The Three-Dimensional Paragraph

A few years ago, a colleague of mine, desperate to express frustration with a particular student, said something along the lines of, “He can quit reading literature and go back to his comic books.” As a fan of comics, I was crushed. She equated a bad student with a whole genre of literature for which I felt an extreme affinity. I wanted to throw some witty remark back, something biting and at the same time celebratory about the genre. Instead, I laughed and walked out of her room. But it got me thinking about using comics in the classroom.

A while later, I approached my department head about creating a class that would deal specifically in comic books. She shut me down. I didn’t get much of a reason, but I assumed it was due to the preconceived notion of what a comic book is and for what it stands. So I set about changing the perception of comic books.

[pullquote]I am trying to break down barriers of perception about what comics stand for[/pullquote]

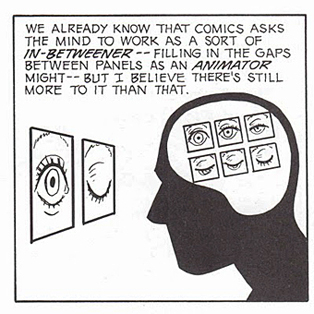

I studied literature that supported using comics in classrooms to help struggling readers. I came across a plethora of material that said comics were a great way to help poor readers become better. The reason? Comics involve a process of reading known as “inferencing,” a higher level of ability that forces the reader to make cognitive leaps in the spaces between each panel.

In Understanding Comics, a brilliant treatise on the genre, author Scott McCloud calls that space between panels “the gutter.” To further elucidate, McCloud writes, “Here in the limbo of the gutter, human imagination takes two separate images and transforms them into a single idea.” While a student may not be able to understand the paradoxical opening of Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, he will most likely be able to connect movement across two sequential images placed side-by-side. Hell, even cavemen understood this.

Will Eisner explored similar themes in his book Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative. Eisner points out that cavemen are truly the earliest comic book artists. They used a series of images to depict a particularly memorable event, like a hunt for example. Even readers today can understand how a caveman hunted buffalo. So if the caveman could understand the idea of graphic storytelling, who’s to say a high school student couldn’t also use the same inductive reasoning?

Furthermore, comics aren’t just for kids. Many serious writers have explored comics as a medium for storytelling. In bashing comics, my colleague neglected classics such as Maus, Persepolis, Pride of Baghdad and the apex of graphic novels, Watchmen. Epics such as The Odyssey and The Iliad have been adapted for comic audiences, and where the writer of a novel has as much space as he desires to tell his tale, the writer of a comic has to appeal to the visual and narrative senses of his reader.

Furthermore, comics aren’t just for kids. Many serious writers have explored comics as a medium for storytelling. In bashing comics, my colleague neglected classics such as Maus, Persepolis, Pride of Baghdad and the apex of graphic novels, Watchmen. Epics such as The Odyssey and The Iliad have been adapted for comic audiences, and where the writer of a novel has as much space as he desires to tell his tale, the writer of a comic has to appeal to the visual and narrative senses of his reader.

I didn’t truly feel vindicated until I read the essay “Superman and Me” by Native American author Sherman Alexie. Alexie wrote his essay about learning to read through Superman comics. He explains the process, saying:

Each panel, complete with picture, dialogue and narrative was a three-dimensional paragraph. In one panel, Superman breaks through the door [. . .] I look at the narrative above the picture. I cannot read the words, but I assume it tells me that ‘Superman is breaking down the door.’ [. . .] Because he is breaking down the door, I assume he says, ‘I am breaking down the door.’ Once again, I pretend to read the words and say aloud, ‘I am breaking down the door.’ In this way, I learned to read.

At times, I imagine that I am a lot like Superman in the Alexie essay. I am trying to break down barriers of perception about what comics stand for. I am trying to get people to realize that the space between the panels – the gutters – is where true learning takes place. A student may never pick up a copy of The Odyssey and explore Homer’s original Greek language, but we should be asking ourselves, “Does he have to?”

I have an M.A. in Literature from the University of Maine, and I am as much a literature snob as the next master’s student, and I willfully push books on people all the time. But I also push comics. Why? Because comics allow readers a little leeway but still give them the option of adding their own flavor. I don’t know what Spider-Man really sounds like, but I hear his voice in my head when I read a Spider-Man comic. I’ve never been to Oa, but I hear the ever-present hum of the central battery terminal.

I have an M.A. in Literature from the University of Maine, and I am as much a literature snob as the next master’s student, and I willfully push books on people all the time. But I also push comics. Why? Because comics allow readers a little leeway but still give them the option of adding their own flavor. I don’t know what Spider-Man really sounds like, but I hear his voice in my head when I read a Spider-Man comic. I’ve never been to Oa, but I hear the ever-present hum of the central battery terminal.

In both cases, I am a willing participant in an imaginative connection. As McCloud writes, “Participation is a powerful force in any medium.” So why wouldn’t we want students actively participating in the transformation of information between writer and reader?

The person who stamps on this type of creativity is the person who shuts out a whole field of literature that offers as much as, if not more than, traditional literature. If we’re willing to close this door, then we’re willing to damn our students to a life of abject failure because we were too stuck in our ways to adapt to changes in learning.

We have to be willing to let students read comics. We have to be willing to shift focus from black words on white paper to a mixture of color and imagery, regardless of how we feel about its existence.

We have to be willing to let Superman knock the door down.

———

Follow Brian Bannen into the space between things on Twitter @Oaser.