France

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #135. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #135. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Globetrotting through media.

———

Salut! Welcome to this month’s World Tour, grab some escargots, some wine and let’s get started!

Lofofora

This one is less of a deep analysis (because my French is bad) and more of a quick recommendation, but Lofofora is a fantastic and fundamental French rap metal band. They’ve been going for over thirty years at this point and pretty much all of their extensive discography slaps. Their songs come with powerful repudiations of war, fascism and a wide variety of social issues in France. Also have you ever seen a band with a cooler name?

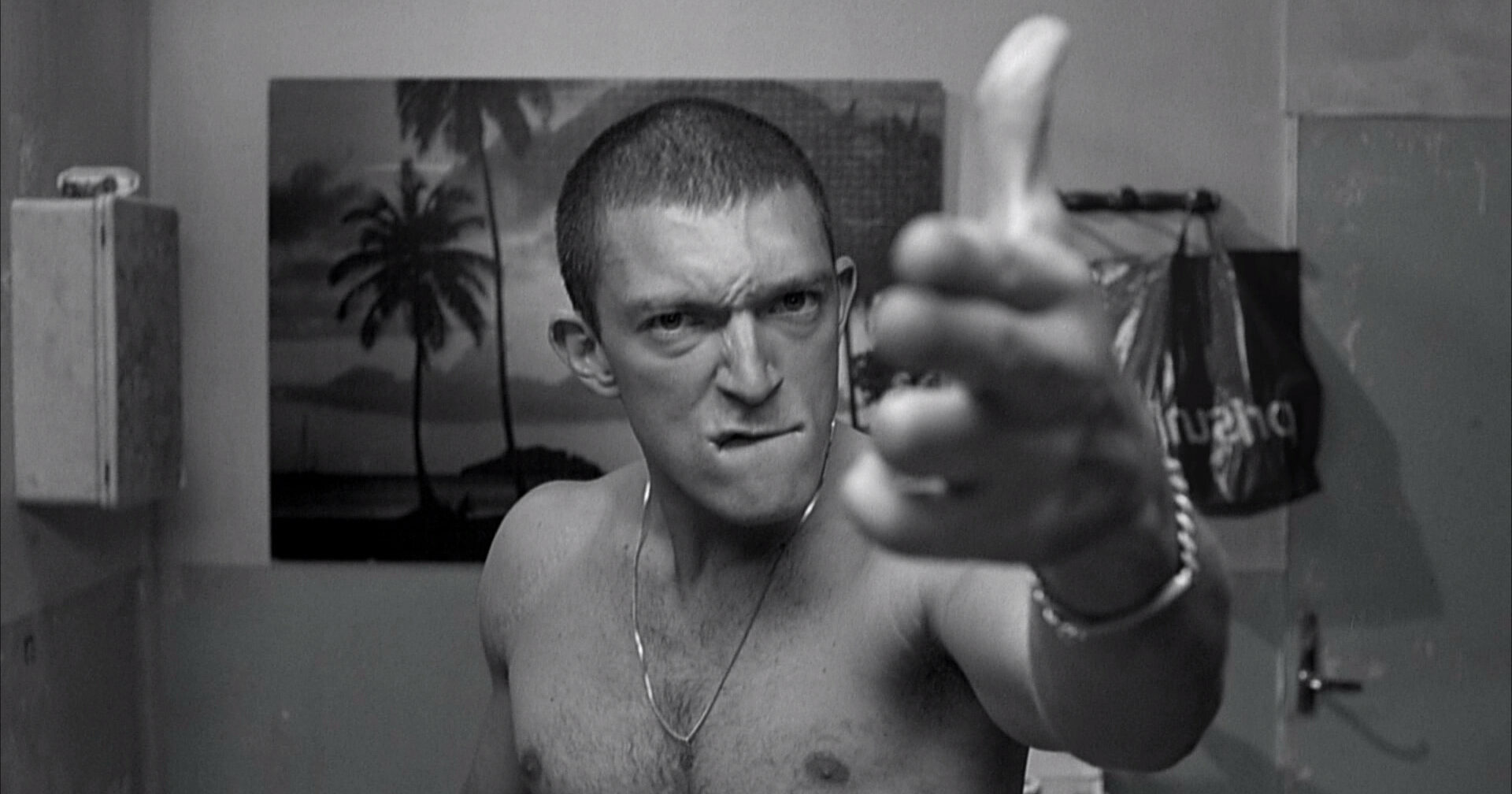

La Haine

This is a film about cycles of violence.

In La Haine we follow three young men in the deprived banlieues (suburbs) for the 24 hours after an uprising (aka riot) caused by police brutality. The immediately interesting thing here in Matthew Kassovitz’s film is that all three of our protagonists are marginalized on the basis of their ethnicity, Vinz (Vincent Cassel) is Jewish, Hubert (Hubert Koundé) is Black and Said (Said Taghmaoui) is Arab. While this isn’t the totality of their characters, it massively informs how they interact with the world. You are seeing France through the lens of the people it seeks to oppress and erase. Kassovitz also doesn’t flatten the racial dynamics here into one singular narrative, instead, the varied oppressions are a key part of what informs their differences. The starkest example of this is Vinz’s volatility in opposition to Hubert’s constant calm. It is never explicitly said, but you can see how Hubert is constantly trying to push against the vision of Black people (especially Black men) as violent beasts, which you can see in the repeated references to him as a Herculean figure. By contrast, Vinz is under no such restriction, his marginalization comes elsewhere and, if anything, he is constantly trying to prove his masculinity through the performance of violence.

This is a film about cycles of violence.

In La Haine we open on a montage of footage from modern uprisings in France to the sound of Bob Marley’s “Burnin’ and Lootin.’” Then we shift to the aftermath of the most recent uprising in the banlieue of our protagonists. There are burned-out vehicles, smashed windows and a car that inexplicably turns up in the wrecked gym. These aren’t the priority though, and we very quickly come to accept them as part of the normality of this place, instead we’re focused on the community that forms here. It’s a mishmash of different people who have been pushed to the bottom of French society. Many of them have mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, children in the prison system and are just about struggling to get by. This place isn’t solely defined by violence though. Kassovitz is sure to show us some beautifully shot scenes of kids playing, impromptu breakdancing and a barbecue on the rooftop. He takes his time to make sure we know that this is a community which exists outside of the violence that runs through it.

This is a film about cycles of violence.

In La Haine we see a lot of interpersonal violence. Playfighting, real fighting, rioting, police violence, vandalism, torture. There’s even a moment where Hubert gives a cop a phenomenal sucker punch. Violence is frequently the medium by which men can express their emotions, whether that’s love, hatred, or a cry of frustration at their material conditions. Most of it is clearly just young men being boisterous rather than anything particularly callous. All of this feels reflective of a model of Western masculinity in which men (especially racialized men) can only express their emotions through violence. So you watch scenes where you wish these characters would just slow down and talk, but instead things spiral in increasingly frustrating ways – and that feels deliberate.

This is a film about cycles of violence – and they start with a police gun

The descent into violence which the film takes is kicked off by a cop losing his gun at the riot which precedes the events of La Haine. It’s the acquisition of that gun which drives Vinz into taking increasingly reckless actions and gives his seething (and largely justified) rage a lethal edge. At pretty much every point in this film where violence becomes lethal (or at least brutal) the power of an oppressive system or structure is involved. The violence comes in cycles, but it is always clear that these structures get the wheel spinning.

Nowhere is this clearer than the actions of the police. They hound our central trio wherever they go, holding their monopoly on violence over the heads of everyone in the banlieue and using that power liberally. There’s an immediate tension whenever they appear on screen which is all to familiar for those of us who are frequently their targets. It’s like the joy and vibrancy of the neighborhood immediately stops. Everything becomes oppositional. A barbecue becomes a standoff. Even just walking with friends becomes anxiety inducing, dominated by the need not look ‘suspicious’, to not give them an excuse (as if they needed one).

You see this at its most cruel when Hubert and Said are taken into police custody and tortured by a trio of policemen. This scene is intense, but also has a grotesque psychosexuality to it. There is a clear and perverse enjoyment of using these systems of power to brutalize this pair of young, racialized men, to reinforce the hierarchy where the police as agents of the state stand on the backs of Black, Brown and working-class people. When the trio are later attacked by neo-fascists, a similar tone persists. They also attack to support the same hierarchy, in which working class people of color will always be at the bottom. In fact, the actions of the neo-fascists and police are near indistinguishable and that is a reality which has existed for as long as the police have. You can see this in the how the groups cross over in membership. It’s also clear in how in France, alongside most of the West, the police are completely unwilling to do anything about fascists – even when they are clearly identifiable. That’s what makes the violence so terrifying here. It isn’t that the perpetrators uniquely talented or organized – it’s that you know that even the liberal institutions of the State will turn a blind eye. The victims will just be another notch in the millions of marginalized bodies these countries are built upon.

It’s also important here to talk about the violences here which aren’t as overt. As mentioned before, so many of the people in the banlieue have been in prison or have immediate relatives who are. Furthermore, these areas are consistently underinvested in and overpoliced by the French government. They create the conditions from which crime necessarily emerges, but instead of improving those conditions, the state incarcerates those who are struggling to survive. The reality of carceralism is that is leaves gaping holes in communities and intensifies the struggle of both the convict and the people they left behind. Improving things isn’t the point. Just like the police, and just like the fascists, this is another method of violence through which hierarchy is asserted. As put by Said in the film he “feels like an ant lost in intergalactic space” – asserting that feeling of powerlessness is precisely the purpose of these systems.

In spite of the overwhelming nature of these oppressions, there is hope to be found. When we situate the origin point for this cycle in the police gun (as a representative of the racist, carceral capitalist state) then we know that none of this is natural. The titular hatred has a starting point – so we can cut it off at the source.

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, podcaster and general procrastinator from London. You can find their ramblings @naijap-rince21 and their poetry @tayowrites.