If the Devil Is to Exist in This World, It Cannot Look Like a Devil

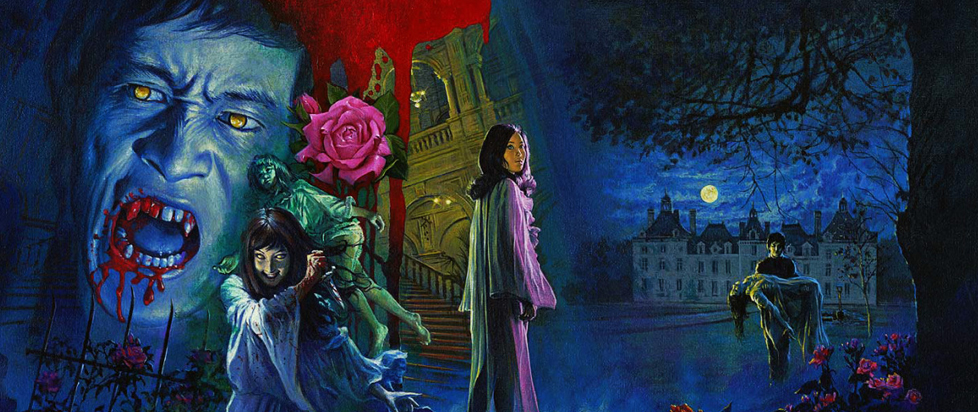

I’ve said before that nothing could be more on-brand for me, personally, than a trio of Toho movies aping Hammer movies. After all, Hammer’s line of gothic chillers is probably my favorite category of films, full stop, and many of Japan’s forays into the horror genre are not far behind. But implying that these movies are merely imitating Hammer is also unnecessarily reductive. As the booklet insert that comes with the Arrow Video Blu-ray eloquently points out, while the Hammer horror films may be the most obvious inspiration acting on the so-called “Bloodthirsty Trilogy,” these films are best understood by placing them within their own cultural and historical context, as well.

I’ve said before that nothing could be more on-brand for me, personally, than a trio of Toho movies aping Hammer movies. After all, Hammer’s line of gothic chillers is probably my favorite category of films, full stop, and many of Japan’s forays into the horror genre are not far behind. But implying that these movies are merely imitating Hammer is also unnecessarily reductive. As the booklet insert that comes with the Arrow Video Blu-ray eloquently points out, while the Hammer horror films may be the most obvious inspiration acting on the so-called “Bloodthirsty Trilogy,” these films are best understood by placing them within their own cultural and historical context, as well.

Of course, we already knew that, right? That’s a big part of the appeal. If these were just Hammer movies recast with Japanese actors, that wouldn’t be nearly as much fun as movies that actually bridge a couple of different horror traditions. Matango is one of my favorite movies for a reason: because there are rubber suit mushroom people in it. But, if that weren’t reason enough, it’s also a phenomenal adaptation of William Hope Hodgson’s “The Voice in the Night” and inescapably an Ishiro Honda film, made on the heels of King Kong vs. Godzilla and released right in the midst of Toho’s Showa-era kaiju flicks.

I first heard about the “Bloodthirsty Trilogy” – specifically Lake of Dracula, the second film in the unofficial set – several years ago, possibly from Kenneth Hite, who was working on The Thrill of Dracula at the time. But I didn’t get to actually see any of these movies in any form until Arrow Home Video released an amazing Blu-ray set of the whole trilogy. Which means that I got to enjoy the somewhat disappointing experience of watching the films in order, working my way from what is, without a doubt, the most inspired and possibly best of the three (The Vampire Doll) to the one that most resembles that reductive log line of Toho simply aping Hammer (Evil of Dracula). (Your mileage may vary, of course, and over at Birth. Movies. Death Jacob Knight calls Evil of Dracula the best “or, at the very least, the most purely entertaining” of the three films.)

One thing to understand is that the “Bloodthirsty Trilogy” isn’t really a trilogy. Triptych is probably a more honest description. No plot elements, characters or settings carry over from one film to the next, though they all share a director (Michio Yamamoto), screenwriter (Ei Ogawa) and composer (Riichiro Manabe), who help to give them a sense of unity, even while their story lines diverge pretty drastically.

One thing to understand is that the “Bloodthirsty Trilogy” isn’t really a trilogy. Triptych is probably a more honest description. No plot elements, characters or settings carry over from one film to the next, though they all share a director (Michio Yamamoto), screenwriter (Ei Ogawa) and composer (Riichiro Manabe), who help to give them a sense of unity, even while their story lines diverge pretty drastically.

Now might be a good time to talk about Riichiro Manabe’s scores for the three films, which I have seen described elsewhere as “often maligned,” but which were, for me, one of the most effective and memorable parts of an almost universally effective and memorable set of movies. Of the three, Lake of Dracula may have the best score, with suspense sequences that are accompanied by a weird and dissonant noodling on instruments that really shouldn’t work but does anyway. By Evil of Dracula, the incidental music has turned to jazzy riffing reminiscent of Manos, the Hands of Fate, while scenes of tension are backed by screeching static and Theramin.

The Vampire Doll, released in 1970, should have represented the director and the studio still getting their feet under them in this new European gothic vein, but instead it is perhaps the strongest film of the bunch, thanks in part to its tight running time, atmospheric direction, and genuinely unsettling ending, which brings in elements of Poe and reveals a capacity for human evil as bottomless as anything that Dracula himself could ever bring to bear.

Even as it opens in suitably gothic fashion, with a young man being driven through the rain to meet his girlfriend at her distinctly Western-style family manor out in the middle of nowhere – only to find, upon arrival, that she has met an untimely end – The Vampire Doll is already distinguishing itself from its Hammer predecessors, in no small part by being set in the present day, rather than some costumed past.

Not that the past doesn’t hang heavy over The Vampire Doll. In true gothic fashion, the return of the repressed is very evident in the story here, as a terrible crime which befell the household years ago still informs the strange and sinister goings-on within its walls. This early installment “feels Japanese” in ways that the other two gradually move away from and, both aesthetically and narratively, I was reminded as much of the horror manga of Kazuo Umezu as I was the Eurohorror of Hammer or its imitators.

Sure, there are old dark houses, dramatic lightning bolts, late-night disinterments, strange sounds coming from the off-limits basement and even a few bats, but there is also the wind whispering through tall grasses and the film’s “vampire,” with her long black hair falling around her downturned face, prefiguring the soggy ghosts who would haunt J-horror screens in decades to come.

Sure, there are old dark houses, dramatic lightning bolts, late-night disinterments, strange sounds coming from the off-limits basement and even a few bats, but there is also the wind whispering through tall grasses and the film’s “vampire,” with her long black hair falling around her downturned face, prefiguring the soggy ghosts who would haunt J-horror screens in decades to come.

(It bears mentioning that the word “vampire,” when used to describe these movies, is fraught with some translational complexities. These are explored with greater care than I could ever manage in the liner notes, written by Jasper Sharp. But nowhere is the term more of a potential misnomer than in The Vampire Doll, where the titular “vampire” lacks the traditional fangs, instead killing with a knife.)

Yukiko Kobayashi, who was in Yog Monster from Space (AKA Space Amoeba) that same year, plays the vampire here and she does so about as eerily as any vampire to ever creep across the screen, her smile every bit as haunting as the golden contacts which help her stand out from her European counterparts. A comparison has been made elsewhere between the look of her character and the “Blind Girl” photograph by Christer Stromholm, showing a Japanese girl who was blinded and scarred when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

Whatever their ultimate purpose, the golden eyes are a striking motif, and one of the only ones that repeats between movies, showing up again in Lake of Dracula, which takes the stylistic touches of The Vampire Doll and adjusts them one notch closer to the gothic chillers from which these movies are taking their cue. The vampires in Lake of Dracula share those golden eyes, but they also have the fangs that we’re used to seeing. Screenwriter Ei Ogawa is joined by Masaru Takesue on both this film and the next one, which may help explain why they feel more of a piece with their Eurohorror counterparts.

According to Toho’s international marketing department, “even vampires, when not at work sucking blood, probably enjoy sexual activity,” leading them to “doubtless foster offspring, albeit illegitimate ones. Dracula himself would have been no exception. It was thus during the early years of this century that one of Dracula’s bastard sons made his way to Japan, liked it and settled down.” However, none of the movies ever actually use the D-word in their original Japanese incarnations.

In the English version of Lake of Dracula, Shin Kishida’s character is simply credited as “the vampire,” but his physicality in the role is obviously influenced by Christopher Lee’s performances in the Hammer films and when the character perishes, he does so in a way that is clearly influenced by Lee’s iconic death scene in the first Hammer Dracula.

In the English version of Lake of Dracula, Shin Kishida’s character is simply credited as “the vampire,” but his physicality in the role is obviously influenced by Christopher Lee’s performances in the Hammer films and when the character perishes, he does so in a way that is clearly influenced by Lee’s iconic death scene in the first Hammer Dracula.

Shin Kishida is also one of the few familiar faces to show back up under pancake makeup in Evil of Dracula some three years later, though by then he has lost those iconic golden eyes and is used, unfortunately, to worse effect. Much of his silent physicality is missing, though he remains suitably sinister and suave during scenes when he isn’t done up in corpse paint with his mouth jammed full of vampire teeth. While the plot is a fairly clever bit of “vampire in a girls dormitory” shenanigans, Evil of Dracula was, for me, the low point in the triptych, even while it is also the movie that feels most like a direct lift of, if not the Hammer films themselves, then any of their various European mimics.

Bringing in an origin story for its “Dracula” that involves a Christian missionary shipwrecked in Japan and forced to renounce his faith and spit on the cross – not to mention some great imagery including a giant, unburied coffin – Evil of Dracula still isn’t content to rest entirely on European vampire tropes. During a particularly lurid third-act ritual, Evil of Dracula abruptly introduces an odd twist on the methodology of the vampires that not only makes them stand out from the crowd but also manages to visually call back to The Vampire Doll.

At the end of the day, it probably doesn’t really matter much whether the films of “Bloodthirsty Trilogy” are good or not. They are interesting, which, for fans of these kinds of obscure horror oddities, is more important. The fact that they are also mostly good – from the taut and effective The Vampire Doll through the lyrical Lake of Dracula to the occasionally shaggy Evil of Dracula – is just an added bonus.

———

Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, amateur film scholar and monster expert who was born on the night before Halloween. His stories of monsters, ghosts and sometimes the ghosts of monsters have been published in dozens of anthologies, including The Best Horror of the Year, and he is the author of the collections Never Bet the Devil & Other Warnings and Painted Monsters & Other Strange Beasts, not to mention Monsters from the Vault, a nonfiction book collecting his essays on vintage horror films. You can find him online at orringrey.com