Talking Splats: An Interview About Insect in Films

“Let me get this straight,” I say bluntly, my excitement getting the better of me. “You do insects, not spiders. Does this mean we can’t talk about Eight Legged Freaks or Arachnophobia?”

“That’s correct! Entomology is the study of insects specifically,” the man with the Ph.D tells me. “Though I do like talking about spiders and other arachnids, I am by no means an arachnologist.” The shifting in his chair suggests he saw the disappointment in my face, so he reassures me. “I generally think all invertebrates are pretty cool, since they’re so structurally different from mammals and other organisms that have a backbone.”

I met this man online through some friends. At first, I thought he was another gaming nerd like myself, just one that happened to hold the world record speedrun time for StarTropics on the NES. After a long conversation about videogames and superhero movies, I also discovered he was an entomologist by degree. It hit me that I should have realized this, given his online handle: BugDoctor. He asks we not use his real name, due to concerns about interviews like this hurting his academic career, so that’s what I’ll call him.

To see where our interests met further, I proposed we do an interview to discuss his specific field and how it was portrayed in science fiction movies. I had critically important questions like, “What is your favorite bug?” and “Why would someone have a favorite bug?”

“It’s hard for me to pick a favorite bug. To start things off,” he says in a very this-will-be-on-the-test voice, “I will have you know that not all insects are bugs!” His enthusiasm throws me off as much as his premise. “The ‘true bugs’ are a particular taxonomic order called Hemiptera, which are often confused with beetles due to the protective cover they have over their abdomen which looks like a beetle’s elytra, their shell.” Thankfully, he is willing to simplify this. “So, not all insects are bugs, but all bugs are indeed insects!” I blink a few times and then force myself to nod in pretend understanding.

“Back on track though, I have always had a fondness for Coleoptera, the beetles. They are just so incredibly cool looking and also ridiculously diverse! Did you know that about a quarter of all described animal species on Earth are beetles?”

I clear my throat quickly to avoid answering and shuffle my notes around, searching for a good follow-up question. “Do other people with doctorates consider you to be weird?”

“They do,” he answers honestly, “but usually because I’m just a strange person in general!”

I remember then why I arranged to speak to the BugDoctor and seek to point us in that direction. “So in Avengers: Infinity War, Thanos snapped his fingers and the Russo Brothers confirmed that half of all animals disappeared along with the people. How would the world be affected if half of the insect population vanished when the humans did also? It would have to be just as weird when they all re-appeared five years later in Endgame, right?”

He takes a moment to respond. “Ah, ‘The Snap,’ yes,” he says, as though it were a name he hadn’t heard in years, contemplating that time in history. “It would certainly have strong repercussions throughout our world. The good thing about insects is that they are in such high abundance that having half of them disappear would still leave quite a sizeable population capable of reproducing and flourishing, except for rare and threatened species which may just go completely extinct in the aftermath.” The answer lacks the same drama the movie presented.

“The ability for certain insect species to persist through such a catastrophe would also vary between ecosystems.” I nod, making a note of his essential ‘I don’t know’ response. “That being said, many of the remaining insects would likely continue to thrive; some populations may even have a sudden outbreak as a result of their predators disappearing as well. Pollination of crops and plants would pretty much be guaranteed to take a massive hit, significantly affecting our food production.” His promise of a famine sounds enticing. I think he would elaborate, but then he says, “But hey, the remaining people sure would be glad about the lower numbers of mosquitoes!”

I chuckle, wondering if this interview was the best idea.

“When they reappeared five years afterward, it would have another drastic effect for sure. Any sudden population spike like that would have a huge impact on the resources that those creatures feed upon, and so there would likely be another crisis. You just can’t win, man!” This is the answer I’m waiting for, to know that the solution in this case, bringing everything back, would cause just as many issues.

“That’s excellent, so they would be screwed either way,” I say, too enthusiastically to stick it to Marvel, perhaps. He looks at me oddly. I need a new question.

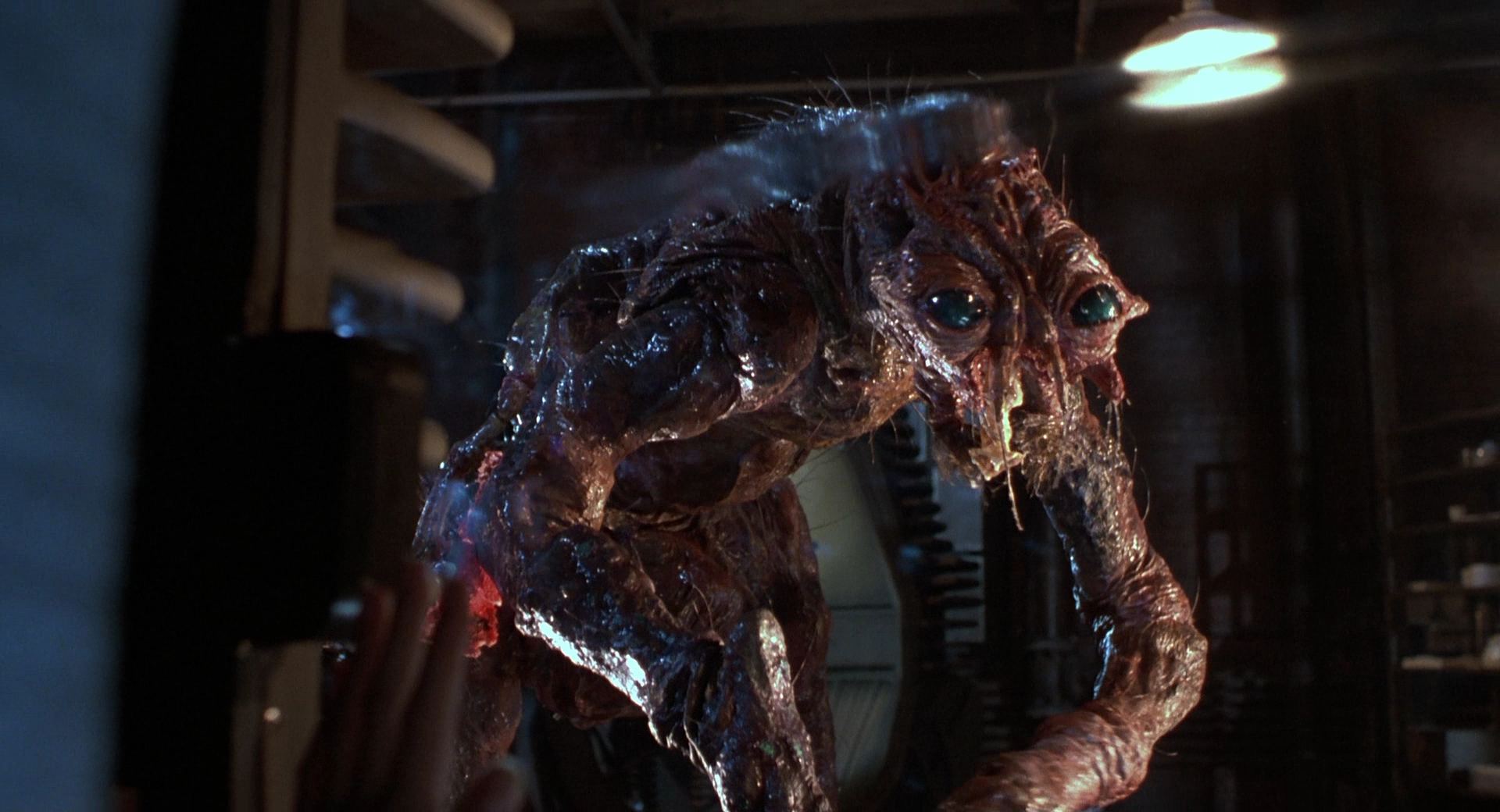

“I was a huge fan of the movie The Fly as a kid, but now I’m wondering what you think about that film. Other than what I imagine is an obvious love of Jeff Goldblum,” the reason everyone should watch the film, “what do you think a person turning into a human-fly would go through?”

“For the sake of simplicity (and fun!), let’s just assume that Goldblum’s functional body parts would transform into their insect counterparts. Since insects do not have an internal skeleton like we do, Goldblum would probably have all of his bones restructure into chitin and migrate to the outside of his body to become an exoskeleton, which I imagine would be excruciating.” I realize my subject might be into some weirder shit than I thought. “His muscles would have to switch their attachment so that they pulled on the exoskeleton as well, so that whole rearrangement would be a terrible process. Goldblum’s eyes would split into numerous facets and his vision would become ‘pixelated’, for lack of a better term. They’d also probably take up a large amount of real estate on his head! Wings would sprout from somewhere on the middle of the back, but then behind those wings two knob-shaped structures called halteres would also pop out, which are used exclusively for balance during flight. His legs would fall off,” he says, and my eyes widen. Perhaps the movie hadn’t quite done it justice. “But then he’d sprout two pairs of appendages on his torso underneath his arms, since all insects’ true legs are attached to their thorax. Geez, there are a ton of other weird things that would happen during this transformation! Don’t even get me started on the genitalia!” No, we certainly will not.

“Another hopefully less painful possibility is that he would undergo pupation,” a word I dare not type into a search engine, “which is a key component of development in the housefly life cycle. To do this, he would hide himself away inside a giant fleshy human-sized pupal casing. Once Goldblum was safely inside his pupa, his current body would essentially liquefy and drastically rearrange.” I’ve cut some of this description, dear readers, because it is about here that I felt my lunch beginning to return. “It’s a process known to many as metamorphosis. Once this process was complete, he would emerge as the adult form of a fly, except much, much larger.”

“Take your pick,” he exclaims cheerfully. “Personally I like the first option because it sounds more excruciating!”

I wait for my stomach to stop spinning and clear my throat. “I don’t think I will,” I say, “nor will I be watching The Fly again for a while.”

“It’s hard to have a conversation about bugs without bringing up Starship Troopers,” I say. “If the world had to go to war with giant bugs, who would win? How do you think the Brain Bugs works?” And the most important question, “are there bugs that actually fart harmful projectiles?”

“This is an interesting question,” he says with a smile. “If we went to ‘war’ with insects, you’d have to assume that they’re capable of organizing themselves and focusing their attacks on us as a group, which suggests they’d function as a colony,” I feel this response shows his bias in the coming war. “This is somewhat alluded to in Starship Troopers in which the Brain Bug seems to act as a ‘queen’ of some kind, while the other types, like the warriors, tankers and hoppers function as the other castes (soldier and worker ants, for instance). The name of the Brain Bug implies that it can psychically control the other castes, but a more realistic possibility is that it exudes some sort of order on the other bugs using pheromones, which is what ants, bees, wasps and other colonial insects use extensively to communicate,” but the psychic abilities are much cooler and less messy. “So, maybe it takes all that brain matter it sucks out of the skulls of humans and converts it into pheromones? Damned if I know,” he admits, meaning I was right about the telepathy.

“As for the second question, there sure are!” I didn’t expect to hear a professional get excited about insect flatulence, but here we are. “The best example of a “harmful insect fart” would probably be the bombardier beetles, members of the ground beetle family Carabidae that fire superheated chemical mixtures out of the end of their abdomens like a shotgun. It’s not a projectile really, but instead a boiling hot spray that explodes out of their ass. This is used mostly to deter predating insects, but can actually kill them in some cases,” a fact that makes me think people are still sleeping on how good Starship Troopers is.

I want to give BugDoctor a softball question. “Most people who saw Honey, I Shrunk the Kids when they were younger wanted to ride a bee. How would that work out? Do you think we could really befriend an ant?” Some of my own prejudices then slip through. “Also, why are scorpions dicks in every form of media?”

“I mean, if we were the proper size to saddle a bee, you’d have to hold on pretty tight to avoid falling off,” he says, a fact I expect anyone could have come up with. “Insects are incredibly maneuverable when they’re in mid-flight, and any sudden turns or dips could be enough to shake you off or maybe even break your bones from whiplash. Luckily, bees are super hairy, and those hairs are also plumose, which means they have a branched sort of structure to them.” It is possible. That’s all I want to hear.

He moves on to ants and their friendships with other insect species. “There are very small insects called aphids, which feed on plant fluids with their long beaks and produce a substance called honeydew which is secreted out of their,” he pauses uncomfortably, “well, butt.” Is there not a more scientific word for butt? “Honeydew is loaded with sugars, and certain ant species will actually consume it as a source of nutrients. In return, they protect aphids from other predators since they are such a valuable source of energy for the ants. This ‘friendship’ is called mutualism, a symbiotic relationship between two species that benefits them both.” I could bring my ant friends Oatmeal Cream Pies also. “That being said, this relationship would have taken thousands of years to establish, and though I’m sure that there could be some sort of similar mutualism between humans and ants, I wouldn’t hold my breath,” he says, smashing my hopes.

Not being an arachnologist, he hesitantly follows this soul-crushing with a defense of scorpions. “It’s probably simply because they look frightening.” You think? “Pincers, eight legs and a venom-loaded tail are not things that give the impression of friendship.” This confirms my suspicions that they are all dicks.

I move on. “Marvel’s Ant-Man supposedly communicates with ants through a cybernetic helmet that transmits and receives psionic, pheromonal and electrical waves. Would this work? Is there any way we could communicate with insects? With a power like that, should we? Would we want to? Would they have anything good to say?”

“In theory this could work,” he loves giving answers as remote possibilities. “With the right pheromones, it may be possible to cause ants to aggregate around a pheromone source, follow a trail, or behave in a certain way, so that factor of the helmet is somewhat believable.” Meaning Ant-Man is a much cooler hero than anyone gives him credit for. “’Electrical waves’ is sort of a strange term, but certain insects, as well as other animals, can respond to the presence of electromagnetic fields, so if that’s what was being used, then it could potentially help Ant-Man to control his hexapod friends! As for psionic energy,” he says with a shrug, “hell if I know! That shit is nebulous at best.” Well, two out of three ain’t bad.

“It would be pretty tough to communicate with insects in any sort of fashion. We’d simply have to use stimuli that they could understand and react to.” Like complimenting them, telling them they’re having a nice antenna day? “But I doubt that they’d be able to ‘talk’ back to us in any significant capacity.” Okay, got it, no long philosophical conversations about the ant working class.

“Godzilla fights a lot of insect Kaiju,” I say assuredly. It’s time to bring out the big guns. “Should we be worried about bugs finding nuclear waste? Do any of his enemies like Mothra, the MUTOs, or any of the others seem to be pretty accurate with their attacks?”

“If insects find nuclear waste, they would probably just die from it and wouldn’t become overgrown to the point where they could destroy buildings. In fact, if an insect did become that size, it would simply collapse under its own weight and wouldn’t be able to breathe properly, killing it,” Dr. Downer says. “Godzilla wins!”

“Mothra,” he says, disappointed, “is not accurate at all in her attacks. Moths don’t really attack anything, and instead just try to avoid being attacked themselves.” It seems fair, but I let him keep going. “In King of the Monsters, Mothra is shown dive-bombing things, but the closest that a moth gets to this in reality is intentionally falling into a tumble to avoid being eaten by a bat.” This sounds less cool. “There are (fortunately) no moths that can fire energy beams from their antennae. They don’t sting, and they’re also not associated with magical fairies…at least, not to my knowledge. The order Lepidoptera, under which the moths and butterflies are classified, literally means ‘scale wing’ so these critters DO have scales on their wings that can fall off; Mothra has been shown to use these to her advantage occasionally.” So, Mothra is bullshit? “I believe there are Godzilla films that show Mothra larvae producing silky cocoons, so that is accurate,” he says. Fair.

“As for the MUTO,” he adds, “what the heck are they supposed to be anyway? They almost look like enormous cockroaches.” I guess everyone really does hate the 2014 film. “I remember they generate an electromagnetic pulse that shuts down machinery, which as far as I understand is something insects can’t do.” That’s why they’re mutated, of course.

“We see so many films with giant insects,” I say. “If peppermint oil and charcoal will keep normal bugs away, would giant amounts keep giant bugs away?”

“That is a very good question, Mr. Wilds. Only science holds the answer!”

“Why do I get the impression you’re lying to protect the bugs?”

He doesn’t answer, so I move on. “The Mummy made me afraid of scarabs. What did they get right about that? There were also some scary beetles in the movie The Relic. Why are beetles so scary?”

“The Mummy got nothing correct about scarabs, except for the fact that the Egyptians of old had a fascination with them. Scarabaeidae is a family of beetles that primarily feed on plant life and fruit. Though there are a few that are known to feed on carrion,” that still sounds scary, right, “scarabs certainly do not make it a habit to bury themselves under living human skin and run around in your body.” Oh thank god. “They also can’t move nearly as fast as they do in that film, so yeah, not much accuracy whatsoever, at least behaviorally.” I still think they’re terrifying enough. He does concede that the film got the appearance of the scarabs correct.

“I personally do not find beetles scary at all, and people, in general, should not be afraid of them either,” he reassures. “The most that a beetle will often do is simply give a small pinch from a bite if you really aggravate them, and even that’s rare.” He notes a few exceptions, like the bombardier beetle (which he doesn’t bother telling me how to identify) but is otherwise insistent that “beetles are completely harmless.”

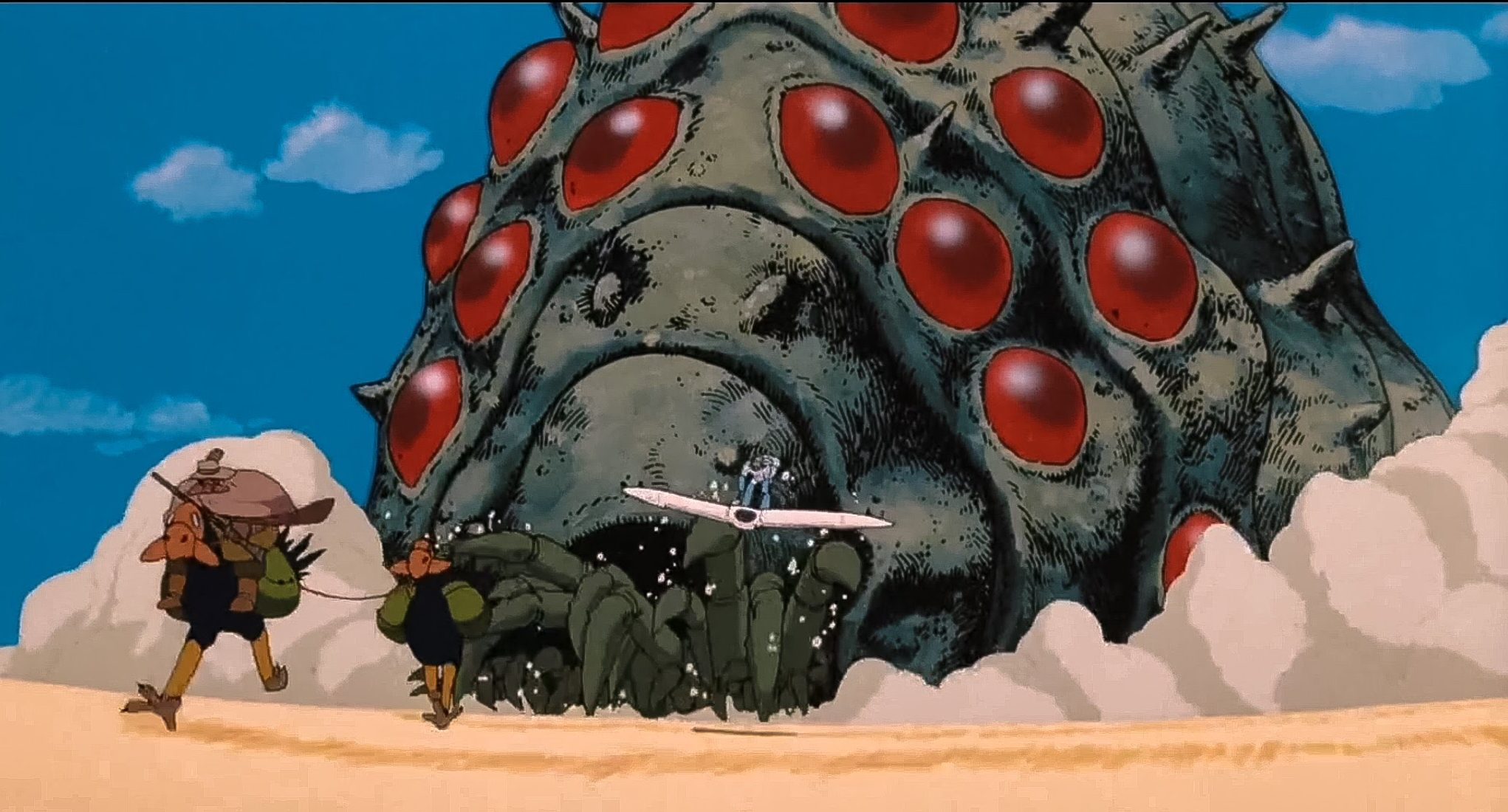

Like most of my interviewees I attempt to trip up, my curveball question revolves around anime. “Films like Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind make insects (Ohmu) seem important to rejuvenating the Earth. Is anime right?”

“This is absolutely correct,” he says firmly, “Insects have very important roles in the myriad ecosystems they inhabit, and this includes things like decomposition of decaying matter and nutrient cycling in soils.” He describes his precious bugs as Earth’s janitorial staff. “Additionally, a ton of insects act as pollinators as they take pollen from one flower to the next while they forage. Bees are the most common example here, but many different butterflies, moths, flies, beetles and other insects can also act as pollinators to various degrees. Without insects to facilitate cross-pollination, a lot of our most beloved crops just wouldn’t be able to persist, as well as many other types of flowering plant life.” He threatens that insects could take away my Subway sandwiches. “On a serious note, it is important to protect our six-legged friends. Though many act as pests, insects generally provide a variety of important services that benefit their environment. Think about that the next time you consider stomping a beetle or swatting a moth away!”

“Knowing everything you’ve learned about insects, what would be the most terrifying one if they all suddenly grew to be the size of small cars?” More importantly, I ask, “how fucked are we?”

“If they grew to the size of small cars, and actually were able to survive as such (even though they likely couldn’t, as I mentioned), there would be a LOT of terrifying ones,” he says, solidifying my nightmares for the next week. “Can you imagine a mosquito that was able to drain the entire source of blood from your body and not even be full from it? Or a praying mantis snatching you up with its raptorial forelegs?” Its what? “Chowing down on you while you were still alive? Geez, there are so many possibilities! If they all grew to be that size, they’d all be pretty terrifying to be honest.” Somehow, he’s still fascinated by everything he suggests.

“Cicadas also seem a bit terrifying,” he continues.

This is a fact I’m all too familiar with, living in the South. “It might be because of the sound they make, like that villain on The Flash. A more general question: why are aggressive insects in movies, big or small, always hissing?”

“The great thing about cicadas is that they are actually not frightening at all. I often refer to them as the idiots of the insect world,” he says, which seems rude. “The larvae emerge from the ground, moult (shed their skin) to become their adult form and then are almost entirely focused on mating at that point. They spend a lot of time sitting on branches, and they often can’t even do that correctly so they’ll just fall off and onto the ground like stupid morons.”

“The sound they make is a mating call, and it’s only the males that produce it! So, it’s not a threatening noise at all,” he says, and I think about how much movies have lied to me. “That being said, many animals (not just insects!), produce a warning noise to try to startle threatening critters or humans and save their own skin/exoskeleton.” BugDoctor already has another unsolicited example chambered for me. “The Madagascar Hissing Cockroach makes an audible ‘hiss’ when it senses a threat. This sound is produced when the insect forcefully pushes air out of its tracheae,” he says, which I didn’t know bugs had. “This can scare away a predator, even though Madagascar hissers are completely harmless.” Harmless or not, they’re still roaches, I think. “The fact is, hissing noises are scary because that’s exactly how they’re designed to be.”

“I don’t think anyone likes cockroaches,” I say.

“I like cockroaches! Except the ones in Joe’s Apartment, they’re fuckin’ annoying.”

“For me, I think it was the bad guy from Men in Black.”

“Oh Edgar,” he says, as though he knew the space roach personally, “I think it’s just because MIB was going for that sort of ridiculous style rather than a truly scary atmosphere! It’s hard to believe that was Vincent D’Onofrio.” An accurate statement and one of the few things we agree on.

“Slither is a good movie about slugs, and there is also Night of the Creeps,” I say. “Why do we usually see them poised as alien parasites? Why do sci-fi films love cosmic insects?”

“Sci-fi films love space bugs because it’s easy to make them the stars of the movie,” he says making a nudging motion and laughing at his own joke. “Eh? Eh?”

“I think you should stick to Entomology and I’ll do the writing, jokes and all.”

In seriousness, he says, “I’m not really sure why slugs are often portrayed like parasites. I think it’s the only way to make them seem threatening to any sort of degree, because they move so damn slow and are absolutely harmless to us. The thought of having a big ol’ banana slug stuck to the side of your head is…” absolutely terrifying, I finish in my head. “To my knowledge, there aren’t any that act as parasites, and they all feed on plants and fungi, so no worries.”

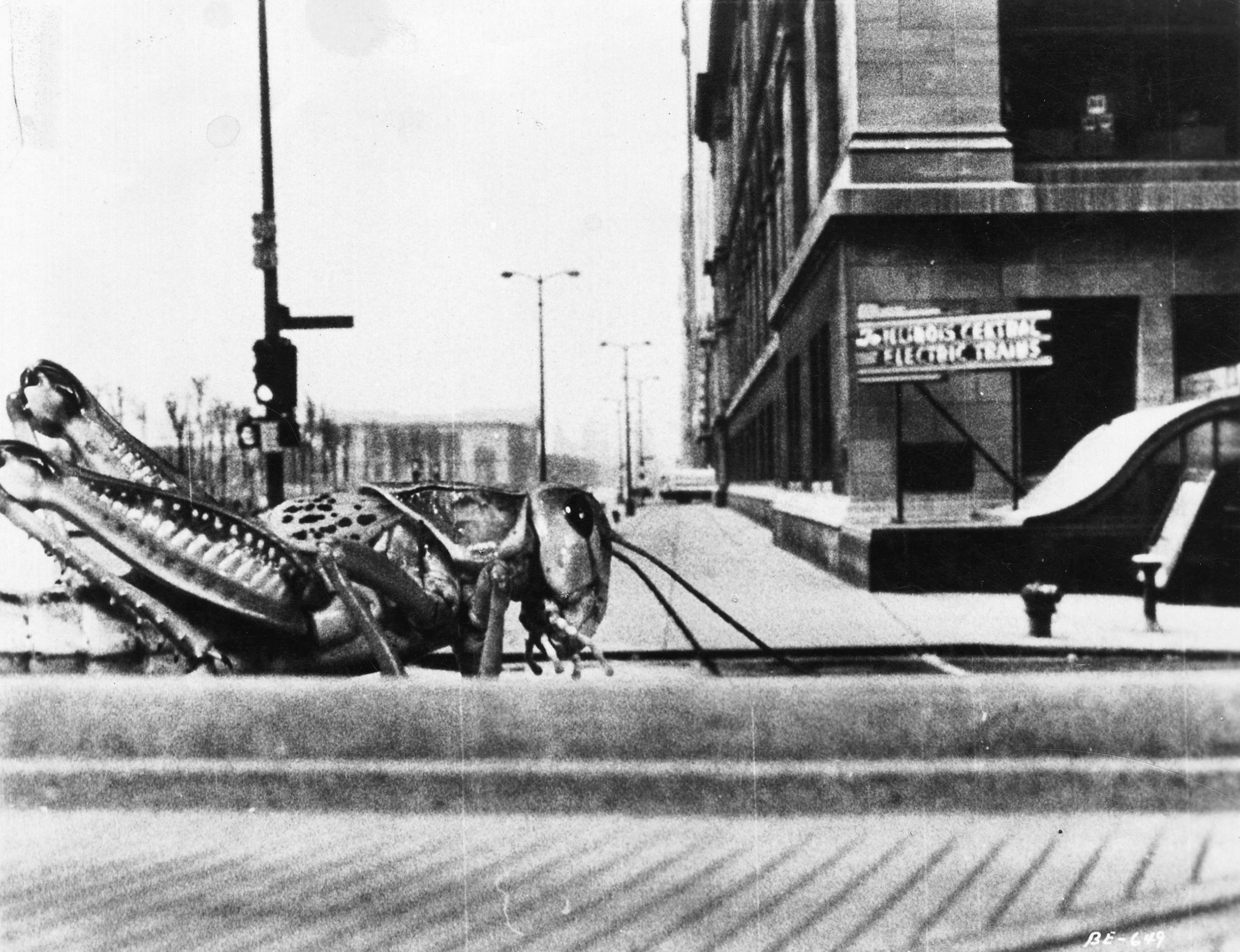

“Locusts are creepy too, especially since they also make a weird noise and eat all of our food. Would there be any food left if locusts were giant?” I say. “The Beginning of the End is a good example of a lot of the bad (but fun) 1950s giant insect movies.”

He acknowledges it would be a significant issue. “Locust swarms, which are (fun fact) actually called plagues can defoliate entire fields of crops that they land on and ruin the lives of farmers. That being said, this doesn’t often happen anymore as a result of proper control of grasshopper populations, unless there’s an exceptionally large outbreak.” If grasshoppers were enormous, he suggests, “our control measures wouldn’t work nearly as well as they do right now, and they would easily obliterate any crops they invaded thanks to their increased appetite. We’d probably have to use rocket launchers to kill them and would have to eat the locusts themselves instead of our grown vegetables.” A bleak future for sure, that I doubt would taste like chicken.

“Monster from Green Hell explores Africa and giant wasps. Are wasps really just dicks with no purpose?” I ask. “Would giant wasps find a reason to be useful or still continue to embody unnecessary assholism?”

“Every organism has a purpose, even if it’s hard for us to recognize that. Many people look at wasps and think, ‘Those bastards sting people and don’t even produce honey! What a useless trash creature!’” he says, and I nod in agreement. “The reality of the situation is that there are many different types of wasps with many different lifestyles,” the last word I never thought I’d hear associated with insects, but he makes a compelling argument to think twice before condemning them.

“I wouldn’t hold my breath on that one, doc.”

Of course, he then says, “Here’s a fun example, because people generally hate spiders more than they hate insects. Spider wasps (family Pompilidae) sting spiders to immobilize them and drag them into a burrow where they lay an egg on it. The larva will eventually hatch, burrow through the spider’s exoskeleton, and feed on the insides until it is ready to pupate and emerge as an adult. I would like to also note that the spider is alive for this whole process.” His almost uncomfortable excitement doesn’t slow him down, “It’s not dead from that first sting, but merely paralyzed, and the larva saves the most important organs for the end! If that’s not badass, I don’t know what is,” he says, confirming that nature truly is quite scary.

“Other types of wasps simply feed on nectar or fruit, and certain ones are also recognized as efficient predators which can control pest insects. Generally, when people talk about wasps being assholes, they are referring to yellowjackets or other members of the family Vespidae.” Well, at least it is a family affair when they sting me, I think. “Yellow jackets are way more trigger-happy on stinging people when they’re agitated when compared to honeybees, and this is because of the structure of the stinger itself. Honeybees have strongly barbed stingers, which become lodged in the skin of mammals when they sting them. When the bee flies away after this, the stinger actually rips out of the abdomen along with some of the internal organs, causing the bee to die.” He’s trying to make me feel bad for them! “As a result, they don’t usually sting unless they absolutely have to. Wasps, on the other hand, generally have much smoother stingers, which means they can usually attack multiple times and not suffer any sort of repercussion, aside from maybe getting smacked!” Insect favoritism, I think.

“So the movie Ticks is bad, but it always made me wonder how big a tick could actually grow to be?” I ask. “The film says that ticks are the vampires of the insect world, is that accurate?”

“Ticks are most certainly not the vampires of the insect world, because ticks simply aren’t insects. They’re arachnids, alongside spiders, scorpions and mites,” he says, destroying another one of my good, carefully planned questions.

“Have you been unfortunate enough to see Red Planet?” I ask. “I did wonder what ‘nematodes’ were. The plot about the algae and the insects, and bugs that could create oxygen, how crazy is that?”

He hasn’t seen the film in a long time, but of course he knows about nematodes. “Nematodes are extremely small worms, which have the common name of roundworms. They are found nearly everywhere, and are incredibly small and thin for the most part, usually acting as parasites on or in various animals, humans included.” I sense another disgusting fact is around the corner, and he doesn’t disappoint. “As a scrumptious example, pinworms, which can infect people, live in their digestive systems, and come out of their assholes at night are a type of nematode!”

He pauses, attempting to recall the plot. “The algae was transported to Mars from Earth, and then the insects, which had been lying dormant on that planet for fucking eons, fed on that algae and produced oxygen as a byproduct. This seems pretty backward, since it’s plant life that produces oxygen on Earth! The insects could instead consume the algae and whatever else, producing carbon dioxide as a byproduct of both feeding and breathing.” I tried not to nod off, but that was more the fault of the film’s than his. “And then the algae could convert that carbon dioxide into oxygen. That would’ve made a lot more sense in my opinion, but there are probably details I’m forgetting! Should I watch it again?”

“No, and we should wrap this up.”

* * *

We talk for another hour as he moves on to reciting facts about animals that are not, in fact, bugs. However, I do want to thank BugDoctorr for this interview. He can be found on Twitter, where I am sure he’d love to lecture anyone about his insects. Next time you see a sci-fi movie with insects in it that brings up an interesting scientific question, maybe just don’t ask?