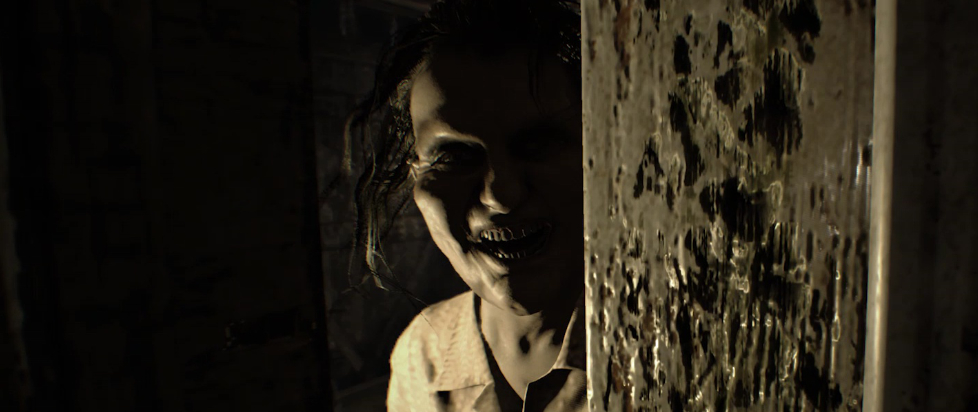

RE7 as American Folk Horror

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #167. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

We are what we’re afraid of.

———

Thanks, perhaps, to the success of Midsommar in 2019, folk horror is having a minute in the scholarly study of horror. From edited collections on the topic to a truly awesome three-hour documentary on the genre, it seems like lots of folks right now are interested in what qualifies as folk horror, and how we can describe its particular experience. On first glance, folk horror seems almost handcuffed to British and European horror traditions – often relying on idyllic agricultural landscapes and superstitious salt of the earth peasants, the kind of which you see relatively little here in America. But in recent years, our ideas of what constitutes the genre have expanded, to include more contemporary horror aesthetics and to think more broadly about what constitutes folklore.

I, personally, really enjoy this trend and like to think about folk horror expansively, as anything dealing with folklore and myth – Candyman, for example, is definitely urban folk horror. Slenderman from my column last month also makes a case for itself as being folk horror. To truly understand this, though, we have to think a little bit about the themes of folk horror, and how they can be built upon to reflect our modern way of life. To do so, I’ve selected what I think is an excellent example of modern videogame folk horror: Resident Evil 7: Biohazard.

Warning: this is gonna get a little bit into arguments like “is x a metroidvania?” because I firmly believe that genre boundaries are permeable and that things can be many things without adhering strictly to every rule of those things. As long as you don’t wring your hands over essential definitions, I think we’ll be cool.

So, it seems to me that folk horror relies on three things, fundamentally, for its particular approach to being scary. First of all, obviously, there must be some sort of mythos or folktale attached to the narrative, likely providing the origin of the monster/evil. For this example, I’m taking a relatively broad view of myth here, and thinking about the legacy of lore and worldbuilding from decades of prior Resident Evil content, that much of the audience is intimately familiar with. Teasing out the mythos of the Resident Evil franchise is far too big a task for a column of this size, so I’ll simply say that the game rests on a mountain of near-folkoric knowledge. Additionally, the game relies heavily on another kind of mythos – stereotypical ideas about Southerners. The game is rife with imagery of a once-prosperous family, the Bakers, brought low into poverty and squalor by their backwards ideas (and exposure to biochemical weaponry). As someone who did not live in the deep south when I first played this game, but who has now lived here for going on three years, the developers are definitely playing into how more urban Americans think of the South and the people who live there for a lot of the horror.

The second thing that seems to be really important about folk horror is that the aesthetic of the piece relies in important ways on nature – most of the action probably takes place in a remote rural area, such as an island or, in the case of RE7, an isolated piece of swampland in coastal Louisiana. The use of the bayou as a location for the game has many connotations for Americans, from unrealistic notions of voodoo to slightly geographically incorrect Deliverance references, but it definitely, I think, lends to the (folk) horror of the situation. Resident Evil as a series has seen many different locales, but this one speaks most clearly to nature as a facet of horror.

The third thing is that in folk horror, the bad guy most often ends up being us – people. Man is the real monster in the Anthropocene. It is our interference in the natural order that brings about the monstrosities, and RE7 is no exception, with the biochemical shenanigans of the Umbrella Corp being the ultimate cause of the corruption of the Baker estate and its inhabitants. Folk horror thus acts as a cautionary tale – do not meddle in things beyond your ken. Playing God, or acting in God’s name, is a surefire way to get yourself turned into a goopy swamp monster, along with several other innocent people.

I think I’ve made here a pretty solid case for Resident Evil 7 to be considered a solid entry in the folk horror canon. I think this is pretty important as a consideration of the franchise, because it expands and elevates the way we think about the horror game experience. Folk horror has been previously siloed largely into highbrow or arthouse horror forms, cult classics and such. By opening the doors of videogames to horror subgenres beyond “zombie shooter,” and “jump scare horror,” we can come to understand more about horror, more about the game, and more about why these experiences unsettle us.

———

Dr. Emma Kostopolus is an Assistant Professor of English at Valdosta State University. Online, you can find her nowhere, but check out her film reviews for Ghouls Magazine and her recent article for Computers and Composition Online. She’s also the co-author of Ace Detective, a murder mystery dating sim you can play at oneshotjournal.com.