The Stiff Brown Cloth in Which the Knife is Kept

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #111. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Revisiting stories, old and new.

———

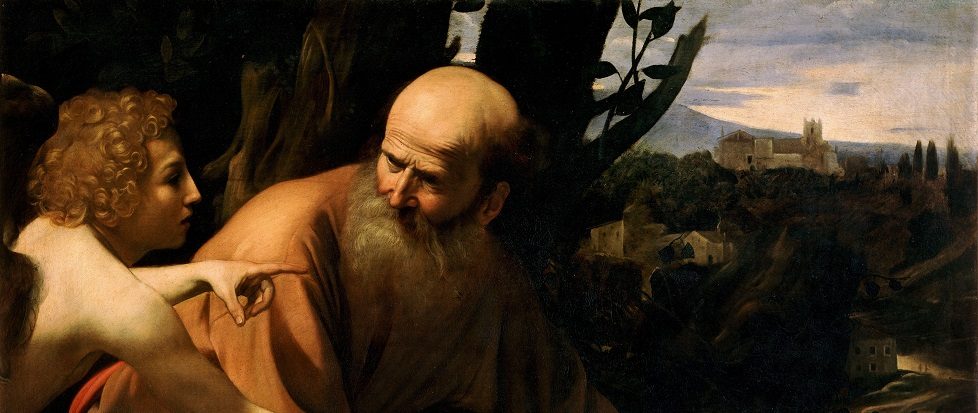

When I was a child, I learned the story of Abraham and Isaac.

In Genesis, Abraham takes his son Isaac up a mountain to kill him and burn his body as an offering to God. Isaac, without knowing it, carries the wood for his own funeral pyre.[

“Behold the fire and the wood,” Isaac says when they reach the top of the mountain, “but where is the lamb for the burnt offering?”

“God will provide,” Abraham says.

It is necessary to fill in a number of details. At school, I was reminded that Abraham was more than a century old. Isaac himself was a miracle, named after ancient Sarah’s disbelieving laughter when an angel told her that she would finally, finally have a son. There are other details.

A kosher slaughter involves severing the major structures of the neck with a single incision. There are strict standards as to the sharpness of the knife, which is to be inspected both before and after the slaughter, as well as the exact location of the incision—through the trachea but not the larynx so as to avoid impacting hard structures in the neck which could blunt the knife and impede the incision. If there is more than a single motion necessary to complete the slaughter, the animal is rendered inedible. A kosher slaughter results in a sudden and severe loss of blood pressure and near-instantaneous unconsciousness. The animal, however, must be awake and alert at the moment of the incision. Stunning the animal before killing it renders it inedible, ritually impure.

Tradition dictates that the standards for kosher slaughter were given to Moses on Mount Sinai, centuries after Abraham died. Even so, Abraham circumcised himself a full year before Isaac was born, so it’s safe to assume that he was handy with a knife.

Abraham binds Isaac when they reach the top of the mountain. We’re not told if Isaac fights or submits. There are no sweet promises to keep him docile. There is no moment of doubt where the younger man threatens to overpower his father and escape. It simply happens. Abraham ties up his only son to open his veins and bleed him to death. We’re not told if Abraham, ignorant of kosher law, hits his son in the head with a rock, or if Isaac watches with his eyes wide open as his father lifts the knife above his head.

A good storyteller would stretch this moment, and it would be different every time, but always exactly right. Isaac would struggle against his bonds, the handiwork of a conflicted old man, and he would almost free himself before feeling the hand of God Himself press him down against the cold, weather-worn pile of stones. The weight on his chest would be suffocating, and Isaac would know the unendurable presence of God. Abraham would fumble as he unwraps his knife from the stiff brown cloth in which it is kept. Abraham stops for an instant, frozen by the sight of his own blood, the same blood that runs through his son’s veins. This would be the moment that Isaac’s death becomes real to Abraham, the moment that it is a certainty, and in that moment, in the way that it has already happened, Abraham would finally be able to do it. Abraham walks to the altar without hesitation. He has done this before. He touches the knife to his son’s throat. Isaac does not protest.

Of course, we’re not told any of this. Abraham reaches out his hand to pick up the knife. That’s all. God speaks, and it’s over.

No, that’s not right either. God doesn’t speak.

“The angel of the LORD called unto him out of heaven, and said Abraham, Abraham: and he said, Here am I.”

It isn’t God. It’s an angel who can’t bear the sight of a man ready to kill his child. It’s the angel who lies to Abraham, “Lay not thine hand upon the lad, neither do thou any thing unto him: for now I know that thou fearest God, seeing thou hast not withheld thy son, thine only son from me.” It’s an angel in this story who prevents a father from murdering his child.

And God doesn’t notice. He isn’t paying attention.

But maybe it was different. Maybe Abraham wept, as Jesus did, even though he knew what was going to happen. Maybe he put a blindfold over his son’s eyes and told him a different lie. It was a magic trick, you see. God would provide the lamb, but it wouldn’t work if you were looking. Maybe the angel whispered in Abraham’s ear, and Isaac never knew anything at all. Maybe he cried with delight when Abraham tore off the blindfold to reveal the ram caught by his horns in a bush. It wasn’t there before, Isaac was sure of it. We don’t know how old Isaac is. He is never physically described.

We are never told the color of the ram.

It is worth noting that Isaac is not Abraham’s only son. Abraham has Ishmael, through Hagar, his Egyptian slave. He will eventually have five more sons from his second wife, Keturah. Isaac is Sarah’s only son. The angel is talking to her.

I was never taught any of this as a child, or even later. I was taught this story as a fable, a story in which the first thing you learn and the only thing that matters is the end. I was never asked to imagine what it was like to carry the fuel for my own cremation.

It is already over. We already know the end.

Except that endings are things of fiction and fable, and we are still piling the wood. Not to worry. There are other daughters, and there are always other sons.

———

Gavin Craig is a writer and critic who lives outside of Washington, D.C.