Eat, Prey, Love

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #161. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Interfacing in the millennium.

———

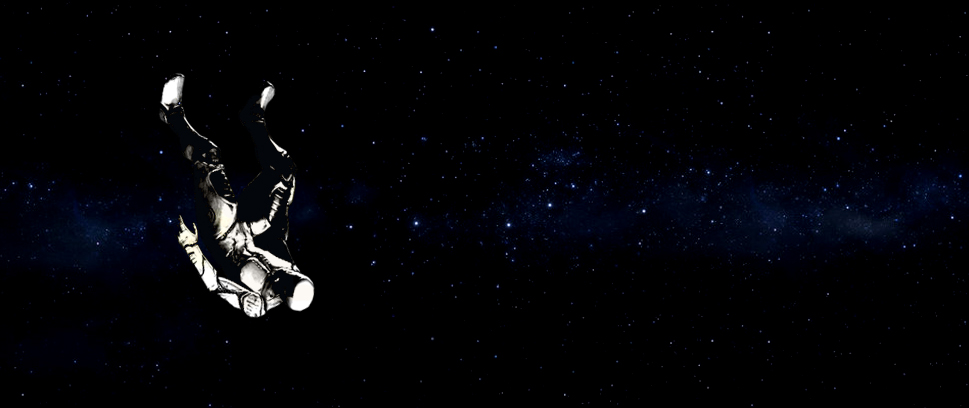

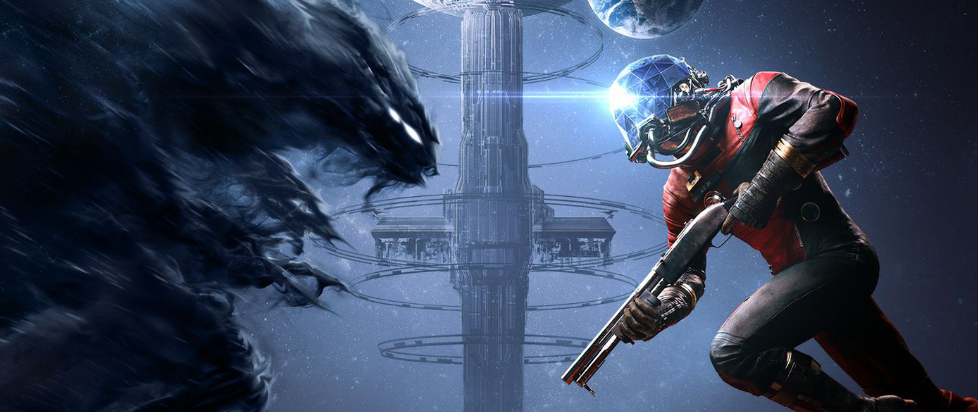

By the time the player gains control of the protagonist of Prey (2017), Morgan Yu, Talos I has already been irrevocably changed. The physical evidence of alien infiltration is everywhere: beyond half-open doors, on the walls, in the air. The space station has been cracked open like a lock and laid out for show; the Typhon float through it, barely concerned with any physical barrier, and the human crew hide like rats.

It’s a sharp contrast with Arkane Studio’s earlier work. In the Dishonored series, the protagonists were the rats, often literally – Corvo, Daud, Emily and Billie ghosted across the landscapes of Dunwall and Karnaca and left only shadows in their wake. If they were particularly bloody-minded, they could influence surges of violence, plague and physical darkness brought about by a narratively-relevant change in the weather, but you’d never find their actual bodies leaving as much as a fingerprint. Prey is the opposite. Morgan’s trademark weapon is the GLOO gun, the game’s favored gimmick, which spits popcorn-like handholds across any static surface in the game; the recycler charges that the game encourages you to throw chew up not only enemies but scenery, reducing them to their component parts and leaving carefully-designed interiors looking like empty sets. The Typhon enemies are flamboyantly organic excess, content not only to roam the levels but to expand within them, testing always for the weak spots of the cage that contains them, whether that’s through the effervescent, harmless coral or the monstrous Nightmare, hunting Morgan at random and constrained only by time.

The central concern of Prey, of course, is matter. The flagship enemies, mimics, are a great example of this: they can take the shape of anything smaller than themselves in a room, blurring the lines between kinetic and static shapes, organic and material matter. Morgan also straddles this line, in a playthrough-defining battle between human and alien, between development of their natural skills and those of the Typhon. If Morgan invests too much in their alien abilities, the systems of Talos I will turn against them, no longer recognizing them as entirely human (and therefore friendly) – but isn’t that a small price to pay for the ability to hide amongst the mimics, to out-alien the aliens? Morgan becomes a physical intermediary, a gray space between the human interfaces of Talos I and the Typhon parasites that inhabit them, resembling both but accepted by neither.

Morgan navigates that uncertainty by executing their agency in a war of aggressive simplification. The primary creation mechanics of the game are fabricators and recyclers, machines that quite literally create and destroy: recyclers reduce objects to their most basic components (organic, synthetic, mineral, exotic) and fabricators assemble those components into useful items, from bullets to keys to neuromods. An enemy, then, becomes a factory: a dead Phantom might provide a Typhon organ, for example, which can be recycled into a set amount of alien matter, which is a certain percentage of the ingredients necessary to craft a neuromod. A broken hard drive left on an abandoned desk might be the last vestiges of mineral material necessary to create much-needed GLOO. Even alcohol, which provides stat boosts at high costs and is plentiful in the trafficked levels of the game, is valuable when you crunch it into organic material and use that to assemble a medkit. All of these functions are executed by perfect, quiet little cubes. Slotted into the welcoming ports of a fabricator, they overcome the human/alien divide to contribute to a greater whole. Everyone participates equally in the beautiful process of Creation.

Even as Morgan overcomes this difference, though, the Typhon and human crew draw further apart. The humans are constrained by limits of their physical environment; the Typhon, it seems, frighteningly, are not. Ease of access becomes alien. The Typhon are able to control great swaths of humans without a second thought; they close and lock doors, block electricity, and break the complex interlocking systems of Talos I almost on instinct. Humans are confined to increasingly finicky analog interfaces – the safest way across a room might genuinely be shooting a computer screen with a sequence of NERF darts until it unlocks a door that leads the way to safety. Every time Morgan chooses these complicated, inefficient methods of environmental interaction they assert their humanity; every time they blast their way through a level with kinetic energy or take control of an electronic device from far away, they grow closer to the Typhon enemy.

There’s a similarity, here, to the pursuit by current tech companies of eternal simplification. Anyone remember the chaos when Apple removed the headphone jack? The current goal seems to be an absolute lack of friction, a pursuit – often to the detriment of the user – of some perfect, unblemished form. Whether or not that translates to actual, understandable use is often secondary. It often happens that more analog is better for the user – something as simple as volume buttons or a headphone jack, yes, but consider also something like a car, where the carryover instruments of pedals, a wheel and a gearshift are so ubiquitous to make anyone who steps into any vehicle able to carry out the general presets of operation. The current fetish for sleekness actually makes operating modern gadgets harder, with the natural tactile interface sacrificed for a smooth nothingness that requires everything be carefully read.

The question at the heart of Prey is whether Morgan is more human than alien. That’s decided by biology, but it’s also decided by movement and interaction, by the relationship between Morgan and their environment, how they choose to traverse space and play with it. It’s not as simple as friction vs. efficiency, but it does operate within that binary – as Morgan simplifies their world, takes the parts of each element that suits them and builds it into a form that they find pleasing, they say something about themself, and about the material shape of their reality. How they live, how they intend to live, who they are.

———

Maddi Chilton is an internet artifact from St. Louis, Missouri. Follow her on Twitter @allpalaces.