Never Be Clean Again

Describing a Kiyoshi Kurosawa movie is difficult. At least for me! If description is the primary task of the film critic—and I would hardly be the first person to say that it is—then Kurosawa’s movies offer her a unique challenge because they are often defined by absence. I just watched Cure (1997), and I promise I’ll get to discussing it, but I want to talk about Kurosawa and Japanese horror first.

Any broad auteurist assessment of Kurosawa’s work, like that of Takashi Miike or Andrzej Zulawski, can’t help but reduce his polyvalent career to that of a stereotypical genre stylist, or a “J-horror” director long past his prime. The releases of Kurosawa’s Cure and Pulse (2001) coincided with that profitable uptick in Western interest in Japanese horror movies and, in particular, remaking them for US audiences. The Japanese originals were packaged and discussed as a discrete wave rather than filmmakers directing genre movies as they had always done. At a glance it’s not difficult to see why the lean structure of Ringu (1998) sparked foreign remake interest where, say, Shozin Fukui and Shinya Tsukamoto’s oddball 90s films didn’t. Home video labels like Tartan Asia Extreme and Unearthed Films were (often still are) the only way to access most these films in the US, which meant Western viewers couldn’t avoid the accompanying narrative*.

Takashige Ichise, producer of Noroi: The Curse (2005), the original Ju-On films, Dark Water (2002), and the US The Grudge (2004) among others, fanned the flames of early-2000s Japanese horror to the extent that he commissioned the six-film J-Horror Theater series. Starting with Infection (2004), only three of the films officially came out under that banner, though all were eventually produced—the sixth was finally released in 2010. Ichise didn’t somehow tarnish the authenticity of early-00s Japanese horror, not with the flurry of sequels and remakes in the cash-cow Ring and Ju-On franchises from 2000-03, but his role in commodifying the idea of J-horror was of course influential on how these films are discussed by Western critics.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa has definitely gotten his critical due at this point, I think—your Reverse Shot/Film Comment types love him, even if his later work is dinged more than the 00s run. Personally I was nervous to watch Cure because I love Pulse so much. I saw Pulse at an impressionable age, so the actual movie might be immaterial compared to its formative impact. Cure is even more hollowed-out than Pulse; it is not about the apocalypse, necessarily, but it feels equally apocalyptic. That brings us back to the idea of absence.

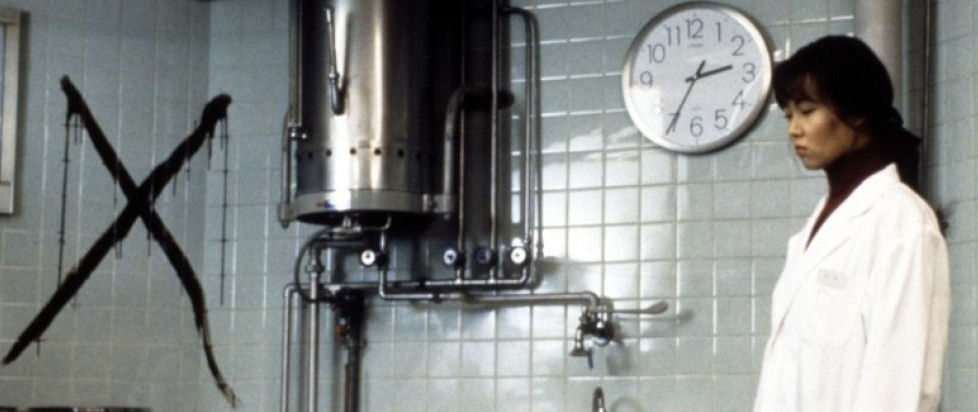

If absence identifies a Kurosawa horror movie, how, as a critic and a filmmaker, do you describe absence? Kurosawa chooses to emphasize the space around characters; cavernous, abandoned industrial buildings like those in Pulse swallow the frame. Office buildings, city streets, family homes, even cars and buses are marked by a reverberating visual emptiness. The important characters in a given scene are often the only people in the frame, but in Seance (2000) and Cure, supernatural/unexplainable happenings manifest in crowded public places that nonetheless may as well be empty—no one sees unless they’re meant to. There is seemingly a void in these movies where the usual structures of society are intended to make meaning; people act in erratic and unexplained ways and apparitions exact revenge from the living for wrongs done long ago, but apathy reigns over everything.

As one of the last horror movies Kurosawa’s made to date, Loft (2005) is a slight outlier—a self-described riff on Japanese horror tropes that frequently, and unusually for Kurosawa at the time, jump cuts between handheld footage and static shots. It seems to deliberately unbalance his established style in search of something new, but many of its exterior shots, with characters wandering through dense, beautifully lush forests and hanging around a ghostly abandoned pier, have his signature emptiness even if the plot and narrative are particularly knotty.

Also of note is its use of overt CG effects, which echo the ending of Pulse as well as Kurosawa’s recurring use of rear projection, in their blatant artificiality. No attempt is made to reconcile the digital with the indexical reality of the image; another way of putting this is that the effects are “bad” in a lazy film critic sense: “bad” meaning you can tell they aren’t real (that’s because they aren’t, eagle eye), and “aren’t real” meaning you can tell someone created them**. Penance, Kurosawa’s 5-part 2012 miniseries for Japan’s WOWOW, is shot on digital. This affords a kind of disquieting hyperrealism; extreme clarity of motion and careful color grading turn bland-beyond-bland modernist domestic-urban spaces into chambers of the uncanny. I’ve rarely seen interiors on film that look as bizarrely sparse and unyielding as those in the first episode of Penance.

I should also point out that no matter who Kurosawa’s sound designers are, his mastery of sound is a constant. In Cure, he drops the audio completely out when the amnesiac drifter Mamiya hypnotizes someone. Single sounds, ones with clear diegetic origin points like a glass tipping over, puncture the silence. One scene in Pulse, one of the most terrifying things ever filmed in THIS girl’s opinion, has the word “tasukete” (help me) repeating on the soundtrack and literally nothing else—to the point where you can hear the audio crackle fade up as the word is spoken. The voice of the ghost in Retribution (2006) is uncomfortably close-miked and airless. The scene in Seance of a ghost appearing in a restaurant tamps down the sound to reflect the protagonist’s horrified fixation. This absence of ambient and foley sound is strategic; Kurosawa always seems to be aware of how much noise the viewer is hearing. His sound design is subjective and expressive, yes, but also thoughtful in a rare way.

Cure is about Mamiya coming into contact with people. He talks to them, drawing out their anxieties, their long-held frustrations, their unspeakable desires. A cop who hates his partner; a doctor who loves cutting into male corpses. He hypnotizes them with the flick of a lighter, or by spilling water. Then they—not he—kill someone and carve a bloody “X” into their throat.

His relationship with the detective Takabe is different. Takabe is not hypnotized, at least not overtly. Instead he is drawn to Mamiya because he thinks Mamiya has done something to him; he just doesn’t know what. He hallucinates and loses sleep. His relationship with his wife deteriorates even further. The obvious metaphor is that of a moth to the flame: an unnamable, annihilatory attraction. Mamiya plants himself in Takabe’s head like a splinter, slowly becoming inflamed.

By the end of Cure the world seems to be collapsing. The rage bubbling beneath seemingly everyone in Tokyo begins to leak out. Perhaps inevitably, Takabe becomes the next Mamiya—a carrier, of sorts, a person whose presence affects the material world around him. In the end, as Mamiya infected Takabe so Takabe infects those around him, without even saying a word. “Mesmerism” was originally meant as a cure. In a certain light, what Mamiya does, opening people’s inhibitions to the desires within them, is its own sort of misanthropic cure. After all, it’s what’s in their hearts that drives them to kill.

Reading Cure as a kind of ironic take on psychiatry, though, is too facile to suffice. An easy reading doesn’t fill all that emptiness. The disjunction between the murderers’ desires and their public personae is not subtext; it’s overtly explored in dialogue. The notion that Mamiya is offering a way out of society is similar to the rhetoric of the Aum Shinrikyo cult*** whose 1995 gas attacks on the Tokyo subway haunt Cure. It is a movie about belief systems; the ways in which they wind around every aspect of someone’s life and shape everything they see before they can interpret it for themselves. Mamiya’s way out is only another sales pitch, the human meat-grinder of capitalism shrunk to miniature. You want something? Go get it. Fuck whoever’s in your way.

//

*The whole “J-horror thing” is more than I can fully discuss in this column, though I’ve tried to offer a gloss. Other people have done it better than I can anyhow—Midnight Eye and the old Snowblood Apple site were hugely influential to me. These films deserve better than “Wacky Japan, Huh?” and Quentin Tarantino endorsements, which in many quarters remains all they get.

**See Evan Calder Williams’s brilliant Shard Cinema for more on this topic.

***See Haruki Murakami’s Underground.