Post-Post-Apocalyptic: Come Along with Me

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #137. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #137. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Peripatetic. Orientation. Discourse.

———

A version of this paper was originally presented at the CUNY Graduate Center’s English Student Association conference, End Times: Approaches to the Apocalypse on March 12, 2021. Its places will be recognizable to readers of the column. I hope you appreciate this opportunity to return before we take off on new paths beginning next month (or the month after part two is published).

PART 1

For the past couple of years, if you asked me for podcast recs, one of the first things I’d have offered you is Fall of Civilizations – a history podcast about the ends of many others’ timelines. Hosted by author Paul M. M. Cooper, every episode is set in a different time and place, from the collapse of the first Sumerian cities, which are also some of the first cities, to the ends of the Roman empire . . . twice, to an apocalypse that took place on only 63 square miles (163 sq. km) of land, on Rapa Nui, in the same millennium I and most of you must’ve been born. The big questions connecting each episode are: “What did they have in common? Why did they fall? And what did it feel like to watch it happen?” They’re questions we can ask about many times and many places, ones that we’ve even begun asking of ourselves.

These stories of apocalypse have accompanied me for the past years as my fear met certainty which turned to acceptance that, while I now know for certain I am no longer of the last generation, I may still know The End. That all-encompassing grand closing that is everything we’ve said of it and that words could never justify, because it is all the words that come before “the end” that linger in us when a story we love ends. And yet knowing the apocalypse is only stories – many, many more stories than the 12 in Fall of Civilization’s backlog – doesn’t alleviate the contemporary sense that this end is not like the others. Whether you’re a historian or theologian, “it has,” as Mark O’Connell writes in Notes from An Apocalypse, “always been the end of the world.” So, what is that instinct I, and I’m sure some of you have, that this isn’t going to go like any of the stories we’ve been told?

I don’t think it is impossible, given the development of apocalypticism as a belief and literature, that this moment – and its fictions – are drastically different from the nigh apocalypses of yore. In The Sense of An Ending, Frank Kermode writes “Apocalypse and the related themes are strikingly long-lived; and that is the first thing you can say about them, although the second is that they change.” And how they have changed. St. Augustine writes that Christians three centuries before him were “consumed with apocalyptic fervor, [believing] themselves to be living in the ‘last days’ of creation.” “And,” he remarks, “if there were last days then . . . how much so more so now.”

Apocalypticism – in whatever mode of fiction we want to call it – is intrinsically tied up with Christianity. Roslyn Weaver writes that, with its origins in an oppressed religious minority, the apocalypse was a critical framework that subverted oppression in its time. It imagined the collapse of what were unshakable systems. But, as no small number of critics and scholars have noted, the apocalypse’s radical origins are, along with the original meaning of the word, antiquated. Weaver argues that “some secular narratives subvert the original context of apocalypse as a language for the oppressed to instead use apocalyptic rhetoric to dominate and justify the persecution of minority groups.” And I would disagree with her on two accounts. While the interdisciplinary field of apocalypse criticism (apoc crit, if you may) maintains a distinction between Biblical and secular apocalypse, I don’t think this is such a useful distinction, at least not now. Which is my second point, that not only is the contemporary understanding of apocalypse different, but apocalypse itself may also be something else. And so, in criticism of apocalypse fiction written outside of academia in the past decade, the generic and subversive are reversed. And why should we think not? Have you seen what every man with the power to make a blockbuster movie or AAA game thinks, or rather hopes, the collapse of civilization will look like? Games critic Grace Benfell, with the Biblical apocalypse in mind, describes the state of the genre in the current millennium: “apocalypses are often a product of our inability to create a better world . . . All communities will eventually decay. Even if they don’t, they must fight off invasion from all sides. The collapse of society brings out who we really are and it is monstrous. The end of western civilization is the end of everything.”

Or almost everything. The fulcrum of my thinking around apocalypse fiction since last fall has been Marxism. Specifically, the first chapter of Mark Fisher’s 2009 book Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Fisher introduces the eponymous theory with film criticism, literally amending its definition:

‘capitalist realism’: the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible to imagine a coherent alternative to it. Once, dystopian films and novels were exercises in such acts of imagination – the disasters they depicted acting as narrative pretext for the emergence of different ways of living.

But no more. Even the films that speak against capital are still reeling in a tired, decrepit future with no history of its own. And I think Fisher was onto something with this particular mode of critique. The apocalypse can be quite persuasive. Rhetorician Stephen O’Leary even suggested that the apocalypse is a rhetoric of its own, of time, evil and authority. And Weaver explains that apocalyptic fiction “must convince its hearers that they are, indeed, living at the end of history.” Which is its own apocalypse that we don’t have time for.

Though it was as painfully true in the last century, it’s only now that we seem to identify America itself as the urtext of its own apocalypse fiction. And I mean the ideal as much as the land itself, a place for new Christian minorities to seek salvation. Writer Heather Smith calls this a “post-apocalyptic dream America.” In her influential criticism of Adventure Time, she writes: “Historian Paul Boyer has argued that this 17th century idea of America as a promised land lasted much longer than the Puritans themselves managed to. It persists as vague ideas that America is somehow a special place, with a redemptive role in world history.” America has always been in apocalypse but bereft of historical narrative in the ever present it is tempting to sensationalize our own experiences, to pretend that we discovered apocalypse when European’s first imports were only apocalypses of diminishing sizes.

Lest we forget nuclear fiction. Nukes are everywhere when we talk apocalypse in America, to the point that they are no longer anywhere at all. (Well, hopefully someone knows.) But I think Smith puts it nicely: “America, it seemed, worked through the issue of having bombed Japan by generating an endless number of stories were [sic] America was the bombed, not the bomber.” She claims that 20th century reality split into two separate timelines. An off timeline where people who could’ve use nuclear weapon continually did not, and a bizarre future where they did. Thus, the nuclear apocalypse, with its radioactive wastelands and mutant monsters became the preeminent realm of American futurity.

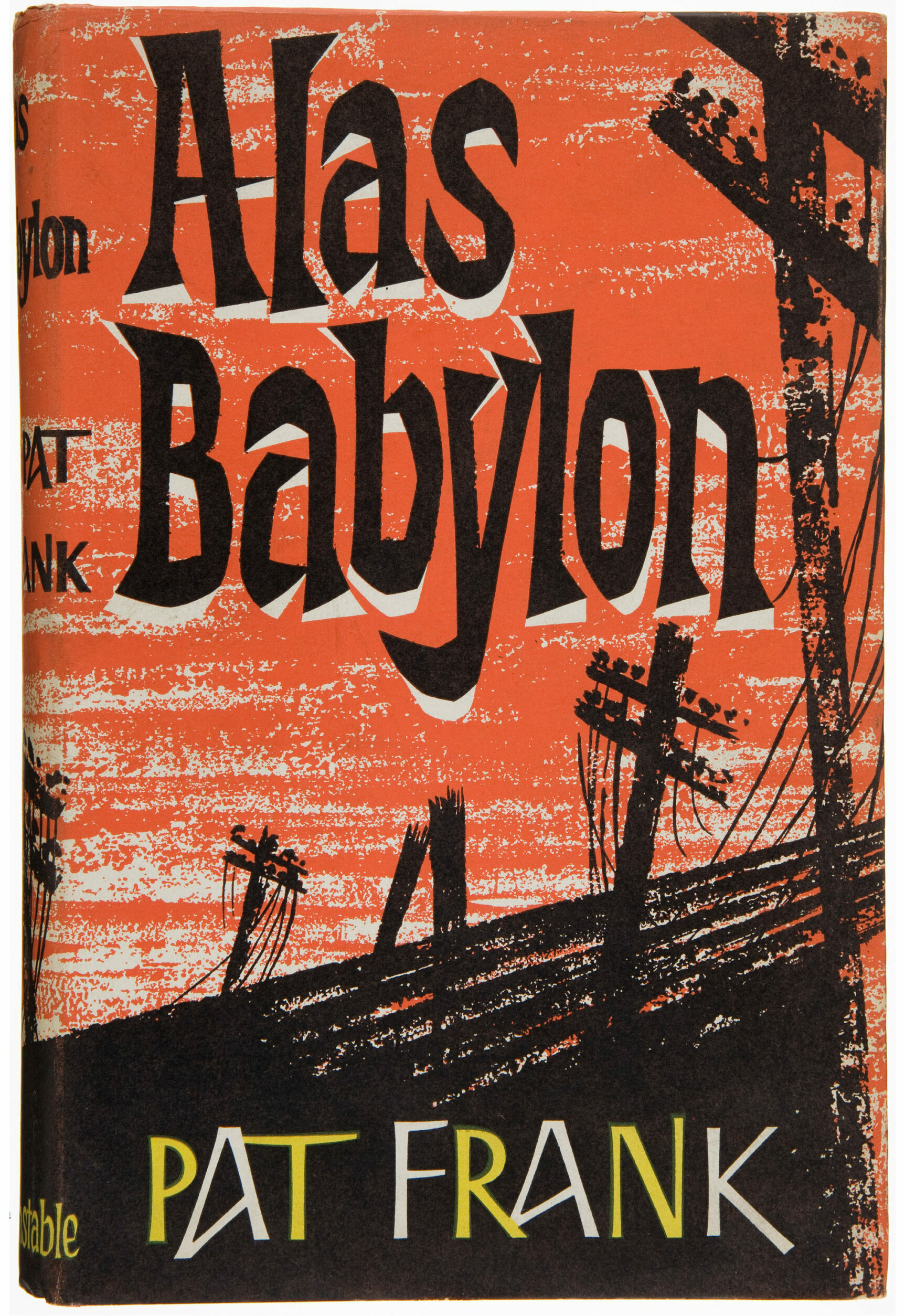

Written nearly a decade after what Smith cites as the first nuclear novel (Shadow on the Hearth), Pat Frank’s Alas, Babylon is perhaps the most enduring of those seminal texts. Published in 1959, the novel is about if America won the Cold War – and mutually assured destruction. It’s set in a fictional central Florida town called Fort Repose, which is based off of the nonfictional central Florida town Mount Dora, which is less than an hour away from where I went to school (though where I went to school is, in this timeline, a crater).

When I first read Alas, Babylon, the way I envisioned this particular future looked a lot like what I remember from high school of early seasons of The Walking Dead. The main character and what often feels like a painful, painful self-insert, Randy, is a gruff veteran and alcoholic living on the land a great-something of his settled. And the rest of the cast is, well, the book opens on Florence, who lives alone at her age only because she is unmarried and will remain that way. Her main character traits are that she’s gossipy and because Frank really wants you to remember, fat. There’s the Black family that Randy apparently treats really well even though they’re only there because they can’t afford to live anywhere else since he won’t pay them more (and their use to the plot is that they are . . . useful Black people). There’s Elizabeth, an upstart, independent women who just becomes partnered and sidelined to Randy. The hysterical sister-in-law who is, like all the women, a natural caretaker. There’s a banker that completes suicide because all the money is worthless and a young fighter pilot who is so insecure about his masculinity that he accidentally bombs civilians and kicks off a nuclear war. But there is also a queer librarian in what seems like the oversight of a straight man.

Frank uses armchair analysis of the political landscape he adapted to make commentary on the Cold War and a wide cast of characters to critique consumerism, citizenship, gender roles (poorly), race (very poorly) and authority (extremely poorly). As an author insert, Randy’s Catholic-tinged nobles oblige becomes the moral framework. And while the threat of nuclear annihilation can be called the first secular apocalypse, it still holds in its anxious narratives all the revelatory potential of a Biblical one (if we choose to maintain such a grey distinction). Alas, Babylon seeks salvation and finds it in a return to old ways of life. It is not an imagination of the world after capitalism or nations or borders, but a romanticization of the preindustrial. He’s nostalgic for when the religious moral order was not threatened by marketing and, I don’t know, shorts.

Frank uses armchair analysis of the political landscape he adapted to make commentary on the Cold War and a wide cast of characters to critique consumerism, citizenship, gender roles (poorly), race (very poorly) and authority (extremely poorly). As an author insert, Randy’s Catholic-tinged nobles oblige becomes the moral framework. And while the threat of nuclear annihilation can be called the first secular apocalypse, it still holds in its anxious narratives all the revelatory potential of a Biblical one (if we choose to maintain such a grey distinction). Alas, Babylon seeks salvation and finds it in a return to old ways of life. It is not an imagination of the world after capitalism or nations or borders, but a romanticization of the preindustrial. He’s nostalgic for when the religious moral order was not threatened by marketing and, I don’t know, shorts.

But what of another timeline, one where we remember bombs were used? We can’t really talk about apocalypse fiction without talking about Japan.

———

Autumn Wright is an essayist. They do criticism on games and other media. Find their latest writing at @TheAutumnWright.