights in robots, to me Evangelion is about rebuilding at the end of everything. In episode 21, former professor Kozo Fuyutsuki laments to his former student Yui Akari over the loss of autumn. He holds a nostalgia for what can’t be rebuilt. Every day is the same without the fall of the leaf. There are no seasons, few cicadas left. And the Anthropocene could be characterized by this stillness: the stillness of Japan after the Second Impact, the approaching stillness of our ocean currents, the stillness of living indoors with no social gatherings, the stillness of suddenly losing every structure you once kept time with (Notes from an Apocalypse). It’s been commented on how depictions of what would become Millennial and Gen Z characters speak with great resonance to those of our time. And video essayist Pause and Select has noted that Evangelion is extremely Lacanian, as the show takes great strides to represent interiority and foreground the struggle of self and identity. Shinji, and all of the other pilots, will never know the blue oceans or the changing seasons, but they grow up in a world desperately clinging to the normalcy of movie theaters.

The Rebuild series is a whole lot of things: remake, adaptation, retelling and continuation of the show all at once. While the antagonistic relationship between author and audience is perhaps the movies’ most compelling feature, what gets me stuck thinking about them here is how they mimetically function as a post-post-apocalypse to what was already an incredibly resonant depiction of the post-apocalypse we are currently living through – if you choose to believe It already happened.

The differences in the show and movies are at once immediate and seemingly small. Like how the ocean is a different color – the red it took on after the apocalyptic conclusion of the show. It first seems like the studio retconning their work since the ending was unknown to every one of them when the first episode was produced, but these inconsistencies pile up and then suddenly big moments are rewritten. Oddities occur and, halfway through the film series that’s taken nearly two decades to complete, everything changes – the specifics of which are less important than the form that this takes both narratively and structurally.

I remember reading something the director wrote for the Blu-ray release of the first movie, which I only rented from the library and couldn’t get in time. But Anno says that he wanted to make an Evangelion series that would speak to kids who didn’t watch Evangelion growing up. Which is kind of hard to believe would be possible in Japan given its incredible popularity, but I think this intention is notable. So far, in the Rebuild series, more apocalypses have apocalypsed. But unlike before, this is not a closing. The characters have to live in that world, and it makes clear that Shinji, who represents the audience that holds the original story dear and captive, that he’s putting this world and its people through pain. All for their story to be told again without an End this time.

“Instead of halting at denouement, apocalyptic anime glimpses beyond the cataclysms of radical renovation,” writes Michael Broderick. But post-post-apocalyptic might be a limiting name for whatever this new genre of zoomer apoc fic is. If what takes shape after the end is freed from what was before, the name doesn’t suggest so. But, then again, neither does Adventure Time, where the remnants of bombs and video games alike are sites of nostalgia.

***

And so, we arrive at last, at Adventure Time, on whose apocalyptic stories I literally grew up. There are 280, mostly 11-minute episodes of Adventure Time. The first one aired when I was in seventh grade, the last when I was a junior at university. Its appeal is often described in a single word as nostalgic, though my relationship with it as someone who was a child and not a critic when the show aired has to be different. I am not nostalgic for the childhood things that Adventure Time evokes as much as I am nostalgic for Adventure Time.

Video essayist Grace Lee describes Adventure Time’s post-post-apocalypse as “a future where life as we know it has ended. But, of course, that isn’t to say that life has ended.” Remnants of Ooo’s past are scattered about, indicating civilization – and capitalism – once occupied the same land. In “Dark Purple,” a soda company’s kidnapped, mutant labor force is described as “weird, ancient ways,” while in “Ocarina” Jake gives a lesson on colonialism in the distant past before trading the functionally obsolete deed to the tree house for an ocarina without any holes in it.

Heather Smith has called Adventure Time “a pop art version of the end of the world.” But Adventure Time is also. It’s ambivalent. A melancholic undertow grows among the rubble of Ooo’s zany futurity, a current of mutability that crashes into the medium, propelling character and drama forward. And this – transformation – is a theme of the show. “From shapeshifting to temporary mutation to complete regeneration, the process of becoming almost something unrecognizable” is ever-present, which puts change and constant in some sort of harmonic tension with each other. But whether it’s the catalyst comet, Finn’s reincarnation, or the very apocalypse itself, Lee argues “what Adventure Time’s cycles seem to suggest is the potential for growth by way of return.”

There is even a confrontation with the people we, too, were. At its conclusion, Finn and Jake, Marceline and Bonnie, Simon and Betty are not the people they once were, as much as I am not the person I was when their stories began. In 2018 that felt like a loss, but unlike the post-historical apocalypses of our media landscape and unlike the spiteful Evangelion, the story does end. Adventure Time’s ending even philosophizes about these endings, never more so than in “Time Adventure,” whose lyrics comprise a lullaby that keeps the cosmic forces of discord at bay and a poetic rumination on the lives that continue past the inevitable end of our spoken words.

The shows final moments reframe the entire series in legend, myth, and historical memory. Schermy asks the King of Ooo what happened to Phil and Jake and BMO says well, they kept living their lives. And that, right now, sounds like the most mathematical future we’ve been shown.

———

Autumn Wright is an essayist. They do criticism on games and other media. Find their latest writing at @TheAutumnWright.