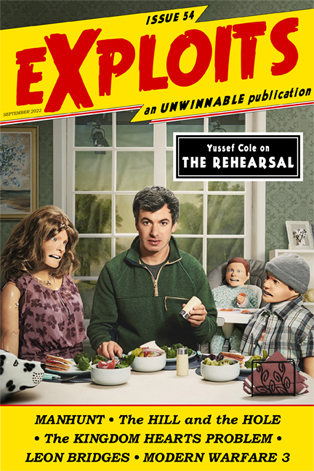

The Rehearsal

This is a reprint of the Television essay from Issue #54 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

This is a reprint of the Television essay from Issue #54 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

———

At the end of the first episode of The Rehearsal, a show ostensibly about Nathan Fielder helping random strangers rehearse difficult future encounters in controlled environments, he chooses to withhold a crucial piece of information from his subject, Kor Skeet: that the trivia game he’d been rehearsing for had been spoiled ahead of time, all the answers already leaked to him surreptitiously. While rehearsing to tell his friend that he’d been lying about his academic credentials, Kor inadvertently wound up participating in an even bigger lie. This becomes a fundamental takeaway for the show. That the idea that we can control our lives is fake. All the money in HBO’s coffers can’t buy authenticity or realness. In trying to control your life, you wind up creating fiction.

The show’s finale is the ultimate doubling down on this concept. The season-long rehearsal that Nathan had been running, in which he attempts to help a single middle-aged woman named Angela practice the act of raising a child, has finally unraveled. Angela is gone and Nathan has taken over, becoming his own final subject. He claims he’s interested in exploring his own parental ability but the experiment has had so many recursive twists by this point that whatever the original goal may have been is now utterly lost.

Instead, the final episode focuses on one of the child actors who played his and Angela’s fictional son Adam, a six-year-old named Remy. Here Nathan does what has made The Rehearsal (and his previous show, Nathan for You) so endlessly compelling: he finds the kernel of reality that has come loose from all the artifice. He turns the camera onto a child who has been forced to participate in Hollywood’s churn of soulless exploitation, and who is legitimately suffering. This suffering comes from Remy playing the role of son to Nathan’s dad when he himself does not have one. His real pain at losing Nathan once the show ends stands in sharp contrast to the extreme artificiality of the rest of The Rehearsal’s framing. Naturally, Nathan descends like a vampire; mines it for content, and forces us to watch. He takes the real and weaves it into fascinating fiction.

The show ends on this uncomfortable note. The “real” Nathan plainly poking through his hastily constructed caricature of Remy’s single mom. He breaks character, with his “scene partner,” another, slightly older, child actor and asserts himself as, well, himself. “Aren’t you supposed to be my mom?” “No, I’m your Dad.” But, after six episodes of five-dimensional fakery, how can we even be sure he means it? How can we be sure he would know it if he did?