The Sand and the Sea

Gavin Craig has a lot of games on his shelf that he’s never played. Backlog is his attempt to correct that.

———

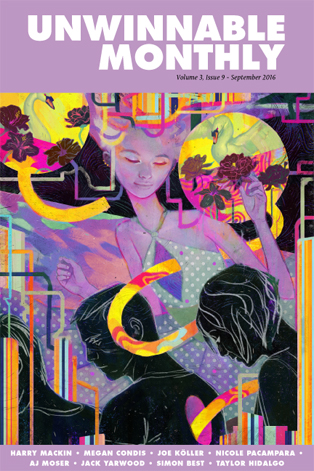

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #83, the Love issue. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Back in January, when I started writing about my backlog, I predicted that for all my efforts the list of games I intended to play but hadn’t gotten to yet would be longer at the end of the year than it was when I started. Nine months in, I can confirm that I was correct. I’ve been spending my time playing games from years past, which has left me deeply behind on playing games from this year.

Act IV of Kentucky Route Zero is waiting for me, in its magnificently peculiar unhurried fashion. Inside is finally out on PS4. I need to make time for That Dragon, Cancer and Hyper Light Drifter before Quadrilateral Cowboy comes out for Mac in September. In all honesty, I’m probably not even going to bother with Overwatch, Uncharted 4 or No Man’s Sky. It’s possible that I’ll go the whole year without buying a full-price $60 new release.

Falling behind is in fact the eternal condition of the media critic.

To make things worse, it’s even harder for me to keep up during the summer, as having the kids home during the day means that M-rated games are off-limits, and I can’t just spend all day holed up with my computer.

Even though it stretches the category of the backlog for a monthly column, this month I played Abzû, Giant Squid’s underwater exploration game, with my daughters watching the entire time. Giant Squid’s founder, Matt Nava, was art director for 2012’s Journey, and it’s clear that Abzû is an attempt to create a similar sort experiential parable. In Abzû, as in Journey, a lone survivor of a lost society navigates and rediscovers their world through the exploration of its ruins. In both games, cultures that started out aligned with nature turn their energies toward the creation of destructive technologies, a process reenacted through the player’s progression through the game world.

Abzû is every bit the visual marvel that Journey was and even more of a technical accomplishment, teeming as it is with marine life, painstakingly rendered and simulated in an active ecological context. There are stone shark heads distributed throughout the game, upon which the player can direct their avatar to “meditate” and identify the species in their immediate surroundings, each of which behaves roughly as it does in the wild, congregating in schools or swimming alone, hunting and being eaten as the player watches.

My daughters could hardly contain themselves during a sequence when the player encounters a pod of blue whales. They named a mother whale “Bluey” and her baby “Ocean Song.” They also named a great white shark Rufus. Describing the course of their emotional investment in Rufus would involve significant spoilers, but suffice it to say that things happened and they had opinions on the matter.

As a fable, however, Abzû lacks something of Journey’s depth. I think a lot of this has to do with the strength of storytelling – as many elements as Abzû and Journey share in their setup and execution, Journey spends a lot more of its energy telling its story, while Abzû is a bit more archaeological. In Abzû each level brings the player to an area resembling a temple, with walls of azure tile and bas-relief figures depicting humanoid beings communing with the sea. In Journey, the player is immediately linked to the robed beings depicted in visions and glyphs. In Abzû this connection isn’t initially clear and, while the swimmer is eventually revealed as more than just a random explorer, there’s a sense of oneness that pervades Journey that is absent in Abzû.

In Abzû, nature and society are poles at odds with each other. A lost society created weapons and machines that destroyed its people. This technology remains to threaten the natural world. An avatar of nature is introduced as being hostile to the player, but eventually sacrifices itself attacking the machines and, through this avatar’s revival, the swimmer transcends the divisions between the natural and the technological. In Journey, there are no such divisions. Society and nature consist of the same substance, cloth animated by luminescent energy. Even when society’s conflicts and machinery threaten to destroy it, they remain linked to the natural world.

This results, even beyond differences in the ambition and depth of the storytelling, in a fundamental distinction between the roles performed by the player in the two games. In Abzû, the swimmer seeks to restore the world, liberating nature from the grip of annihilating technology. There are transcendental elements to the player’s task, but it’s much closer to a conventional positioning of the player as hero, saving the world, or at least providing an assist. Journey, on the other hand, is not asking the player to restore the world so much as reenact it, resulting in an almost ritual experience. The player is a pilgrim, on a journey that may be personally transformative, but whose purpose is to reanimate and reinvigorate rather than reshape the world.

This process – the enactment of a determined world – is what most games do, but it is not what most games ask you to tell yourself you are doing. The code that creates a game is the same when we are done playing as it was before we began. It may tell us stories of transformation and heroism, but we are the only element capable of being truly changed. We help set the world in motion, but it exceeds and escapes us.

Abzû doesn’t quite get there, but it makes a fine effort. If nothing else, it’s an outstanding virtual swim before the end of the summer.