Apocalyptic Pregnancy

This is a feature excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly #174. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

It snowed in Brooklyn this winter. I watched three-year-olds experiencing it for the first time in their lives. This worries me. I’m supposed to have a baby in July, and I don’t know how to introduce it to my city when there is still a dangerous and slippery virus circulating unchecked. More to worry about.

When I first started thinking about apocalyptic pregnancies a friend texted, “I know some people who are currently pregnant in an apocalypse.” Now I am.

“Apocalypse” suggests certainty; a point at which the end is nigh, if not here already. Similarly, birth brings with it a kind of finality that pregnancy does not have. With birth there is a life, no matter how short, and with apocalypse there is an end, no matter how long. Pregnancy, on the other hand, guarantees nothing. There is hope and horror in conception, just as there is now, as we wait to see if this is a chapter of dystopia from which we might imagine a way out, or the epilogue we call post-apocalypse.

Perhaps an emotional response to a presidential election year, the weather, uncontrolled rent, or genocide – people on a large scale are questioning parenting as an ethical choice. The New York Times framed it as a conundrum, “To Breed or not to Breed,” while The Cut took a firmer position, “Don’t Let Climate Anxiety Stop You From Having Kids.” This precarity – in the world and in our bodies – means that pregnancy is often framed as a symbol of hope, or freedom – a kind of counterweight to the terminable-ness of end-times. Writer and climate activist Andreas Malm is aware of this and when his interviewer suggests looking to his children for hope he responds: “Yes, but I have to admit to some kind of cognitive dissonance, because, rationally, when you think about children and their future, you have to be dismal.”

This dissonance is built on a large body of fiction about very important pregnancies in the apocalypse. Sometimes the babies that might result from these pregnancies are the literal salvation for humanity, and sometimes the hope that they represent is more symbolic. The “potential baby” as a symbol of hope and freedom is a potent one – I wrote as much to a friend in 2020 – but, as scholars like Lee Edelman have theorized in works like his 2004 book No Future, it is a symbol that shores up the same neoliberal ideologies that help make contemporary apocalypse feel so close.

Take the Battlestar Galactica’s (2004) season two episode, “The Captain’s Hand,” in which President Roslin – a pro-choice candidate prior to the human genocide at the hands of cyborgs – outlaws abortion amongst surviving humans with the rationale that continuing the human species is more important than reproductive rights in the face of a diminished population. Not a calculation that I agree with, but it is one we see in our world as conservatives sweatily try to coerce childbirth instead of creating pleasurable conditions for parenting. Ironic, then, that in Battlestar’s world both the plot and human species come to turn on a – desired – very important pregnancy that isn’t entirely human.

The desire I have for my current pregnancy has reasons ranging from the mundane – I think parenting will be new and interesting – to the social – ideas about family – to a more abstract, expressive suspicion that the love I share with my partner is replicating too quickly to be contained by only two bodies. This doesn’t stop me from judging a fictional character who has made the same decision. Sometimes it feels like we are supposed to.

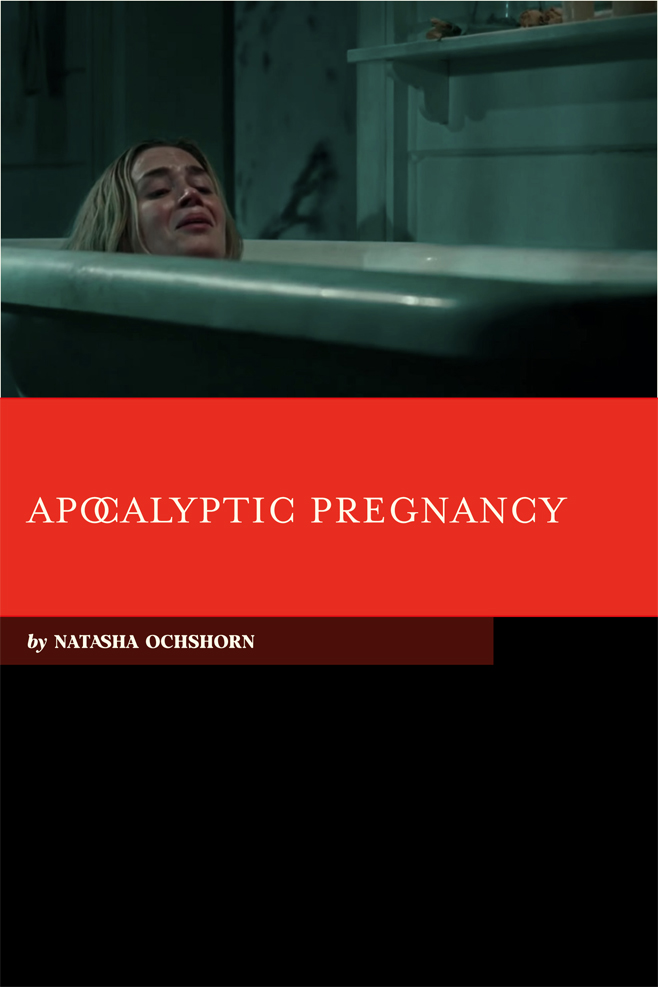

The swollen belly of Evelyn, the character played by Emily Blunt in John Krasinski’s 2018 film A Quiet Place, dares us. The abandoned world has been invaded by creatures with extra-heightened hearing who attack anything that makes noise. I first saw the film in a theater crowded with teenagers who gasped and laughed when we saw that belly. Babies, and their deliveries, are loud, unreasonable and full of complications even under the best circumstances.

The film clearly feels that it must answer for her choice. After the baby is born, removed for the first time in months from its weight in her body, Evelyn fixates on the weight of another child, killed by monsters in the first scene of the movie. “I could have carried him” she says a few times, as if wondering why she could carry this boy and not the other. She shifts abruptly, “Who are we . . . if we can’t protect them.” This is also repeated. Having symbolically performed the carrying that she failed to do for her other son, she is able to articulate this pregnancy as a fulfillment of purpose. This scene would be a clear thesis even if Krasinski didn’t affirm it repeatedly in press interviews. It reveals a dark wish at the center of the film; that end times could be freeing, clarifying even. That without the distractions of modernity we could re-focus the nuclear family; a deeply conservative desire echoed in the rhetoric of white supremacist doomsday preparers and ecofascists. Within this framework, Evelyn’s pregnancy becomes a symbolic reinvestment into these values. I preferred it as a comic jump scare.

These apocalypse narratives demand so much justification that it inevitably sidelines the pregnant person and their wishes. Children of Men, the 2006 film by Alfonso Cuarón is one of the worst offenders; a story about pregnancy that has very little interest in its pregnant character. Kee is a Black African refugee living in England and her pregnancy is very important, occurring in an infertile world. However, we learn very little of her feelings or desires as the film focuses instead on the white man, grieving the loss of his own child, who is tasked with her protection. Sidelining Kee’s interiority turns her into a symbolic vessel for a hopeful future, a salvo for male regrets, an endangered womb. This is not an acceptable response to a reproductive apocalypse. As we can currently see in America: it is the conditions of reproductive apocalypse.

———

Natasha Ochshorn is a PhD Candidate in English at CUNY, writing on fantasy texts and environmental grief. She’s lived in Brooklyn her whole life and makes music as Bunny Petite. Follow her Twitter, Instagram and Bluesky.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 174.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!