Ideology Speaks Through Architecture: Exploring Inside and Gorogoa

Space is perhaps represented most truthfully, and with the fewest barriers to expression, in videogames. Digital spaces are not bound by the limiting realities of real-world physics and scale, allowing for boundary-breaking architectural expressions that simply wouldn’t be reasonable or even possible to construct otherwise. When materials and time are not a question, the symbolic potential of spanning cosmic worlds is only limited by the imaginations of their dreaming creators. Two excellent examples of how games can embrace the limitless potential of digital architecture are Inside (2016, Playdead), and Gorogoa (2017, Jason Roberts). Whereas Inside demonstrates the depths of oppressive architectural language, Gorogoa does the opposite by elevating space beyond the physical into the cosmic.

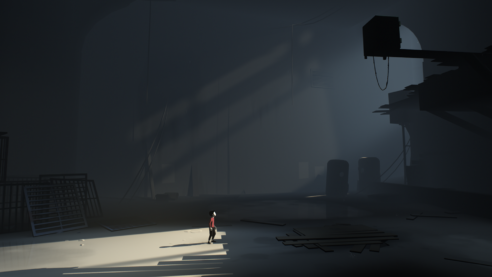

It’s clear that the reigning powers of Inside associate the sprawl of physical infrastructure with social domination. Why else would there be so many lonely hallways and sparse warehouses, their empty confines yawning far into the background? This can be seen during an early-game section where the boy escapes a vicious dog by latching themselves to a rail system. Here, the boy is pushed high along the ceilings of multiple vast concrete structures, housed only by the occasional lone barrel or stack of crates. It’s obvious that these rooms are deserted, or maybe were never used beyond the storage of arbitrary debris. These spaces, their cavernous nature matched only by their utter emptiness, can be found throughout the entire game, and it suggests that they serve no other purpose than to exist. Skyscrapers stand tall as watchful sirens and deserted blank streets carpet the ground like grass. In this dystopian world, it only matters that the harsh infrastructure stands tall and threatening, a sign of its master’s utter control, even if nothing further is accomplished by its being. The message is the function.

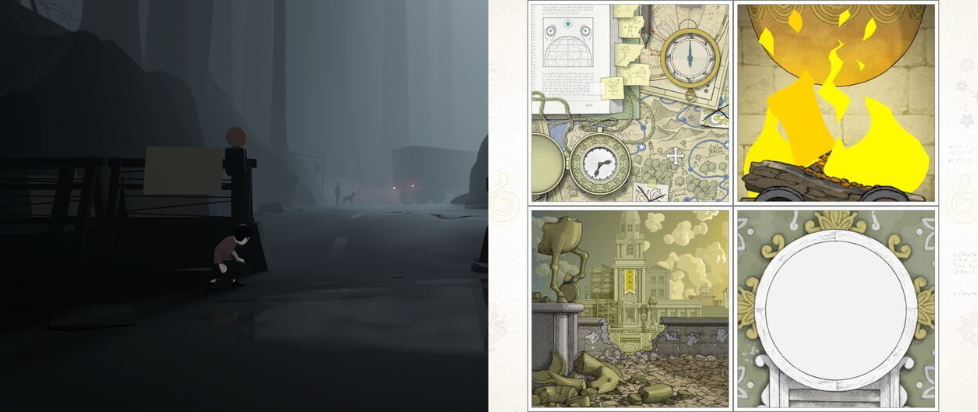

While Inside’s spaces may feel empty and cruel, Gorogoa’s are intimate and packed with transcendental meaning. Throughout the game, the player will dismantle and reassemble numerous frames in order to alter their purpose. Even something as seemingly small and arbitrary as a painting on the wall can become a portal to a new space through re-contextualization. Examples of this can be seen as early as the first chapter when the boy stands in a dim hallway closet. Initially, the closet door has one obvious use – as a barrier between the hall and the inner closet. But when the player stops viewing this door merely as a physical barrier and rather as a cosmic frame, something special occurs: the door gains a new axis of meaning, and can now transport the boy to another building across the street with a mere step forward. As said by the creator of Gorogoa, “Humble objects can be the intersection between two points of meaning… [It] allows the sacred, if you will, to be accessible through the mundane” (Roberts, “Gorogoa: The Design of a Cosmic Acrostic”). This approach, which Roberts defines as a “Cosmic Acrostic”, is interesting because it extracts lots of meaning out of very little physical space. Entire worlds are traversed within paintings and photographs, and significance is derived from even the simple power of the doorway.

Another noteworthy contrast between these two titles is the overall shape of their architecture. As noted in the essay “Poetics by Progress” by Gareth Damien Martin, “A map of Inside’s descent, shows how, despite the illusion of a return to the surface, the game’s structure, architecture and even its horizon line descends impossibly”. Though ostensibly taking place in a fully three-dimensional space, the boy traces a direct line right and ever down on a flat plane, creating a path reminiscent of a plunging graph. The boy travels from sunny rooftops to shadowed hallways to dim subterranean caverns, and even a pitch-black trench under a synthetic sea. Elevators are ridden and ladders are climbed in the meantime, but they act only as minor distractions from the constant descent. This occurs as early as the first few minutes of the game when the boy leaps into a shallow pond beneath a stone overhang. Despite immediately trudging out of the water and climbing upwards once again, they are soon met with a muddy hill that cascades their tumbling form even further down into the bank of an old field. Eventually, the boy is subsumed into the Huddle – a mass of writhing flesh that constitutes the heart of this awful world, and any sense of escape or ascension is permanently lost. While this may be a pitiable thing to watch in real time, it is hardly surprising in retrospect: This shape was being drawn from the very beginning, and the player was merely too close to see it.

Meanwhile, Gorogoa takes on a more inscrutable form. Despite its art style suggesting a world with only two vectors, it is quickly apparent that the game exists as a complex 3D shape that folds time and space back on itself, while always traveling upwards. This is seen in micro-scale during a late-game scene where the player arranges railroad tracks to form ladders, which the boy then climbs in order to reach the top of an important tower. The tracks did not originally exist on an up-down vector, and yet they were re-contextualized to achieve physical upward movement. Much of the game’s progress is marked in this type of ascension – such as the bird that flies away into the sky at the end of the first chapter, and the glinting stars that must be captured in the confines of grounded paper. These individual scenes mimic a narrative that follows a young boy through adulthood as he attempts to appease an obscure god and ultimately achieve transcendence. Despite his initial boyhood offering falling on deaf ears, the man is eventually accepted by his god at the end of the game with the same offering, suggesting that his life of study and obsession was not in vain, but rather a constant progression that he simply couldn’t see at the moment. In this way, the game takes the shape of a spiral staircase that is always stretching skyward, even if the climber feels like they are traveling in circles.

Inside and Gorogoa make excellent companion games precisely because they offer parallel methods for contriving meaning out of a game space. Inside takes place in a bitter dystopia where a faceless young boy in a red shirt struggles against the inevitable end, and the hollow architectural sprawl conveys that ideology without a single word. Gorogoa takes place at the center point of a spiritual crossroads where a faceless young boy in a red shirt becomes something more than they ever could have dreamed, and the flowing intimacy between each space reflects that. Inside sprints and slides ever-downward, while Gorogoa carefully climbs a spiral staircase. Through the thoughtful use of architectural symbolism and defining shapes, the languages of oppression and transcendence can be portrayed with equal weight and meaning.

———

Hayes is studying game design and technical art at the University of Utah. You can find more of his ramblings here.