It Never Ends

Today I’d like to explore videogames, creation and bittersweet parting. Before I do that, though, it’s important that I pause for a moment to talk to you about fedoras.

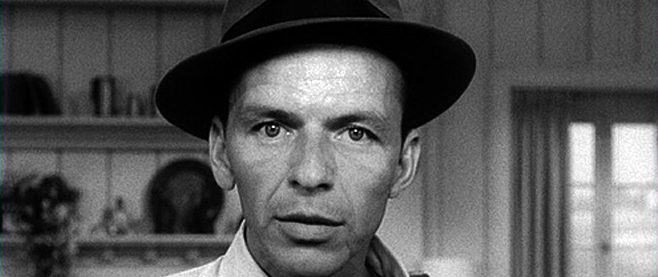

I love fedoras, but I do not own a single one. This probably comes from the great respect I hold for Frank Sinatra, one of my idols. I’m not quite certain what I mean by saying this, but being the Frank Sinatra of game design is kind of what I’m going for. Actually, that’s a lie. I know exactly what I mean, but explaining it would take a while, and we’re talking about hats here. That guy could really wear a fedora, far better than I could hope to. Besides, most restaurants and bars where I live in Los Angeles don’t have hat hooks anymore.

[pullquote][I]t is at the end of an experience … that we take the longest pause to consider what we’ve accomplished and what will come next.[/pullquote]

But Stu Horvath wears the hell out of a fedora. I met Stu and his merry band of Team Unwinnable writers during last year’s GDC. He told me all about their website and introduced me to game writer aces like Gus Mastrapa and Chris Dahlen. Between their uncanny grasp of the art of journalism, and Stu’s fedora finesse, I was hopelessly hooked on Unwinnable.

Unwinnable became one of my most well-worn bookmarks as I finished my master’s degree in game design at USC’s Interactive Media Division. A couple of months before I gave my closing thesis defense, I cofounded a game studio called Rad Dragon, with the aim of exploring new avenues of game narrative by making the flavor of crunchy fun games we love. Whilst exploring these avenues, I decided to begin discussing my most burning game design thoughts in a public, blog-like format. Stu saw my Twitter hand-waving about this and approached me about contributing to Unwinnable from a game designer’s point of view. I was incredibly humbled, thrilled and terrified by this idea. I couldn’t presume to keep up with brilliant wordsmiths like Stu, Gus, Chris and Jenn Frank – actual professional writers.

I could, however, use fancy French literary terms! I’d been mulling over the topic of denouement in game stories for some time. Denouement plays a critical role in classic storytelling structure. After the story has built up its energy to a climax of maximum emotional gravity, a gradual plot denouement (literally, “unknotting”) allows the audience to purge these emotions and return to a healthy baseline, hopefully walking away from the tale with a catharsis and slightly new perspective on the world. There are some fascinating cases of what this means in the interactive medium of videogames.

Earthbound, a beloved JRPG for the Super Nintendo, lets you experience the resolution in your own time. After its climactic battle, it plops you back into the game to explore the world you just saved. Every character has something new to say now that the danger has passed, and you have time to appreciate the impact you’ve had on these 16-bit people. The game only gives you the proper credit-roll ending after you’ve returned home and gone to bed. It’s a wonderfully satisfying conclusion to a long and often punishing game. Ico and the more recent Red Dead Redemption address denouement in their own unique ways that I won’t spoil here, but I will say that each carefully honors the emotional journey it has taken its players through, and escorts them back to reality with an elegantly-matched piece of denouement.

This topic is so ripe for discussion amongst developers and players who care about storytelling. The indie movement has ushered in a growing collection of unique narrative games of shorter length, meaning that more players will get to the end of our stories – we hope. Ironically, as I prepared to leap into the ranks of Unwinnable’s elite team, armed with my rich subject, it hit me:

This topic is so ripe for discussion amongst developers and players who care about storytelling. The indie movement has ushered in a growing collection of unique narrative games of shorter length, meaning that more players will get to the end of our stories – we hope. Ironically, as I prepared to leap into the ranks of Unwinnable’s elite team, armed with my rich subject, it hit me:

I’ve never made a game that ends.

I’ve been designing games professionally for about five years and as a hobby for longer. And while I’m so fascinated by game endings, somehow every game I’ve been a part of creating has been the type that has no absolute finish.

I worked at Disney for a couple of years, game designing and scripting for MMO games like Pirates of the Caribbean Online, but MMOs by definition do not end. They allow their players to grind forever, living perpetually in an open world. Some MMO teams have both the misfortune and creative opportunity to kill their game worlds when the decision is made to shut down the game’s servers, but I haven’t been a part of such an event.

I’ve made a lot of small games and prototypes over the years, too, but they’ve always been too small to warrant some form of ending sequence. The closest I’ve come is The Moonlighters, a game I showed last year at E3, but that’s sitting in fundraising limbo. Most recently, Rad Dragon released our first iOS game, Shove Pro, but that’s a variation on the Endless Runner genre of mobile games. There it is, right there: “endless.”

Shove Pro’s loop follows a typical mobile game tradition. You play; you get coins; you use coins to unlock new modes, cities, outfits, etc; you keep playing. The economy caps by around Level 50, meaning if you’ve reached Level 50, you’ve probably unlocked everything the game has to offer.

As of this moment, the highest level Shove Pro player is at Level 141, nearly three times our soft level cap. I feel simultaneously pleased and wistful about this. On one hand, somewhere out there is a person who loved our game so much that she just kept going, even when we had nothing left to offer her beyond the core mechanic in the way of shiny objects or crazy cheat modes as a reward for her efforts. That is a heart-warming thought, really.

But on the other hand, I’ll never get to say goodbye. One day she, like all our players out there, will stop tapping the icon to shove on her way to school or work or a tennis match. She’ll find amusement elsewhere. She’ll look back fondly, I like to think, at her time spent with the game, but like that TV show I just stopped watching after a lackluster Season 2, our game will never give her closure. Let’s imagine her life’s entertainment consumption transmogrified into the form of a picnic basket, as one often does. I would want Shove Pro to appear as a delicious chocolate chip scone, but instead it’s this melty wheel of cheese that will go great on crackers for a little while, but that no one’s really going to polish off. Also, they couldn’t possibly, because it’s a never-ending cheese wheel.

Adam Saltsman gave a moving talk at the 2011 IndieCade Conference in which he talked about respecting our players’ precious time that they willingly entrust to us. Life is finite, and time is so valuable. When we game creators invite players into our worlds, our systems, we ask for their trust that the time spent will not be wasted. That doesn’t mean that all games must provide some tangible benefit to players, but it does make me think that it would be beneficial to all parties if I could give our players that additional dimension of comfort:

“Trust me, and I will give you a valuable experience, in the proper amount of time.”

There’s nothing wrong with games that don’t end, mind you – with letting a player decide when she is done playing for good. I am terrifically proud of Shove Pro and grateful to all our players. It’s fun and hilarious and fresh and you should try it (PLUGGING!). But as a creator, I like the notion of delivering a conclusion to my players. “There it is. That’s the game I made for you. You’ve seen it all! Go do something else after you’ve taken a moment to digest this.” As they say, all good things must come to an end. I want to design that end and bid each player a bittersweet farewell, like Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca. Like Scarlett Johansson and Bill Murray in Lost in Translation, we’ll go our separate ways having grown from knowing each other.

There’s nothing wrong with games that don’t end, mind you – with letting a player decide when she is done playing for good. I am terrifically proud of Shove Pro and grateful to all our players. It’s fun and hilarious and fresh and you should try it (PLUGGING!). But as a creator, I like the notion of delivering a conclusion to my players. “There it is. That’s the game I made for you. You’ve seen it all! Go do something else after you’ve taken a moment to digest this.” As they say, all good things must come to an end. I want to design that end and bid each player a bittersweet farewell, like Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca. Like Scarlett Johansson and Bill Murray in Lost in Translation, we’ll go our separate ways having grown from knowing each other.

Though we aren’t announcing Rad Dragon’s next game for a month or two, I can say that it will have an ending. We’re still figuring out how to greet each player at the beginning, but I’m already sharply attuned to the fact that I’ll finally have the opportunity to craft a denouement. The more I consider it, the more I feel the gravity of this task, because it is at the end of an experience – whether it be a game, a calendar year, a relationship or whatever – that we take the longest pause to consider what we’ve accomplished and what will come next.

So here I am, saying goodbye to you for now. I hope I’ve accomplished something on this page, and that you’ll stay with me for the next piece I’ll be fortunate to soon write for you here at Unwinnable. I promise you more windows into my game creation exploits, and probably more discussion on the rich, rich topic of fedoras.