Liminality: Fear of Transition

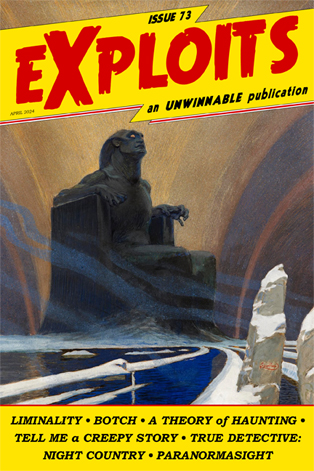

This is a reprint of the feature essay from Issue #73 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

This is a reprint of the feature essay from Issue #73 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

———

To call something “liminal” is to suggest it’s in transition – between a before and an after. Like the pandemic that accelerated its popularity, liminal aesthetics have faded from the forefront of internet consciousness, but haven’t gone away. They remain a favorite trope for communicating the uncanny, the unsettling and the horrifying, and it’s easy to understand why. Transitory spaces are restless and anticipatory; something must come before, something must come after. To be forced to dwell in the liminal can be extremely disquieting. It’s a terrifying suggestion that someone might call a transitory space home.

I am nonbinary. This isn’t reflected on my government documents, nor is it known by distant friends and family. Forgotten internet accounts resurface with disturbing regularity bearing old names. I’m in the process of changing.

My presentation is traditionally masculine, but decreasingly so. I am between man and other: I am liminal. It’s uneasy to be between. To never quite find certainty in a traditionally defined identity – neither one nor the other. Transition is rarely recognized as a state of being. There is before and there is after. Male to female. Female to male. Cis to trans.

So where does that leave me?

I may be liminal, but that doesn’t rob me of identity. In any context, for any subject, there is always a before and after. We needn’t always be understood by who we were and who we’re becoming. We are no less ourselves when in transition.

I long for alternative depictions of the liminal, beyond the simple aesthetics of horror. CosmoD turns transient spaces into vibrant loci of life in his exploration of train stations, streets and clubs. His game The Norwood Suite fills the halls of a hotel with people, their dreams, motivations and secrets. The game’s soundtrack integrates reactively into the building itself. All the hotel’s inhabitants, no matter how permanent or ephemeral, are connected by its music. Liminality is used to explore the strange ways people are connected, and the life that thrives in places defined by inevitable departure.

Yume Nikki takes place in a girl’s uncanny dreams. Her waking hours are limited to a sparse room and balcony, but her dream world is expansive, labyrinthine and diverse, containing items called “effects” that allow her to change her appearance and identity. Her liminal dreams are often unsettling, but offer the freedom for self-exploration that is absent in the real world.

The animated short film Goodnight, Sweet Dreams! Pajama Mammal·Saur by Lychenthropy similarly explores dreams, using them for respite from a confusing, anxious reality. The surreal, half-remembered dreamscapes offer quietude otherwise unavailable in quotidian life.

I enjoy liminal horror, but there can be so much more to liminality. There has to be. Transition can be overwhelming, and I’d rather not spend it perpetually anxious – there’s no need to fear transition. Yes, it can be scary. It can be uncertain. But it can also be a place of sojourn, beauty and identity.

I am liminal. And I think I’m going to be okay.