The Misogyny Industry

It took me five days to watch all of Star 80, Bob Fosse’s 1983 fictionalization of the grooming and murder of Dorothy Stratten by her husband Paul Snider. It is absolutely grueling—not just the murder but in depicting the entire process of Snider entrapping and attempting to control Stratten.

The details of Dorothy Stratten’s life are the details of her murder. She didn’t have a chance to live. That’s the reality of it. The way Fosse communicates this is by constantly and mercilessly cutting between the chronological telling of the story and the scene of the murder. From the very beginning there is no pretense that this was a “relationship” in anything but the most academic sense. Dorothy Stratten is 18 years old and working at a soft-serve shop when Snider sees her and immediately focuses his attention on her—as opposed to the girl he came there with. Stratten is put off. Snider sets off alarm bells in her head. He’s transparently sleazy and aggressive.

But he is persistent. Persistent men are like battering rams; given enough time it’s likely they will smash whatever obstacle is in front of them. Snider has all kinds of outsized ambitions. He wants to make Stratten a star, which he had tried with other women previously. He takes her to her high school prom, which is horrifying. He nudges her into nude photography. She’s good at it—she has presence, her personality comes across on camera. That she indeed becomes a star is her own achievement.

I say that there’s no pretense that this was a relationship, but I guess that does not scan the same way for everyone who watches Star 80. In Adam Nayman’s review at Reverse Shot he says Fosse’s flash-forward device is an obvious juxtaposition of “eros and thanatos” and in fact “more purient” than telling the story in a more straightforward fashion*. Far be it from me to start beef with a seven-year-old review but this seems tremendously misguided. We are never allowed to forget that “eros” didn’t factor into this situation at all—Snider saw a girl he thought could mold and dominate until she made him enough money for him to get rid of her. This is a movie about a predator. Snider, in his myopia, never anticipated that she could do anything without him, without his “management.”

He wouldn’t be alone. If you think Star 80’s linkage of Snider’s micro-level misogyny and the misogynistic industry of Hugh Hefner’s Playboy empire are in any way reductive, I’d point you toward how both Stratten’s murder and this film were covered at the time. Vincent Canby, writing for the New York Times, makes a dubious crack about Stratten’s achievement not quite equaling “Madame Curie’s” and concludes “[t]he story of Dorothy Stratten is pathetic, but only another Playboy model might find it tragic.” (That one could, as they say, use some unpacking.) Teresa Carpenter’s “Death of a Playmate,” the Village Voice article on which Star 80 is in part based, accumulates a slight callousness toward Stratten and a type of sympathy for Snider’s inability to hang with the Hollywood elite, as though a more savvy slimeball wouldn’t have killed her. Which is maybe true—a more savvy slimeball made her a Playmate.

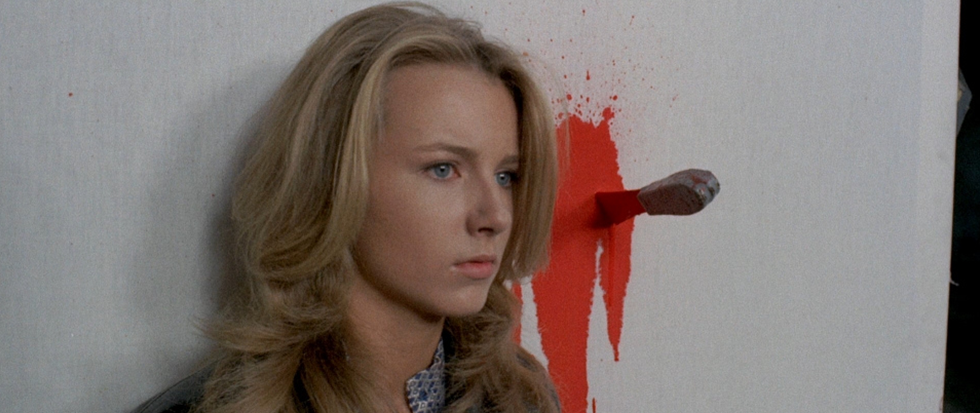

Mariel Hemingway constructs a version of Dorothy Stratten who is effortlessly charming, self-effacing, and sweet. Star 80 does not pretend to be any kind of biopic; in fact, it is more about unpacking Snider’s persona rather trying to give a full portrait of Stratten as a person. Hemingway invests the character with such life under those conditions, a vitality that is precisely calculated. Eric Roberts’s sniveling, grotesque performance as Paul Snider reveals his pathetic scheming for what it really is. Stratten’s utter lack of guile shows Snider to be delusional simply by contrast; he simply hates women and wants to destroy them. Her behavior is inconsequential to that; she, as a person, is inconsequential.

The darkest irony of Dorothy Stratten’s death is that what was done to her by Paul Snider links them forever. She got away from him; she had won. But in death she is bound to her murderer by the final exertion of his violent will. Fosse’s film collapses grooming, control, abuse, and death into a single state—a brutal and uncommonly straightforward** depiction of totalizing misogyny.

//

*This reminds me of the complaint that Jack Nicholson is too obviously unhinged at the start of The Shining, which is of course the point—he’s an abusive husband and father before he ever steps foot in the hotel. But I suppose there are some people out there for whom 90% of cis men’s actions don’t scan as alarming and inappropriate.

**I feel like most movies about grooming are difficult to even describe as being about grooming because they don’t get it themselves—think of An Education or Call Me By Your Name.