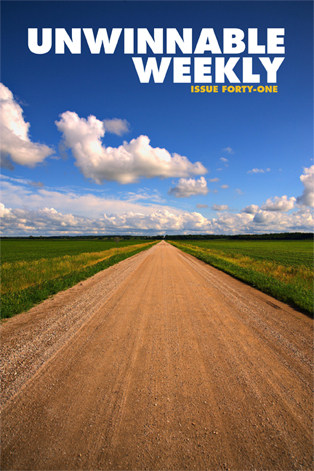

The Open Road

The following is a reprint from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Forty-One. If you enjoy what you read, please consider purchasing the issue or subscribing.

The following is a reprint from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Forty-One. If you enjoy what you read, please consider purchasing the issue or subscribing.

———

Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road,

Healthy, free, the world before me,

The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose.

Henceforth I ask not good-fortune, I myself am good-fortune,

Henceforth I whimper no more, postpone no more, need nothing,

Done with indoor complaints, libraries, querulous criticisms,

Strong and content I travel the open road.

– Walt Whitman, “Song of the Open Road”

The road from Escalera, Punta Orgullo. Dusk.

I am on a hill above Escalera, watching the sun set across Nuevo Paraiso. It’s 1911 in Red Dead Redemption’s version of Mexico and the Southwestern border states and the virtual people are disappearing into their polygonal clapboard houses for the evening. I direct my horse to a standstill overlooking the road, and watch as the world desaturates into night, everything in the east fading into streaks of blue and pink and grey. It isn’t necessary, but I’ve named my horse Thowra, after the silver brumby of Australian children’s stories that I loved when I was a little girl.

Thowra and I – that is, John Marston – have begun a journey across the landscape in search of the sun. I figure I can see a sunrise or a sunset every 50 minutes or so, which is about how long it takes for a day to pass in-game, and I want to be at a different lookout each morning and night. I feel like the Little Prince of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s classic tale, perpetually shifting my chair to see the next solar spectacle from my planet.

Thowra and I – that is, John Marston – have begun a journey across the landscape in search of the sun. I figure I can see a sunrise or a sunset every 50 minutes or so, which is about how long it takes for a day to pass in-game, and I want to be at a different lookout each morning and night. I feel like the Little Prince of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s classic tale, perpetually shifting my chair to see the next solar spectacle from my planet.

Or the wanderer of Walt Whitman’s great poem. It’s been a long time since I’ve had the means and opportunity to travel in real life and wandering on horseback through the wild, simulated world of a Western seems a decent alternative. I also live in a city, and sometimes you just want to see a sun at the horizon without buildings and aerial towers in the way. And so, here I am, on a hill above Escalera.

The first time I noticed the sunrise in this game I was learning to capture wild horses at MacFarlane Ranch. The sun stretched its light arms over the plain; I rode Thowra in circles as I admired the painted gold of dawn, the shimmer of pixels through jagged tree branches, the orchestra of sampled birds, horses, and wind.

Nuevo Paraiso to Cholla Springs, New Austin. Midnight.

The sands of Punta Orgullo are white. Wikipedia tells me that this valley – the real valley that perhaps inspired it – was once at the bottom of a shallow sea, and over 100 million years of geological activity has risen to create the basin here. The sand is white because it is made of gypsum. Gypsum sand is rare: in most places the mineral dissolves in water, but the aridity of this area has allowed it to form white dunes, crisscrossed now by paths and wagons.

Elsewhere in Nuevo Paraiso, the mesas – towering, red, scraped flat – are similarly the result of slow, geologic processes. Through weathering and erosion, layers of sediment have built, strata by strata, castles in the desert. These are the monoliths that lead me to forget I was going to make a cup of tea, and how much time has passed since I picked up the controller.

Elsewhere in Nuevo Paraiso, the mesas – towering, red, scraped flat – are similarly the result of slow, geologic processes. Through weathering and erosion, layers of sediment have built, strata by strata, castles in the desert. These are the monoliths that lead me to forget I was going to make a cup of tea, and how much time has passed since I picked up the controller.

It’s a cyborgian process. My left thumb is pressed to a swivelling stick and my right alternates between a button and another stick. I mash the button to outrun a pack of coyotes that wants Thowra for dinner; I swivel the right stick to get a better view of the path disappearing behind me and the armadillo waddling to the side as I ride past.

The controller has become a part of me, an extension of my body through which I traverse the landscape in the screen. It is a channelling device for reaching and interacting with other worlds; a conduit of places and environments and stories. Trees and mountains pop into view, and in the distance, the plains of Cholla Springs emerge from the digital ether. This is where the game began, in cutscenes of a train journey to Armadillo, John Marston being blackmailed by government agents.

Marston is an ex-outlaw whose family is held hostage by the government. He must track down his former comrades across the closing frontier in order to save his wife and child. I am not impressed by the story, but that doesn’t mean I can’t play with the stage and sets built for it. There are stories, too, in every controller and every pair of hands enclosing them, and these are the stories I think about while I quest toward Armadillo.

Marston is an ex-outlaw whose family is held hostage by the government. He must track down his former comrades across the closing frontier in order to save his wife and child. I am not impressed by the story, but that doesn’t mean I can’t play with the stage and sets built for it. There are stories, too, in every controller and every pair of hands enclosing them, and these are the stories I think about while I quest toward Armadillo.

It is nearly morning. The land has changed: it is more brown than red and the white sand is gone. I hear, distantly, the bellow of an oncoming thunderstorm.

Armadillo, Cholla Springs. Dawn.

Thowra is hitched outside the saloon in Armadillo and I’ve walked into the plain as dawn approaches. I want a clear view of the sun rising but its too late in the morning to ride in search of an elevated lookout. John Marston is outlined against the fading light, his silhouette idling amongst the scrub as I angle the camera upwards for a better view of the sky. It’s a shame there’s no first-person perspective. I watch the sun fall over his shoulder; if I squint I can almost pretend it’s her shoulder.

The open-world promise of this game brings me, again, to Walt Whitman’s poem. Written in 1856 – 15 years before Marston arrives in Armadillo – it goes like this:

The open-world promise of this game brings me, again, to Walt Whitman’s poem. Written in 1856 – 15 years before Marston arrives in Armadillo – it goes like this:

Allons! the road is before us.

It is safe – I have tried it –

my own feet have tried it well –

be not detain’d!

It could be the siren song of every game of this type, with all their free-roaming boasts and caprices. I’ve read it many times before: here, you can go anywhere. Do anything. There are mini-games and side stories to pursue. The whole world is yours to explore, for better or worse. All of this in Red Dead Redemption is experienced through the life and story of John Marston.

———

In the beginning, I didn’t mind that this was a story about a man named John Marston, but the longer I’ve played the more alienating the experience has become. TransMovement: Freedom and Constraint in Queer and Open World Games explores further. Allen writes, the “supreme motility of the open-world game…often functions as an exaggeration of the freedom of cisgender men.”

I can’t help but think about this as I watch Marston idling in darkness being washed away by waves of sunlight. I am envious of the freedom and the space, both in gameplay and narrative, that this character embodies. He is a powerful figure, confident in his ability to counter violence, reckless because he can afford to be and glorified in the way only anti-heroic leading men often are. He goes wherever he wants and what violence he experiences is never because he is a man; it is because he was once an outlaw (or because someone wants to steal his horse).

And so: like most Westerns and open-world games, the sublime world beckons and the man walks through it. Female characters are rarely, if ever, given the freedom to explore these places as male characters are. A cursory glance of media reveals there are few epics of women venturing far and alone throughout wilderness, under sun and moon, in quests of their own.

Why such stories about women remain untold in the medium of so-called escapist fantasy, I don’t know, but I know that the real world is full of constrictions and unspoken rules on where I can safely go and how I ought to behave. Don’t go there, at that time, wearing that, watch out – always – for you may bring ill upon yourself.

Game worlds beckon as alternatives to a fettered state of mind. I yearn for a uniquely female experience of time, place and journey. Each game world has the potential for hundreds of stories – if the creators want it to be so. That the same kind of human is the protagonist over and over again is not a testament to the universality of white, straight men’s stories and interests, but an omission of all the diversities of humanity. Give me another Aveline de Grandpré, another Kat. Give me their successors (in flagship games, on consoles people actually play) and scatter them across boundless worlds. Grant them the glory and freedom their male counterparts have taken for granted.

And so: I squint at the sunrise and pretend for a few minutes that I’m looking over the shoulder of Jane Marston. And I remember something Sylvia Plath wrote in her diaries:

My consuming desire is to mingle with road crews, sailors and soldiers, barroom

regulars – to be a part of a scene, anonymous, listening, recording – all this is

spoiled by the fact that I am a girl, a female always supposedly in danger of assault and battery…I want to be able to sleep in an open field, to travel west, to walk freely at night…

The song of the open road was not written for us.

———

The woods of West Elizabeth. Evening.

We enter West Elizabeth via Dixon Crossing. It is dusk, and a flock of birds, or bats – I can’t really tell – shrieks through the trees as I ride by. It seems a bad omen. The road muddies among forest and snow as I push Marston towards the “civilized” town of Blackwater. This is Marston’s mile end, and with it comes the automobile, ladies in clean dresses and paved streets that clatter, unwelcoming, under Thowra’s hooves. It’s the usual closing-of-the-frontier theme. The game will end soon, and the dust of the open road will be packed under the cement of city sprawl.

We enter West Elizabeth via Dixon Crossing. It is dusk, and a flock of birds, or bats – I can’t really tell – shrieks through the trees as I ride by. It seems a bad omen. The road muddies among forest and snow as I push Marston towards the “civilized” town of Blackwater. This is Marston’s mile end, and with it comes the automobile, ladies in clean dresses and paved streets that clatter, unwelcoming, under Thowra’s hooves. It’s the usual closing-of-the-frontier theme. The game will end soon, and the dust of the open road will be packed under the cement of city sprawl.

Already I have had enough of the sun. I’ve bought a cabin on the outskirts of Manzanita Post, a station close to the forest and the last wilderness before Blackwater. At this point I have a lot of photos of my television screen on my phone. Night has come to West Elizabeth and I venture away from the cabin, into the forest. I look for constellations in the sky, wondering if the people who drew the texture that stretches over the game’s world captured the likeness of the stars in the northern hemisphere. (They didn’t.).

———

I said in the beginning that I had not traveled in a long time. This is no longer true. Since I began this written expedition, I have been to Scotland, to the Isle of Skye, where the Black Cuillins cut igneous chunks out of the horizon. I have walked alone on a path through the moor and felt kind of fearless, so long as it was just me and the heather and the mountains and the sky. I feel the same stirring now – curled in front of my TV, eyes caught on plasma – as I did then. Let these journeys change me. The polygonal and the corporeal. Let me experience them through a kaleidoscope of characters and stories, because these are big worlds and I feel there must be more to tell of them. It is not always open, but the road is always there.

———

Stephanie Vidot is a writer and radio producer from Brisbane, Australia. You can find her on Twitter at @crushthelily.