Rehearsal

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #154. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

What’s left when we’ve moved on.

———

“This network of times which approached one another, forked, broke off, or were unaware of each other for centuries, embraces all possibilities of time . . . In the present one, which a favorable fate has granted me, you have arrived at my house; in another, while crossing the garden, you found me dead; in still another, I utter these same words, but I am a mistake, a ghost.” – Borges, The Garden of Forking Paths

In early July, I went to see the Whitney’s Biennial exhibit Quiet As It’s Kept. The exhibit is announced on the ground floor by a series of flags with proclamations I can’t remember stitched on in bright colors. The exhibit takes up two floors of the five-floor museum. The exhibit is nominally about the coronavirus. The curatorial statement reads:

We began planning this Biennial in late 2019: before Covid and its reeling effects, before the uprisings demanding racial justice, before the widespread questioning of institutions and their structures, before the 2020 presidential election. Although underlying conditions are not new, their overlap, their intensity, and their sheer ubiquity created a context in which past, present, and future folded into one another.

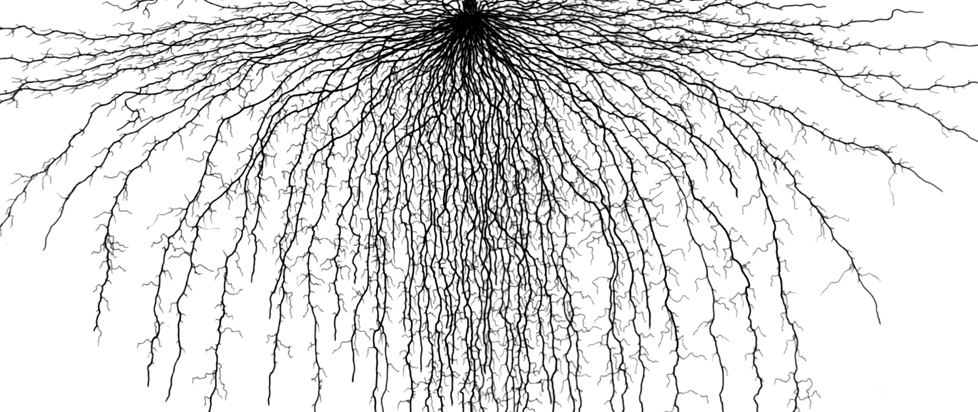

The exhibition is labyrinthine on purpose. The top floor, the one I visited first, is dark and contains several video pieces nestled around in hallways. There was a sculpture made of glass and plastic that clung to the ceiling, in the form of a neural network. The pathways lit up every few seconds, which the plaque said had something to do with the levels of carbon dioxide in a particular place. Again, I’ve forgotten the details. You could lie down on a couch below the network and watch the lights flash, but the couches were crowded, and anyway I didn’t want to look at it anymore.

After about an hour, I left without seeing the rest. I found the exhibit disorienting. It was odd to step back out into the 5pm sunshine and feel the clamminess and unrest dissolve. It did what it was supposed to do, at least I think it did; I was disturbed, provoked and interested. Time was flowing a little differently.

This week, I’ve been watching the new Nathan Fielder show The Rehearsal. In the first episode, Nathan meets a man named Kor from Brooklyn who goes to trivia every week at a bar called the Alligator Lounge. Kor has been lying to his friends for years about having an advanced degree, and now he’s ready to come clean; in order to help him do so, Nathan builds an exact replica of the bar in a warehouse, implants trivia answers into his brain over the course of weeks and drives him through rehearsals of the same conversation over and over.

The show has been called manipulative, sociopathic and dangerous by people on the internet. All of these are obviously exaggerations and misnomers. I’m more receptive to the opinion that Nathan is a demonic genius, or an alien sent to school people on social norms and how to break them, or just a dorky guy touched by the power of prophecy. But both of these opinions miss how the show is actually trying to paint him: not as an analytical genius, but as a deeply anxious person struggling with being unable to control what’s going on. One conversation that shows this is at the end of episode one, when he is apologizing to the actor he hired to play Kor for deceiving him and ruining his streak of not cheating at trivia. Nathan (or what constitutes Nathan’s character) can’t actually have the real conversation: he can only bring himself to apologize to his subject’s shadow.

By the time this column goes up, the whole season will have been released, but I’ve only watched the first three episodes. What I’ve seen so far reminds me so much of How To With John Wilson, which similarly dramatizes its host’s interactions with other people doing crazy things, and was produced by Fielder. The Rehearsal, though, is more focused on the mechanics of conversation. The second episode, which is about a woman named Angela practicing raising a child from birth to teenagerhood in eighteen months, involves her going on a series of dates that reveal the scaffolding underlying those constructed interactions (and also the eels guy).

Apart from the obvious comedy, it’s compelling to watch people relive conversations over and over, return to the same missteps and mistakes, and try to gain a sense of certainty that it’s impossible to ever actually get. Even in the final performance, the opportunity for mistakes is present, an issue which the participants themselves seem to frequently find sad. As Nathan says about the reconstructed bar in the first episode, “It was the only place where failure was impossible”.

The Rehearsal made me think a lot about how we approach social failure, and how much it’s possible to invest in trying not to fail. Structurally, it creates the closest thing to an unalterable scenario it’s possible to make: constructed environments with a reality TV budget behind them, and an all-knowing figure encouraging people to run it again. There’s not just a darkness, but a sadness behind that imperative: both Nathan and his guests are so determined for things to go right, and so scared that they won’t, and the more they invest in the former, the more the latter gets to them. The final conversations are haunted by their previous mistakes, so that even when things go smoothly, there’s a clear sense of how exactly they could have gone wrong. Every time Nathan runs a conversation differently, he creates an alternate universe where his subject’s life plays out differently, and then rewinds to try it again.

At least on the surface, this repetition can be uncomfortable, even perverse. This is why, even though it’s billed as a comedy, The Rehearsal made me profoundly and strangely sad. That’s not to say I don’t like it. It is to say that it gives me a sense that I’m watching something private, a negotiation between two people who desperately want the situation they’re practicing to come under their control, and will do almost anything to get it there. In one scene at the end of episode two, Nathan calls the parents of child actors to ask them to let their children participate in the parenthood experiment. He reads his answers off a flow chart that looks like the back end of a Twine game: if yes, proceed to response x; if no, proceed to y. It makes cause and effect visible and maps out all the disparate ways each choice can cascade out into a multitude of other choices. Change one variable and you could end up lying to a stranger about your grandmother or talking about wireless radiation levels in rural Oregon.

Mark Amerika’s GRAMMATRON (once exhibited, as it turns out, at the Whitney) is widely considered one of the earliest digital versions of hypertext fiction, works that incorporate branching paths and reader/user choice. Textual versions include Julio Cortazar’s work and (debatably) Ulysses. Hypertext fiction, at least on its face, tries to share control of the text with the reader. It wants to at least give the illusion that the story you’re reading is one you’re helping to tell, or shaping your own experience of more than you could otherwise do.

GRAMMATRON describes itself as taking place in “a near-future world where stories are no longer conceived for book production but are instead created for a more immersive networked-narrative environment that, taking place on the Net, calls into question how a narrative is composed, published and distributed in the age of digital dissemination.” It takes the viewer through a shifting landscape of vaporware aesthetics that provide an intentional overstimulation, in line with Amerika’s interest in the artist’s struggle to remain coherent in the wake of internet advertising (“the mindless techno-spam of invasive technocapitalism”).

The Rehearsal isn’t hypertext fiction. It’s a surrealist reality show that’s at least partly scripted and is predetermined, without divergent user experiences. Importantly, it refuses to share control: we can’t rewind and choose again. This is partly a limit of the medium, but partly also revealing of the kind of show this is: a mostly controlled experience about the experience of lacking, and wanting, control, and the fantasy of having the resources to achieve it.

The end of the show’s third episode gestures directly at this artificiality. The child actor for Nathan and Angela’s three-year-old is replaced with a six year old. Stagehands in headlamps bury store-bought vegetables in the dirt at night while Nathan’s voiceover explains that this appearance of accelerated domesticity is necessary to pretend that the experiment is normal life: “Nature’s timeline has to be accelerated, and your brain desperately tries to adapt to your new reality.”

The Rehearsal might actually be anti-hypertextual: it provides you with one or two conversational branches, leaving you to guess how else it could have gone, but giving you only one answer. However, like hypertext fiction, it is interested in overloading the viewer with options they can’t pursue, whether because they have made their own choice already or because directorial control means there is no choice to be made. If GRAMMATRON is about an oversaturation of internet marketing blocking out the possibility for art, The Rehearsal is about an oversaturation of outcomes blocking out one’s ability to make any step or construct any form of progress. It shows the inertia that considering all your options causes you to fall into, by giving the subjects – and, through limited repetition, the viewers – the illusion that all their questions will be answered, all their contingencies attended to. It’s a promise: you will be prepared. Ultimately, it’s a promise that can’t be kept.

We began planning this Biennial in late 2019.

Because we don’t live in an alternate reality, I can look up at a plastic replica of a brain and see all the deposits of CO2 in an active area and the way they change over the course of a minute, an hour, or a day. If I stay long enough, maybe I can even find a pattern. But it’s tempting to think there’s a world where the brain is not there, and where the exhibit hall is full of light.

Past, present, and future folded into one another.

———

Emily Price is a freelance writer and PhD candidate in literature based in Brooklyn, NY.