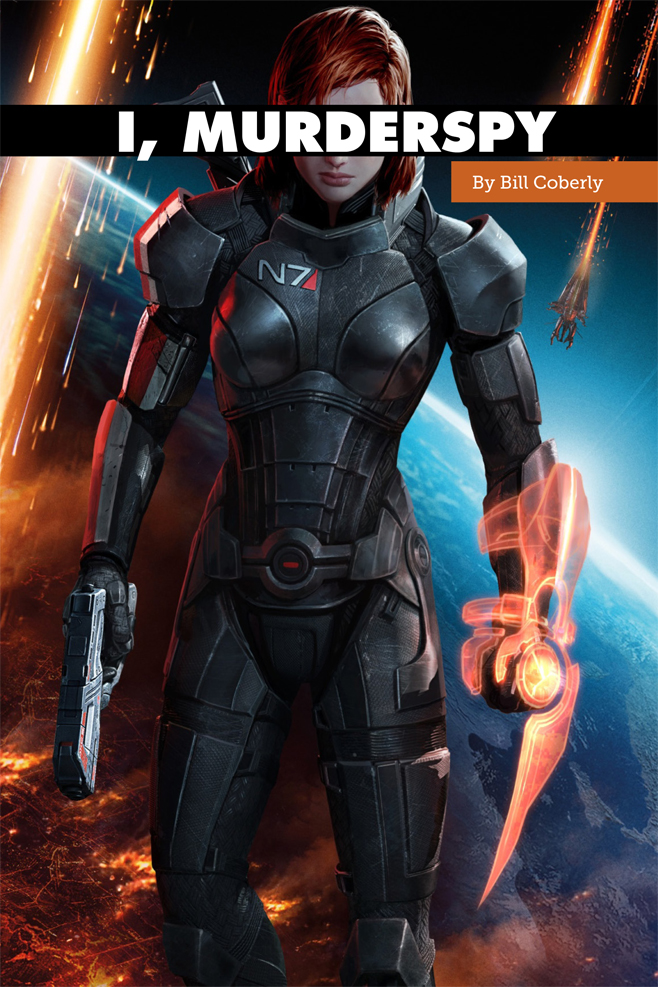

I, Murderspy – An Excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly 96

This feature is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #96. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

The first Mass Effect sure thinks the solution to complicated galacto-political problems is the deployment of unaccountable government murderspies.

The Citadel Council, an interspecies space-UN that governs most of the galaxy, has access to its own military police force (Citadel Security, or C-Sec,) and can usually expect to command the militaries of its various member species. But when it needs to perform complex operations that require a finer touch, it turns to the SPECTRE program and the men and women within it. SPECTREs (short, hilariously, for SPECial Tactics and Reconnaissance) have almost complete authority to do as they please, and are generally considered to be above the law.

Developers working on the Mass Effect franchise have described the first game as being about “becoming the first human SPECTRE.” The player character, Commander Shepard, is a soldier and war hero who has been chosen by both human and alien leaders to become the first human to join the ranks of Council SPECTREs. In the fiction of Mass Effect, humanity has only recently joined the galactic scene and the first game begins only 27 years after humanity first encountered aliens. Thus, for a human to join the Council’s Secret Murderspy Police is treated by the game as a momentous occasion, marked by considerable political discussion and fanfare by the folks back on Earth. The player gains this status after the game’s prologue, and the plot of the rest of the game is shaped by the privileges and responsibilities of SPECTRE-hood. Shepard is granted access to secret places, given interviews by important people, and allowed to make outrageous decisions, all because of her SPECTRE status.

Developers working on the Mass Effect franchise have described the first game as being about “becoming the first human SPECTRE.” The player character, Commander Shepard, is a soldier and war hero who has been chosen by both human and alien leaders to become the first human to join the ranks of Council SPECTREs. In the fiction of Mass Effect, humanity has only recently joined the galactic scene and the first game begins only 27 years after humanity first encountered aliens. Thus, for a human to join the Council’s Secret Murderspy Police is treated by the game as a momentous occasion, marked by considerable political discussion and fanfare by the folks back on Earth. The player gains this status after the game’s prologue, and the plot of the rest of the game is shaped by the privileges and responsibilities of SPECTRE-hood. Shepard is granted access to secret places, given interviews by important people, and allowed to make outrageous decisions, all because of her SPECTRE status.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Shepard’s interactions with the Council are fraught from the very beginning. The Council is skeptical of the very concept of a human SPECTRE, and Shepard’s insistence on talking about godlike robots coming to Kill Us All rankles them. (The plot of the first three Mass Effect games revolves around an inbound armada of Lovecraftian robot squids, the Reapers, that harvest all life in the galaxy every 50,000 years). But what’s curious is that the game gives the player relatively few opportunities to try to mend this relationship or remain diplomatic with the Council. Despite Mass Effect’s much-vaunted dialogue system, which purports to give the player a multitude of ways to respond in a conversation, there are frequently no options in which Shepard treats the Council with deference or much in the way of tact. Early in the game, when Shepard is still trying to convince the Council of the threat of the Reapers, the most polite response to one Councilor’s doubts reads “I tried to warn you about [the badguy] and you refused to face the truth. Don’t make the same mistake again,” which is not what I would call a diplomatic tack to take with one’s boss.

But even when the game gives the player the opportunity to be polite to the Council, it always dangles the temptation to do something rash under their nose. After each major mission, the player has the opportunity to call the Council and report what happened. At least one member of the Council is always grouchy with Shepard’s performance and choices (whatever they were), and Shepard can immediately either hang up on them or ignore their criticisms. The game wants you to fight with the Council, and it consistently frames Shepard and the Council as adversaries. Shepard, however is never wrong, and the bureaucrats in the Council are never right. If the Council would simply believe Shepard and get out of her way, she could have saved the galaxy much sooner and with much less loss of life.

[pullquote]Mass Effect is . . . escapist fantasy, committed to making the player feel important, respected, and, above all, powerful.[/pullquote]

This is a common trope in genre fiction generally: the badass cop or starship captain who is continually hampered by the red tape and the sniveling bureaucrats in the office. If only these heroes could escape all those pesky rules, and that ridiculous need for oversight, they could protect us so much more efficiently. But in Mass Effect’s case, this trope is made even more pronounced by its place in a choice-driven RPG. These games have an almost pathological need to fawn over the player and their choices. For all that Mass Effect is a relatively mature science fiction universe, it’s also escapist fantasy, committed to making the player feel important, respected, and, above all, powerful.

The reason for the SPECTRE’s supra-legal status thus has less to do with the setting or creating an interesting plot, and more to do with the fact that Mass Effect is a videogame. Choice-driven RPGs like Mass Effect want to give their players different ways to approach the scenarios they present. Is it better to storm the front gate or sneak in through the sewers? Should you bribe the bouncer, knock him out, or charm him into letting you into the club? Baldur’s Gate wanted to give players the option to be good or evil, Knights of the Old Republic lets the player character succumb to the Dark Side of the Force, and Mass Effect wants to let the player choose “Paragon” or “Renegade” approaches to difficult situations. (Roughly, “ends don’t justify the means” and “sure they do,” respectively.) If the game slapped the player on the wrist every time they chose a “Renegade” option, it would diminish that radical freedom which games like Mass Effect purport to offer. Although half the fun of playing a game like Mass Effect is seeing the consequences of your actions throughout the franchise, these consequences always play out in the lives of other people. Shepard remains a war hero and the savior of the galaxy, no matter how many rules she breaks.

———

Bill Coberly is a lawyer and occasional writer-of-things who lives in Minneapolis, MN, with his wife, Erin, and two small and snuggly terriers, Azathoth and Nyarlathotep. Follow him on Twitter @BillCoberly.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 96.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!