Subjective Analysis of Modern Warfare 2019’s Objectivity in One Scene

So I am not entirely convinced that every single thing in the torture sequence in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2019 is purposefully constructed to avoid the game – and by extension game series, and perhaps by further extension videogames – ever being identified or accused as it were of subjectivity, conviction, stance. This idea I’ve had, that such a scene could be so painstakingly designed to obscure, bely or circumnavigate the potential for an editorial analysis, I’m not sure if this idea is paranoid or simply banks on too grand an estimation of Infinity Ward’s capabilities. It might be that the scene is indeed engineered and thusly contrived to be the fulcrum on which Modern Warfare, and by association Call of Duty’s, evidently lucrative apoliticality can turn. It might be the scene descends, derives, agnates from an encompassing and ambient development mindset, a design philosophy that while not specifically targeted at individual lines of dialogue, is diffused from the top of the creative structure sufficient it ensures that creators and writers on the lower rungs can only think – are perhaps rendered incapable of thoughts otherwise – in apolitical terms. Or it might be innocent, the scene’s profound objectivity solely the product of evincibly low-grade writing, but low-grade writing absent of any form of agenda. For the sake of argument, and given the fetish developers often seem to have, and encourage us to have, for attention to detail – see how accurately the water ripples in the wind – let’s assume everything here is on purpose, and with purpose.

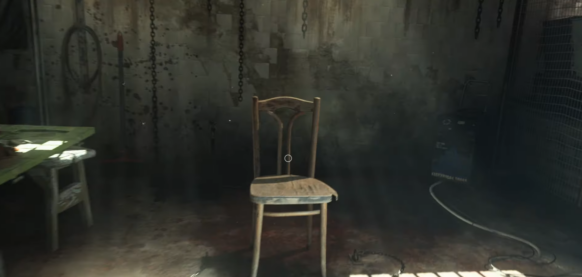

Jamal “The Butcher” Rahar, leader of terrorist organisation Al-Qatala, is tied to chair while a Russian soldier, Yegor, punches him. Rahar planned to release chemical weapons in St. Petersburg but was captured by the British SAS, represented here by Captain Price and player character Kyle Garrick. They want to know who the person that Hadir Karim, Rahar’s Al-Qatala compatriot, is planning to assassinate.

The Butcher provokes Garrick by saying he recognises him – and Price – as belonging to the SAS. Garrick loses his temper: “We need to break this bastard, Captain!” It’s a clever line, insofar as preventing Modern Warfare from sending or receiving, as it were, any real-world implications. Thanks to The Butcher’s goading and Garrick’s emotionally charged response, the situation in front of us becomes personal, an interplay between the competing objectives and spirits of the people in the room, which absorbs, transmutes, simplifies, straightens, equates the broader context that would otherwise, potentially, be dragged into question. It is Garrick, the man, just the man, who wants to torture The Butcher, not the military, government, nation, culture that Garrick might represent.

Price instructs Garrick to collect a “package” that will be instrumental in coercing The Butcher to admission. Here we take control of Garrick and walk him outside the interrogation cell to a van that we open the back door of to find a woman and child of the same brown-skin, implicity Middle-Eastern but otherwise fictional ethnicity as The Butcher – he comes from “Urzikstan”, which the cynical, tired and revert Muslim in me wants to remark, with no small quantity of fucking belligerence, may as well be called like “Jihadistan” or “Nineelevenistan” given the purpose it serves in Modern Warfare’s pretext, i.e., this is where the terrorists come from, but yes, we, as Garrick, force this Urzikstani woman and her son out of the van and start leading her to The Butcher. The mother, Ousa, speaks to the son, Amon, in accented but otherwise flawless English. She does not wear a hijab, which, for the wife of an implied (though the word implied is triply underlined, both in my own affect and on the whiteboard I imagine in any Call of Duty script workshop, which gives the game some defence from the point I’m about to make, though the existence of that defense is circumferentially also my point) Islamic terrorist seems to me unusual – or not so much unusual as contrary to the characterization the game would otherwise want us to believe, the imagery it’d want us to comprehend. Al Qatala, of which The Butcher is leader, is shown perpetrating terrorist attacks on both London and the US Embassy in Urzikstan. Al Qaeda, which means “the foundation” or “the base” whereas Qatala means “killers”, likewise is the perpetrator of terrorist attacks both on London and the US Embassy, albeit in Somalia rather than the country that doesn’t exist. Modern Warfare wants for us to apprehend The Butcher as the leader of Al Qaeda, and but also wants to preclude too Islamic or even specifically ethnic characterization of him, which it achieves through the seeming absence of Islam or ethnicity from his wife. If Inarguable, Ineffable Characterization as Islamic Terrorist with a Fundementalist Islamic Agenda were a physical space, The Butcher would both occupy and and be vacant from it, there and not there. Modern Warfare deploys its sleight of hand thematic, narrative, dialogical magic trick, making us think something we have seen, we haven’t, and in reverse.

Like when Ousa turns to Garrick and tells him “what you’re doing is unforgivable”. A torture scene is about to proceed, and what is happening is still happening, but Modern Warfare provides itself a tactile exoneration and assuagement, surreptitiously, almost subliminally, educating players that it is going to present and later justify the torture of The Butcher, but does not approve of it, but is going to present and justify it, but does not approve of it, and so on. Returning to the interrogation chamber, Price offers Garrick and by extension players a choice – are you in or out? Again, the effect is both dual and manifold, heightening the sense of atrocity and realness – what could be so awful as to make a veteran SAS soldier need to avert his eyes? – while also returning, or rather continuing to confine the subsequent events to the realm of the personal: this is Garrick choosing to do this, not any greater national, political or military power, which remain unblemished owing to the obviousness of his and the players’ agency, a point – this is Garrick, Price and the independently behaving members of their team doing this torture, not on behalf or direction of a country or culture – a point reinstantiated when Price says to Garrick, provided he/the player agree to partake, “you wanted the gloves off? They’re off.” the torture is thusly once again framed as transpiring at the personal discretion of Price et al, disentangling, for example, the country in which Call of Duty is produced, from being answerable to any convictions. But that, again, is only half the genius, as the line “you wanted the gloves off? They’re off” simultaneously implies this depiction of torture, this game, Modern Warfare, is averse completely to compromise, that it’s willing to reveal and cognise, with both its eyes and a full noon sun, what really goes on in the world, a truth so bold and unvarnished you must volunteer, agree a waiver, forfeit notions of fantasy and soul shielding before you can be permitted to absorb it – reality unbound.

The Butcher and his family, as they attempt to calm one another, also speak English between them, again reducing potential of Modern Warfare being aligned against, and by such alignment, for, any ethnicities, nationalities or ideologies of all forms. The characters are neutrally cultured, heralding from a fictional state, which geographical position in relation to others, let alone political or social stances, are left deliberately unknown – they are brown skinned, but either white or indeterminately sounding and behaved, such as an audience might bestow them subjective identity should they choose, but do not have to, should they choose otherwise. Moreover, the interpretations of this sequence, and by extension the whole game Modern Warfare, are provided room to maneuver and dissemble. If for some reason it were auspicious for the makers of Modern Warfare to claim in interview their game broached worldly issues, The Butcher, Ousa and Amon are ethnicized sufficient that such claim could bore honesty and withstand at least superficial inspection. If the opposite, and it were germane the developers de-emphasize Modern Warfare’s leanings or slants, the characters are likewise sufficiently unethnic to allow that route also.

The masterstroke of the whole scene is when Yegor, the Russian interrogator, looks at The Butcher, his wife, his son, and says to Captain Price “Captain, I can’t do this,” and Captain Price replies with “you’re excused”. I mean, the sheer brilliance of this, how it succeeds both in heightening the extremity, severity and realism of the scene – and by association the game – while simultaneously instructing the audience the actions of these soldiers are individual, agentic, unlicensed by the state – the military and the country, whatever country, it may represent, cannot be attributed with blame or guilt or responsibility. This is a personal effort, by persons unbeholden and unswayed by any doctrine or even general, ideological tide. In Yegor’s departure, the whole scene is mitigated safely beyond the point of cohesion. The dis-unification of the torturers – some, like Price and Garrick, are in, others, like Yegor, are out – makes it impossible to identify, or credit Modern Warfare with possessing any single or tenacious conviction. The purpose of this line is not to proffer any sort of morality or purposeful dubiousness – Modern Warfare is not trying to illustrate the point that not all soldiers are the same, or not all soldiers agree with all military methods, and the cultures that sponsor them. The purpose is to deprive Modern Warfare of purpose, to once again belie possibility of locating a concerted meaning or theme or consistency of depiction. The goal is to undermine thought. Whatever you may think about this scene, Modern Warfare, Call of Duty, the example which evidences that thought can be countermanded by an example contrary – Yegor leaves, Modern Warfare is making a stance about the morality and efficacy of torture, but then the torture happens, and the game justifies that to the audience, and so you may think Modern Warfare is again making a point, contrary to the last, about torture’s morality and efficacy, but then you recall Yegor leaving, and the point that seemed to betray, and then you recall how the game later justifies the torture, and so on and so on and so on, with no issue or outcome. The goal is to be incomprehensible, to confound attempts at comprehension such as would cause disrepute to the game and its series.

The act of torture itself is mild, at least mild in comparison to what a player may reasonably expected all the build up and melodrama to presage, as Garrick points a pistol at The Butcher’s family, pulls the trigger to reveal it’s empty, loads it with bullets and threatens to pull the trigger again, at which moment The Butcher confesses. No one is physically harmed. It’s finished in under a minute. But torture of a description did take place. Modern Warfare can be described, as it describes itself, as depicting torture, and thus accumulate reputation, gravitas, credibility for being in artistic terms uncompromising and real – the game does depict torture, so if for whatever reason it were auspicious to claim Modern Warfare takes an unwavering look at the brutalities of its eponymous subject, such a claim could be evidenced. But if it were contrarily auspicious to position, characterize, market Modern Warfare as entertainment, a fun shooter, not-too-heavy, the relative lightness of the scene – relative to anyone who has seen torture’s depiction in, for example, Zero Dark Thirty, from which the game borrows heavily in its nighttime raid sequences, or the newspapers, like for instance during the Abu Ghraib scandal – then Modern Warfare could be positioned, characterized, marketed that way, also. Controversy, or controversialness, is again a physical space Modern Warfare both does and does not occupy, can either inhabit or exit as circumstance may demand – the game can be sold to people who want something potentially “hard-hitting”, but also sold to people desiring the opposite.

And the scene concludes with a voiceover from Price: “There is a fine line between right and wrong.” No further judgment follows. The torture is not designated as either right or wrong. Modern Warfare simply acknowledges the existence of a moral dubiousness. And again, the purpose here is not to offer a statement, an answer, a position of any type, but propagate further equivalence. Truth resolves from fact. Fact, naturally, attends ambiguity and duality – or more – of perspective. And this becomes the ultimate and most exquisitely designed trick of Modern Warfare, whereby its contradicting, self undermining representation of, in this case, torture, creates an illusion of fairness, the way that it seems to present “both sides” – yes, soldiers torture, but not all are comfortable with it; yes the direct recipients of torture may be terrorists, but they are not the only victims, and the methods are unsound – allows the game to be, again, credited with an almost journalistic integrity, an honest balance. But behind journalistic and balanced accounts typically likes the ambition to edify, illuminate and provide – even if it is discrepant and dis-harmonized, a truth, a tangible, communicable truth. Even if it makes you conflicted, and only more acutely aware of the convolution and multifariousness of something, a true account will still leave you with that solid thought, that solid feeling – “I know that this subject is not straightforward.” This does not feel to be the objective of Modern Warfare, which permutes, modulates and attentuates – sabotages – each of its successive images, thematic presentations and dramatic moments not to present a complex but discernibly complex truth, but instead to nullify truth, make truth inaccessible, impossible. The goal is to look like something and be nothing. But to look like something. But be nothing. But to look like something.

———

Edward Smith is a writer from the UK who co-edits Bullet Points Monthly.