Long Live Emulators

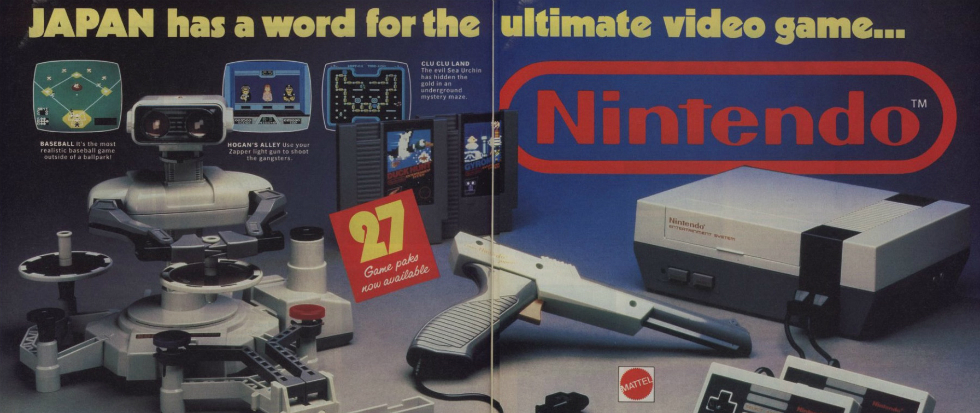

The “New” Nintendo Entertainment System is an emulator in a mini NES shaped box. There’s not much more to it than that. It’s a very well packaged and branded version of something that is free (but somewhat illegal) on the internet today. But for this reason it’s an important stopgap in the ever increasing problem of videogames archiving, research, and preservation.

Think back to the oldest console you still own. Mine is an Atari 2600, but I have no way to connect that Atari to any of the TVs in my home. Though adapters exist, it’s not inconceivable that by the 2600’s 50th birthday in 2026 there won’t be any way to plug those systems into contemporary TVs at all.

Then there’s the problem of the machine itself. Most of these early machines are far beyond their intended operating lifespans. That any of them continue to work today is a testament to the brilliance of their designers and manufacturers. But older consoles break, many of them irreparably, and so too do their peripherals. What happens when the last one breaks?

That’s why the NES Classic Edition is a stopgap, and a blessing, but not a full solution. Though it makes older games, which have become difficult to play on contemporary TVs, available to a wide audience it still relies on current video standards. Technology has a habit of always being in transition. How long before a successor to HDMI rears its head? How long until that successor gives way?

This is where emulators come into play.

If you wanted to play an older game but don’t have, or don’t have access to, the system, it’s easy to dig up an emulator and run whatever you want on your computer. This is the power of emulators, simulations which mimic the original software environment of older games. A quick search can reveal archives exist with over 40,000 games available for 50 different systems. However, emulators exist in a legal grey area. Depending on your country, and if you own an original copy a game, you may run afoul of international copyright law.

Legal considerations aside, the digital nature of videogames makes them somewhat easier to archive and preserve. Unlike books, film or art, huge amounts of physical space aren’t required. Preservation techniques for digital media already exist as server backups and cloud storage. And since emulators can be designed to run in web browsers, no additional technology is required to access the games.

This isn’t without its drawbacks. Emulators are often played without the original controllers. Sometimes sound and art assets can only be approximated and the experience as a whole is fundamentally different than playing an original cartridge and controller. Emulators are only as good as their name, they emulate games and systems but they aren’t those games or systems. These data stores aren’t perfect either. Because of their digital nature entire decades of games can be wiped out in an instant if something happens to a server.

For this reason, emulators too are only a part of the solution. They’re the eBook version of what can be found at brick and mortar institutions like the Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment and the Strong Museum of Play. While such museums lack the ease of access of emulators their value is in authenticity, originality, and the truest form of preservation. They preserve and archive videogames, their consoles and peripherals, and as many original documents as they can get their hands on.

Going forward, the primary questions are still the same. How do we preserve games? Will the Nintendos, Sonys, and Microsofts keep rehashing their back catalogs with updated connectors? Will companies/scholars/historians/average folks embrace aftermarket emulators as the primary source of games from yesteryear? Or will we come across more garage sale tug of wars where dashing, young archeologists demand that old consoles belong in a museum and wealthy collectors seek to keep them for themselves?